Point 'Em Out is an editorial series where Blavity Arts writer Ida Harris explores the latest and the greatest in Black art. Thanks to modern-day technology, we get to be virtual consumers of yesterday's icons and today’s most innovative Black artwork, and — if we're lucky — the Black geniuses who produce them.

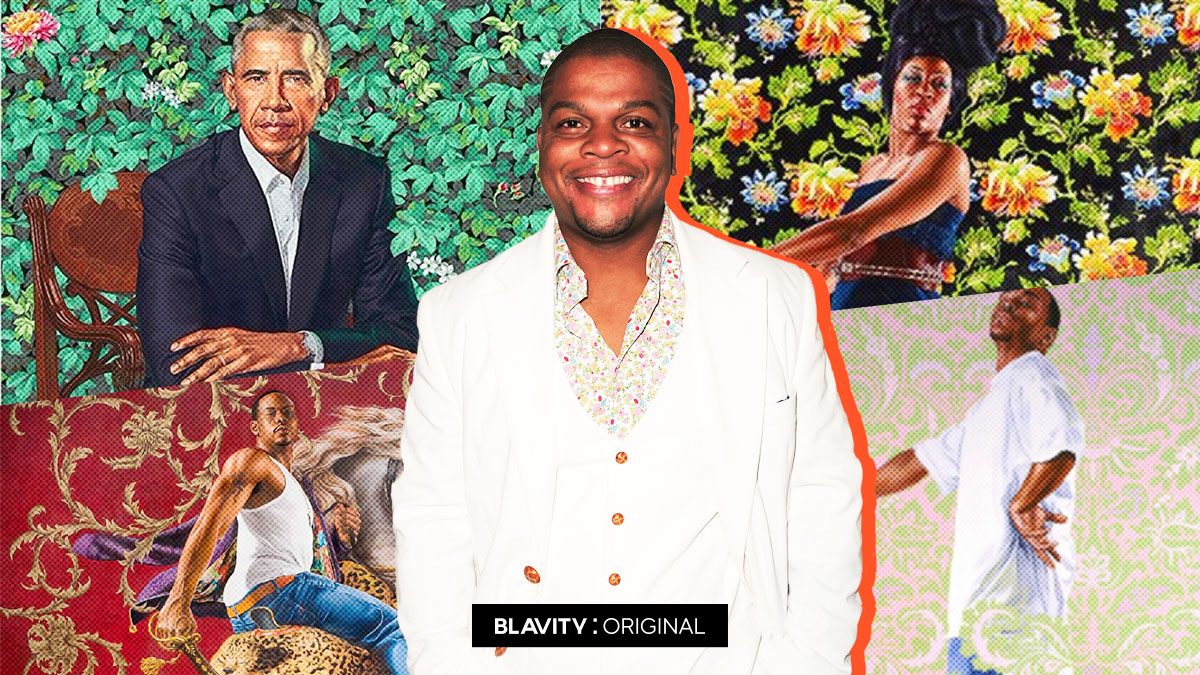

Kehinde Wiley is a creative savant hailing from South-Central Los Angeles, who easily fits the "genius" descriptor. His artistic brilliance cannot be denied, nor is it anything to sneeze at. He is the creative hand behind Barack Obama's presidential portrait. In 2018, Wiley immortalized the 44th commander in chief in an 84 x 57-inch painting that captured Obama's excellency, legacy and personage against a vibrant backdrop of chrysanthemums sprinkled with jasmine and African blue lilies, signifying the former president's roots in Chicago, Hawaii and Kenya.

Though Wiley's fame has catapulted since creating the Obama portrait, his name has been ringing bells in art circles for a long time, with quality work driving their reverberation. After graduating from Yale with a bachelors of fine art, the West Coast artist cut his chops in Harlem, New York, humanizing Black men by way of the canvas. From Michael Jackson to everyday n****s, Wiley's content highlights the opulent regality of Black men. His paintings often position the common dude outfitted in his urban threads in stately battle and equestrian poses in the likeness of European visual narratives via large-scale paintings.

The painter has also shaken s**t up with art pieces depicting Black women with knives and the severed heads of white women.

“It’s sort of a play on the ‘kill whitey’ thing,” Wiley said, speaking of the paintings in a 2012 interview with New York Magazine.

@benshapiro @andrewklavan Given your interests in the culture this might be an interesting topic. Kehinde Wiley has appropriated feminist interpretations of Judith and Holofernes. Feminists see the story as anti-patriarchy. Kehinde shows white people decapitated instead. pic.twitter.com/WinQNKkNLu— #1 Marmaduke Fan (@No1MarmadukeFan) February 12, 2018

In an effort to not only amplify other creatives, but also shift the global narrative and perspective of Africa, Wiley created Black Rock Senegal, an artist residency in Dakar that "seeks to support new artistic creation by promoting conversations and collaborations that are multigenerational, cross-cultural, international, and cross-disciplinary."

Mastery and art-ivism such as Wiley's could never go unrecognized. The Gordon Parks Foundation honored the charismatic artist this year for his philanthropy and humanitarianism in the arts at their annual awards dinner and auction. Between graciously meeting and greeting attendees and accepting his accolades, Wiley allowed Blavity to get up in his business.

Blavity: As a Gordon Parks honoree, you are certainly carrying the flag. What does a moment like this mean for you?

Kehinde Wiley: This moment means it's the coming together of Gordon's vision. Gordon's vision was to see America — warts and all — to be able to add light through a lens so we can see Blackness. And he's inspired so many young artists, and he's an artist on whose shoulders I stand. To be able to be honored here tonight represents the coming together, the closing of a circle. I feel truly honored by that.

Blavity: How has painting the Obama portrait impacted your life?

Wiley: It's changed the whole game. People don't have to ask "who is that guy?" any longer. It's given me a recognition that has opened doors now. It's allowed me to take certain risks with my work; to be able to sort of blast past the notoriety of the Obama portrait, which is quite impossible, but it is certainly the air beneath the wings and we all need that.

Blavity: You were at Art Basel 2012, and I remember people asking, "Who is that?" I'm glad we know exactly who you are today.

Let's talk Black Rock Senegal. What was the impetus for the initiative?

Wiley: The impetus for Black Rock was to make Africa the global center for creative thought, and return it back to its rightful place as the focal point where artists see themselves and the world. Africa has been seen through the lens of disaster for so long that I felt it was necessary to be able to create a corrective space.

Blavity: Awesome. And who is it for? Why Senegal, as opposed to Compton or Brooklyn?

Wiley: Many African Americans have a real strong need to have a connection to the source. To be able to work in Africa has been a long dream, not only because my father was born in Africa and he and my mother broke up before I was born, but because, like many African Americans, there's a desire — there's an urge within me to be able to see it myself outside of what I've been spoon-fed through television and media. To be able to meet with young artists and feel a state of grace and becoming, shoulder-to-shoulder with my brothers and sisters on the continent.

Wiley has navigated and dominated the art game for some time, establishing himself as a consummate art professional with critical work that gave Black people shine. He has cemented himself on the distinguished walls of national history with a bold, Black-Black portrait of America's first African-American president, and added to the creative canon that's emerged from the African diaspora while encouraging others to do the same.

Although Kehinde Wiley has done plenty, it's clear he's only just begun.