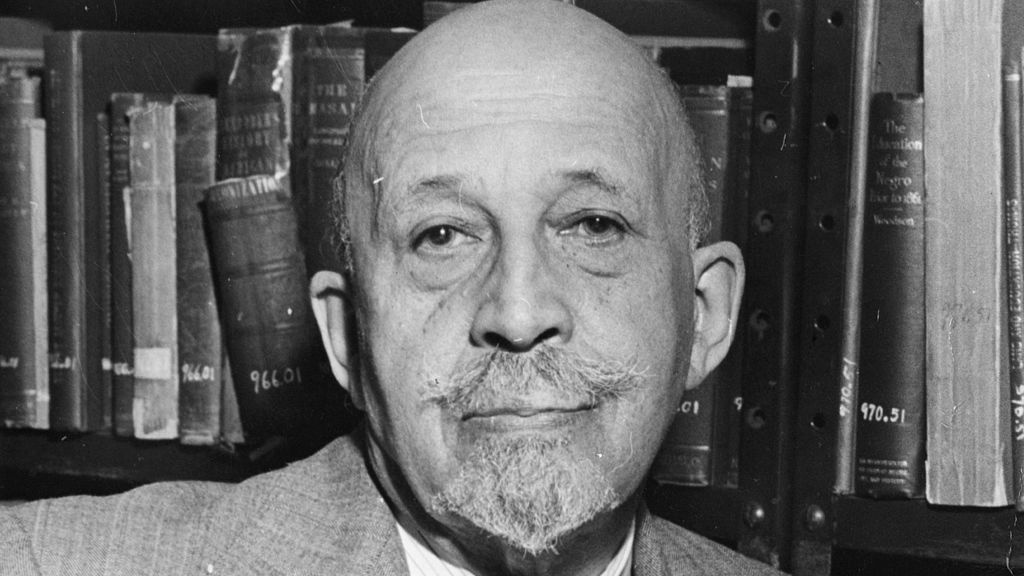

Few people have had as large an impact on Black America as W.E.B. Du Bois.

Known as the scholar and activist who revolutionized the field of sociology, Du Bois also co-founded the NAACP and led the Pan-African Movement that promoted solidarity between Black leaders and people throughout the diaspora. He is often remembered for his achievements, as well as his differences with Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University).

Though Du Bois publicly disagreed with the head of one of the nation’s premier Black schools, this does not mean that he overlooked the value of HBCUs. On the contrary, Du Bois was a product of an HBCU education, a faculty member of a Black university for much of his career and a lifelong proponent of Black-led education.

Here's what you should know about how he shaped — and was shaped by — HBCUs.

1. Du Bois connected with Black culture through his HBCU education

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Growing up in a majority-white New England town and attending integrated schools during his childhood, he gained new exposure to the Black community when he traveled south to attend Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Du Bois was happy to enroll in Fisk, although his “family and colored friends rather resented the idea” of him relocating to the segregated South, as he later recounted.

Du Bois thrived academically and socially at Fisk. It's also where he honed the skills that he would use throughout his career as he became a skilled orator and editor of the school newspaper. He also taught rural Black students in Tennessee during the summers. But it was also during his time at Fisk that he witnessed firsthand the southern racism and discrimination that he would fight for the rest of his long life. Years before developing his Talented Tenth idea, then-college student Du Bois wrote home, “I can hardly realize they are all my people; that this great assembly of youth and intelligence are representatives of a race which twenty years ago was in bondage.”

By contrast, when Du Bois graduated from Fisk and made it to Harvard, he said he felt like an outsider at the Ivy League school. He later recounted that he “was in Harvard but not of it.” Harvard would not honor Du Bois’ degree from Fisk, making him earn a second bachelor’s degree before subsequently gaining a master's and a doctorate. After becoming the first Black person to earn a doctorate from Harvard, Du Bois is alleged to have said, “the honor, I assure you, was Harvard’s.”

2. Du Bois made Atlanta University a pioneer in the field of sociology

Although often remembered for his activism, W.E.B. Du Bois was also one of the United States’ most important academics, helping to establish the field of sociology in America. Although racism prevented Du Bois from being hired by any of the major white universities, he was invited to join the faculty of Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta). Du Bois was a faculty member at Atlanta University from 1887 to 1910, leaving to establish the NAACP, and returning to the university from 1934-1944. At Atlanta University, Du Bois was a prolific scholar, producing numerous groundbreaking works including his masterpiece The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

He also built up the school’s fledgling sociology department into one of the nation’s strongest programs, attracting top-notch students as well as prominent faculty. He led the effort to conduct sociology using scientific, data-driven techniques. Dubois was, in the words of scholar Aldon Morris, “the first number-crunching, surveying, interviewing, participant-observing and field-working sociologist in America,” and he instilled those techniques in his students at Atlanta.

3. Du Bois connected with future world leaders through HBCUs

Throughout his career, Du Bois was an advocate of Black education, Black political rights and Black liberation at home and abroad, seeing these missions as interconnected. He consistently promoted Black colleges and urged them to provide students with extensive liberal arts education, in contrast to the vocational-based education promoted by Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee. Du Bois also connected the political rights of Black Americans to the cause of home rule and eventually decolonization in Africa, as expressed in his speech “To the Nations of the World” delivered at the first Pan African Congress in 1900.

Du Bois’ scholarship and activism attracted national and international attention. One of the people drawn to Du Bois was Nnamdi Benjamin Azikiwe, the future first president of Nigeria who was a student and then a faculty member at Lincoln University, the first degree-granting HBCU in the United States. Azikiwe wrote Du Bois, who was then the editor of the NAACP magazine The Crisis, many times from Lincoln University. As revealed in letters archived by the University of Massachusetts, Du Bois and Azikiwe often wrote one another in the 1930s during Azikiwe’s time at Lincoln, and the two would connect in person years later as Azikiwe became a leading political figure. Azikiwe inspired another future African leader, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, to study at Lincoln as well. Nkrumah would later become a close friend of Du Bois. As president of Ghana, Nkrumah invited Du Bois to relocate to the country, where the American scholar ended up spending his final years before dying on the eve of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, at age 95.

4. Du Bois helped start an uprising at Fisk University

Du Bois’ relationships with HBCU leaders were not always cordial. In addition to clashing with Washington, Du Bois was eventually fired from his job at Atlanta University for, among other things, insulting Spelman College President Florence Read, who was also an Atlanta University board member. Referring to her as an out-of-touch wealthy white woman, Du Bois alleged that Read “didn’t care about Black people—or anyone else for that matter.”

But Du Bois’ biggest clash with HBCU leadership happened at his alma mater, Fisk, where his daughter Yolande graduated in 1924. By the time Du Bois arrived on campus to attend his daughter’s graduation, he had become angry at the conservative and demeaning policies of the university’s president at the time, Fayette McKenzie. Under McKenzie’s leadership, the school had eliminated the student newspaper, cut many sports and extracurricular activities, and implemented a strict dress code, among other things. McKenzie also acquiesced to southern segregationist policies.

When Du Bois was asked by students to speak while on campus for graduation, he harshly denounced McKenzie, and his words set off a year of on-campus protests against the university president. Du Bois supported the student protests by organizing Fisk alumni against McKenzie and by speaking against him in The Crisis. Du Bois wrote, “Men and women of Black America: Let no decent Negro send his child to Fisk until Fayette McKenzie goes.” The protests and public campaign eventually led to McKenzie’s replacement at the school.

5. Du Bois defended HBCU education even after integration

Despite these clashes with the leaders of certain Black schools, Du Bois remained an advocate of HBCU education throughout his life. In 1960, as legal segregation was being challenged through the Civil Rights Movement and rulings such as Brown v. Board of Education, Du Bois gave a speech at Johnson C. Smith University. He warned that integration might result in fewer Black teachers and in Black students being “taught under unpleasant if not discouraging circumstances” in predominantly white schools.

He further warned, “Theoretically Negro universities will disappear. Negro history will be taught less or not at all, and as in so many cases in the past Negroes will remember their white or Indian ancestors and quite forget their Negro forebearers.”

For Du Bois, Black-led institutions remained key for promoting the history, the identity and the continued progress of Black America. Today, 153 years after Du Bois’ birth, his own legacy is still built into these institutions.