Award-winning author and renowned performer E. Patrick Johnson spoke with Blavity about his collection of oral stories titled Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South. The anthology encompasses more than 70 transparent stories from queer men, ranging in age from 19 to 90, who were born and raised in the Bible Belt. Johnson released the publication back in late 2008, so the book recently celebrated its 10-year anniversary.

The captivating experiences of various Black gentlemen as they maneuver through rigid spaces in the Deep South takes center stage on the pages. Stereotypes are not only confronted but debunked in Johnson’s compilation of interviews and narratives. Recently, Johnson sat down with Blavity to discuss Sweet Tea’s current relevance and share what helped him bring these stories to life.

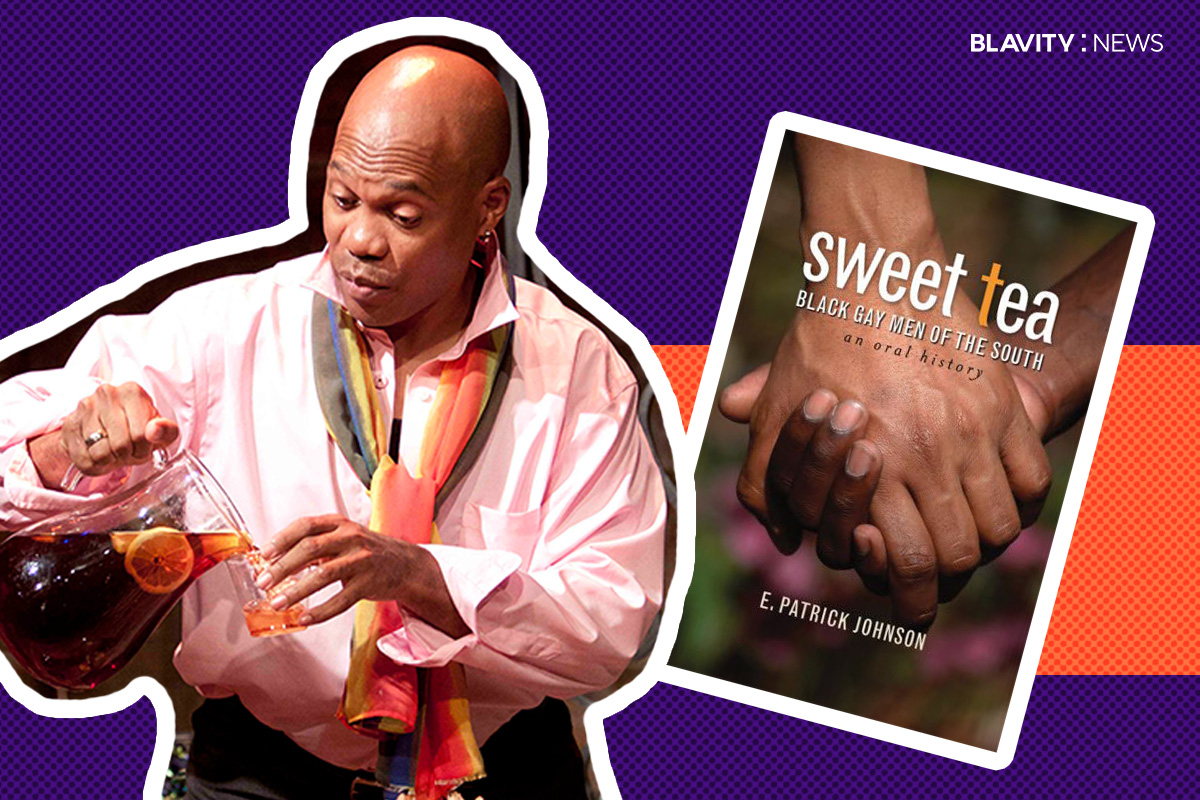

Photo credit: epatrickjohnson.com

Blavity: What inspired you to write Sweat Tea: Black Gay Men of the South, and why the name Sweet Tea?

E. Patrick Johnson: About well over 20 years ago, I was in Washington, D.C., attending an event sponsored by Us Helping Us, People Into Living, which is the organization that was founded by Ron Simmons to do HIV/AIDS activism. At that event, there were a number of older Black gay gentlemen from the South, who were talking about growing up in the South and these wonderful communities that they had and I was mesmerized because I had never heard these stories, being a Black gay man from the South myself.

I made the decision that when I got the resources and time, I would go back to the South and collect these stories. In 2004, that’s what I did. I went back to the South and started collecting stories. The title Sweet Tea actually comes from the drink, sweetened iced tea, which is a staple of the South. I also call it diabetes in a glass [Laughs]. It’s also reffing off of tea as a vernacular term in the Black gay community, which is a form of gossip.

“Sweet Tea” at Durham Arts Council. Photo credit: Paul Davis.

Blavity: How has the feedback been from your family, friends and peers who’ve read your book?

Johnson: Feedback has been amazing — again, because there was no book out there like this. It’s been very impactful for a lot of people, and it has allowed a lot of people to stand in and speak their own truth. Sweet Tea just celebrated its 10th anniversary as a publication, and it’s the gift that keeps on giving because people are still being impacted by it.

Blavity: That’s amazing. How has religion impacted your experiences as a Black gay man in the South?

Johnson: [Laughs.]

Blavity: You knew it was coming.

Johnson: You know, one of the interesting things about doing the research for the book and interviewing people is I grew up Southern Baptist. I grew up in the church, sang in the choir, and so forth. When I started contacting [people for] these interviews, I thought everybody would be Baptist, Methodist or COGIC. What I found is that there is a whole array of religious and spiritual practices in the South, among the Black, gay folk I interviewed — that was really eye-opening to me.

One of the things that was also interesting to me was that no matter what one’s relationship to religion was — whether it be they're entrenched in the church or they don’t go to church — no one is untouched by the church, living in the South. There are some men that I’ve interviewed who’ve left the church because of its homophobia. Then there are folks who are committed to the Black church — who are in it — hold offices and still participating because they believe that the God they serve is the same God that also loves them, despite or in spite of their sexuality. So it’s a whole range of relationships that people have with religion.

“Sweet Tea” at Durham Arts Council. Photo credit: Paul Davis.

Blavity: Which oral stories did you relate with the most?

Johnson: [Laughs.] Myself. That’s a hard one, because I interviewed 77 men for the book and some of the stories are quite different from my own. I didn’t have a bad experience growing up in the church. My church was not homophobic; my pastor really didn’t talk about homosexuality at all. One thing that I can relate to though is being bullied, being called [a] sissy, being called a f****t, being picked on because of my soft-spoken voice.

I also had — and still have today — a big butt. [Laughs.] So I was teased and bullied about those things and that was a common thing among a lot of the stories that were told to me, as well. Also, the thing that I can relate to is feeling like I was the only one and not having any role models; for someone to pull me to the side and say, "No baby, you ain’t the only gay person." Again, that was one of the things I hoped the book would help alleviate.

Blavity: Thank you so much for your transparency.

Johnson: Oh, absolutely!

Blavity: What made you adapt Sweet Tea into a one-person stage play?

Johnson: When I started doing these interviews, I wasn't thinking about a performance at all, even though I am a performer and teach performance. But after listening to so many stories and meeting so many great storytellers, I realized that a book was not going to be able to capture the dialect, and accents, and mannerisms, and verbal tics and all of those things on the page. So I said this needs to live off the page.

“Sweet Tea” at Durham Arts Council. Photo credit: Paul Davis.

Johnson: I decided it would be interesting to take the story on myself. Two years before the book was even out, I started performing some of the stories from the book, and that became a whole other thing, and people started asking me to perform the stories.

In 2009, a producer approached me about turning it into a full theatrical production. In 2010, the production premiered in Chicago at About Face Theatre for a five-week run. Then it traveled to a number of different places and ended at The National Black Theatre Festival. [I] performed there in 2015, I think it was. It’s been quite a journey from a book to a play and now a documentary film.

Blavity: Tell me a little bit more about that.

Johnson: [The documentary] will be showing — an excerpt — at Harlem Stage as a part of Pride Month, and I’m really excited about that. How that came about was the theatre production premiered in Chicago. There was a colleague of mine who teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, John Jackson, Jr., who’s also an anthropologist and a documentary filmmaker.

[He] was in the audience and said, "This needs to be a film." So I said, "OK." Several years passed and nothing happened. He circled back and said, "Yeah, we really should think about turning this into a film."

His original idea was to make a documentary film about the making of the play. We started filming. Of course, it became about much more than that. So the film is about my own journey back to the South as an openly gay man and my relationship to my community. It’s about what's happened to these men, since I originally interviewed them over a decade ago. It’s about the making of the play, and it’s also about me performing the men's stories in front of them.

“Sweet Tea” at Durham Arts Council. Photo credit: Paul Davis.

Blavity: I can’t wait to see this! And you did say you’re still the professor of performance studies?

Johnson: Yeah. I am a professor of performance studies and African American studies at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Blavity: So have you used any of your pieces, as far as class discussions or assignments for your students?

Johnson: Oh yeah! I’ve taught Sweet Tea excerpts a number of times in my classes. That's what's been interesting to me about the book and the performance. That’s why I get invited to colleges and universities; because people are teaching the book — and a number of different courses, not just ones on sexuality. It gets taught in anthropology courses [and] in history courses, because people are interested in the content of these narratives, in terms of what they say about Southern history, about Black history and about Black sexuality in the South.

Blavity: I know you’re still working on that documentary, but are you working on writing another book?

Johnson: Yes. [Laughs.] I just published the companion to Sweet Tea called Black. Queer. Southern. Women.: An Oral History and that book came out in November. That’s actually an orchestry of Black southern women who love women. I interviewed 79 Black women in the South about their experiences growing [up] Black and same gender loving.

Then I have another book coming out in the fall called Honeypot, which is creative nonfiction. I created a character named Ms. Bee. As a reader, you don’t know if she’s a human or a bee. [Laughs.] She kidnaps a character by the name of Dr. EPJ — I'm sure you get the parallels. She kidnaps him from his house in Chicago, and takes him to a hive to meet her sisters and insists that he listen to their stories. They have this antagonistic relationship, but over the course of the book, they come to understand one another and maybe even like each other. That book is coming out in the fall and it’s actually using some of the same oral histories that I created for Black. Queer. Southern. Women., so I’m busy.

Blavity: That’s good!

Johnson: Thank you.

“Sweet Tea” at Durham Arts Council. Photo credit: Paul Davis.

Blavity: My last question for you is what advice would you give to young, gay men who are still navigating their sexuality?

Johnson: That’s a great question. One of the things that I tell young folk all the time about coming out being gay is to love yourself more than your fear of losing a loved one. What I mean by that is a lot of people are afraid to stand in their own truth, because they fear rejection from their parents, from their friends, from their community. The more you internalize the homophobia and the more you refuse to stand in your own truth, the worse it’s going to be — because you hate yourself.

You stand in your own truth and say, 'Look this [is] who I am. I’ve gone through the process [of] figuring out who I am, and you need to go through your own process of accepting me for who I am. Until you do that, you do what you need to do and I’m going to go on living.' That’s the most productive thing for young people to do.

There are so many young people who end up committing suicide or try to harm themselves because they are afraid of being rejected by their peers [and] by their family. They should know that they’re not alone and that there are other folks who they can call family.