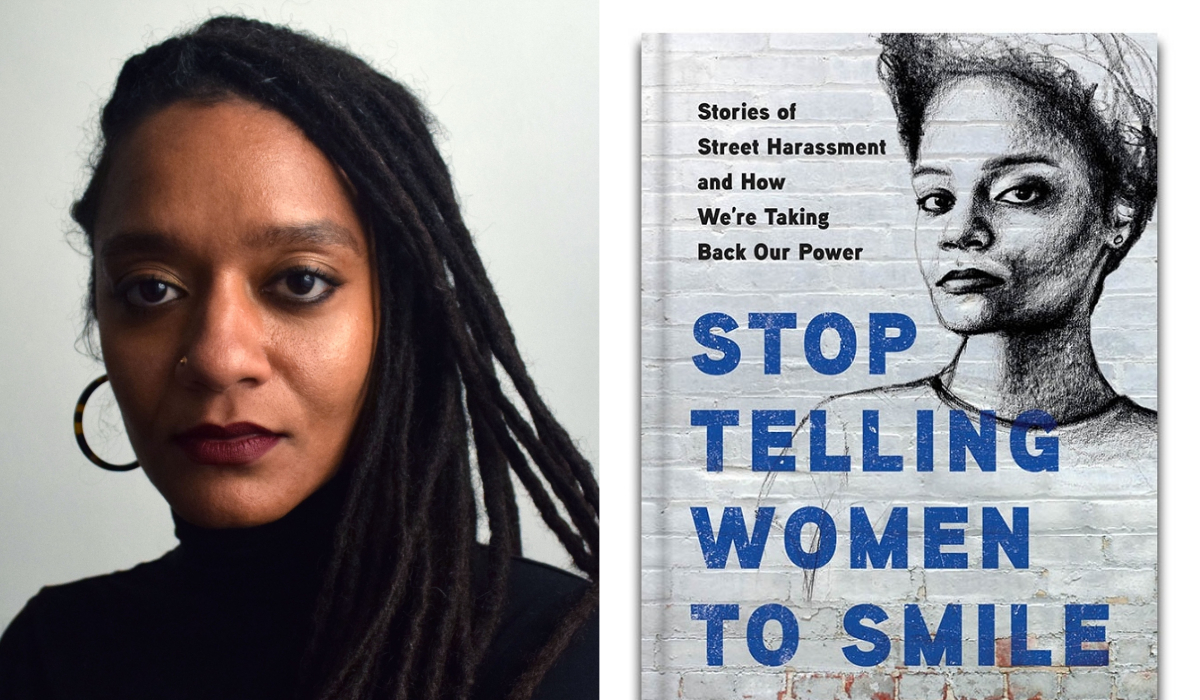

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh is an artist and activist based in Brooklyn, New York, who recently released her first book, Stop Telling Women to Smile, in February 2020. Stop Telling Women To Smile, tells the stories of women who have been victims of street harassment. In the book, the Black-Iranian creative from Oklahoma City addresses various forms of rampant harassment and the proactive actions that could possibly counter them.

According to a 2019 study conducted by the Center on Gender Equity and Health (GEH) at UC San Diego, Stop Street Harassment, California Coalition Against Sexual Assault (CALCASA), and Promundo, "Sexual harassment and assault cause people, especially women, to feel anxiety or depression and prompt them to change their route or regular routine." Additionally, street harassment is not an issue that's limited to major cities. It also occurs in small towns and rural neighborhoods, and this misconception is part of what motivated Fazlalizadeh to speak with women who have reported being harassed in these areas.

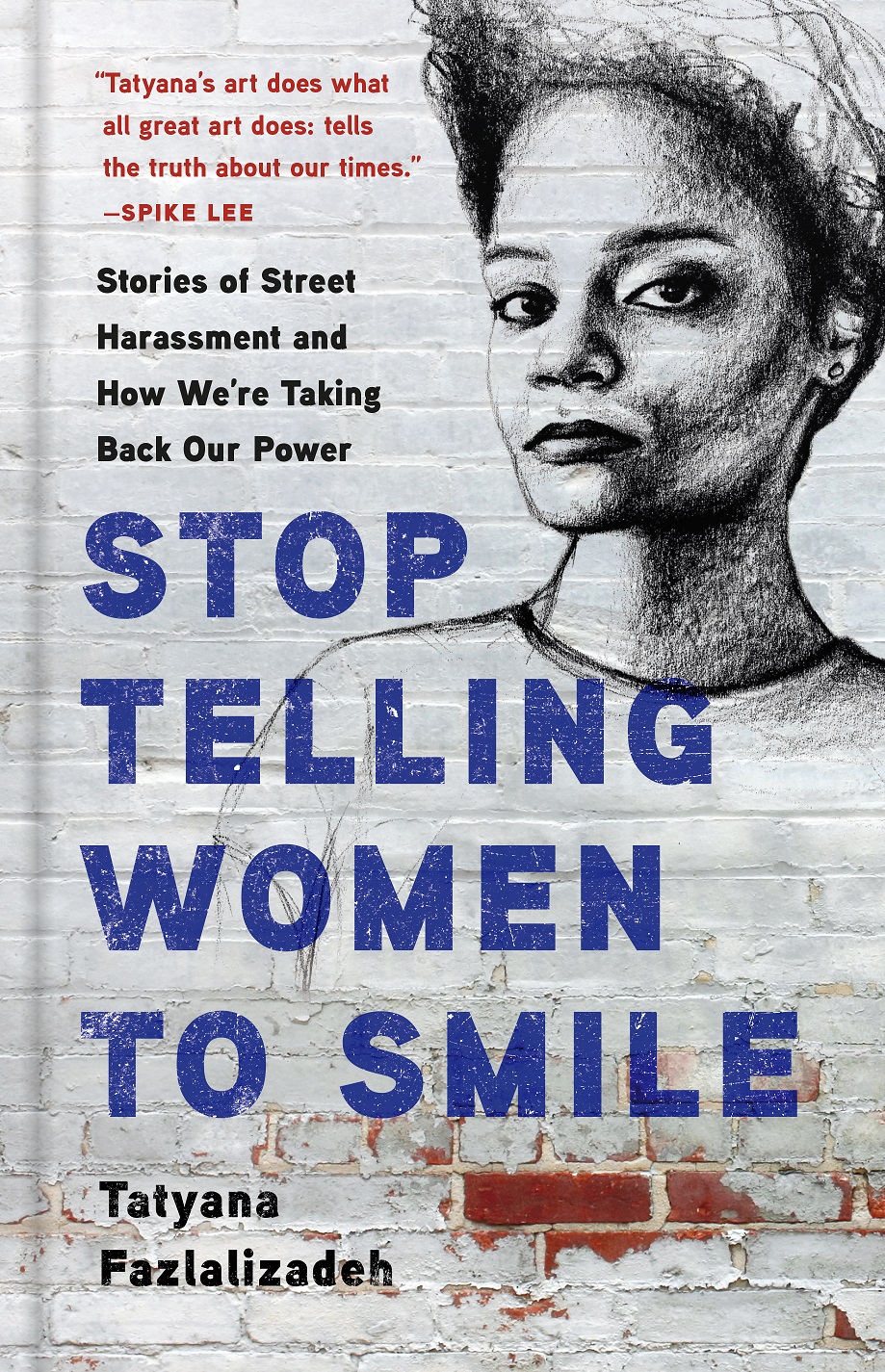

Prior to formulating the book, Fazlalizadeh is known for being the real artist behind character Nola Darling’s artwork in season two of Spike Lee’s Netflix series She’s Gotta Have It. Before writing her book, the talented artist also produced a street harassment mural project portraying women who represented various backgrounds and ethnicities. The street project placed the women’s statements and faces on Brooklyn buildings, and eventually it spread to other cities, like Boston, Los Angeles, Oakland and many more. The project offered a bold and combative assertion by women in an environment where they are so often made to feel uncomfortable and unsafe.

“I don’t need your comment, your compliment, your insertion into my life,” one of Fazlalizadeh’s works reads.

Her book Stop Telling Women to Smile is broken into two parts. The first part features interviews with women who have experienced some variation of street harassment, whether it be physical or verbal. In the second half, the artist and author enmeshes her impactful artwork with activism. Additionally, it shares a necessary message to men along with her hopes for the future.

Photo credit: Tatyana Fazlalizadeh

Photo credit: Tatyana Fazlalizadeh

Blavity spoke with the street artist, activist and writer about her creative work.

Blavity: You started your street harassment street art project back in 2012. What made you want to transform it into a book?

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh: I wanted to write this book so that readers could gain a deeper and more well-rounded understanding of street harassment and the different ways it plays out. The street art series begins with the process of interviewing individuals about their experiences with sexual harassment and the particular ways that their other identities affect how they are treated outside. This book allows readers access to those interviews. I also discuss my own history with sexual harassment and my journey to becoming the type of artist that I am.

Blavity: How did you go about finding women to interview?

Fazlalizadeh: I did an open call for the people who are featured in the book. I’ll use my social media as a space to connect with people in Brooklyn and New York. Social media is also helpful when I want to meet people when I’m traveling.

Blavity: Was your story similar to theirs?

Fazlalizadeh: In some ways, yes. In many other ways, no. In the book, I interviewed nine women and one non-binary person. They all vary in age, race, sexuality, presentation, profession and more. The point of featuring so many people from varying backgrounds is so that we — myself and readers — [see] how a person’s overlapping identities influence street harassment and how that affects the type of harassment; the amount of harassment; and the range of violent harassment. There is always a thread that links all of the experiences, and my experiences also lie on that thread, but the individual stories are very different.

Blavity: How do you think street harassment impacts women?

Fazlalizadeh: Street harassment affects women and femmes in many ways. There’s the threat of physical violence that is always there. There’s the emotional effect — street harassment is infuriating, frustrating and hurtful. There’s a mental effect — having to mentally navigate what to say or not say to someone on the street. Questioning if a response will illicit insults or assault. There’s a financial toll; for example, when you take a Lyft home instead of walking because you’re avoiding harassment. It affects the ways some women get dressed in the morning, how we’re able to interact with our neighbors, how we feel about our bodies in public and more.

Blavity: It is so frustrating, the extra mile we women have to go to, to protect ourselves. What insight would you like readers to gain from your book?

Fazlalizadeh: I’d like readers to leave the book with a deeper understanding of how people who are different from them experience the public space. Having that understanding will hopefully make us all smarter, with a clearer picture of how the streets operate for women and femmes, with an urgent need to make it safer for us. There is a chapter directed toward cis-heterosexual men with direct words on how they fit into this issue, and how they can be better.

Blavity: How do you think we can combat street harassment?

Fazlalizadeh: First, by hearing and believing the experiences of street harassment that women tell us. From there, I think being an active bystander is essential. Standing up and interfering when you see harassment happening — talking with friends, family, colleagues about it. Sharing resources about the reality of it, and being aware enough to recognize when it happens in front of you.

I think in order to see widespread change with street harassment, there must be a societal shift in how women and femmes are treated across the board. Street harassment falls on a spectrum of violence that women endure, and we must tackle the entirety of sexual abuse [violence] and misogyny to see changes to street harassment.

Blavity: Very insightful. Aside from your book, are you still creating art? What other projects are you working on?

Fazlalizadeh: I’m an artist. In the past year, I’ve created a citywide art project looking at anti-blackness and sexual harassment in NYC, creating murals and public installations in Brooklyn, Harlem, Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx. I created a large scale solo exhibition in Oklahoma City called Oklahoma Is Black, with paintings, video, and installations featuring the faces and stories of Black Oklahomans.

I’m currently illustrating a children’s book about Black girls. I’m conducting interviews and producing artwork for a project called America Is Black— multimedia project that focuses on telling the stories of Black Americans in particular cities across the country. And I am in the studio continuing my oil painting practice.