My father was not perfect. A Nigerian immigrant born in the late ‘40s, he had his work cut out for him raising two little girls on the South Side of Chicago during the ‘90s. Naturally we butted heads quite often. Some days our arguments stemmed from our cultural differences, other days it was simply normal tensions that brew between daughters and their fathers. Despite all this, there are memories that I have of him that will remain with me until the day I take my last breath. From school science projects and “Harry Potter”, to my love and obsession for films, my father was pivotal in molding me into the woman that I am now. When I laid him to rest on a bitterly cold day the year I turned twenty-three, I knew that despite everything, he’d done the best that he could. Unfortunately, there are millions of people, especially in the Black community that cannot say the same about their fathers.

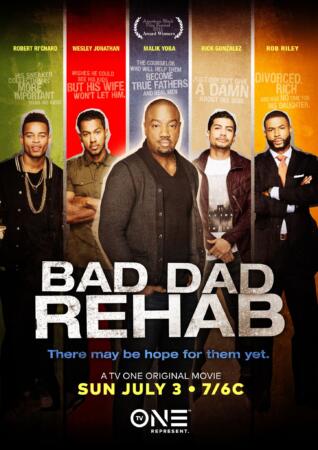

TV One’s original film “Bad Dad Rehab” follows four fathers whose parenting skills leave a lot to be desired. On their journey to do better, the men find themselves enrolled in a focus group that supports men as they strive to become better fathers and overall human beings. Ahead of its July 3rd premiere, I had the opportunity to chat with film star and producer Malik Yoba. I also spoke with the majority of the gentlemen in the cast, Robert Ri’chard, Rob Riley and Rick Gonzalez. Wesley Jonathan also stars in the film. We chatted about finding their way into their characters, the pain of broken families, and the fear of fathering.

Aramide Tinubu: Hello gentleman, it’s fantastic to be chatting with you all today about your upcoming film with TV One, “Bad Dad Rehab”. Mr. Yoba, I know you were really inspired to be a part of this film because you started a foundation when your daughter was born to make sure that fathers knew their rights. What inspired you to create that foundation to give fathers, and specifically fathers of color a voice?

Malik Yoba: I think a lot of it just comes from my own relationship with my father. My father was very present, very domineering; he was a very strict presence so he always pointed out how lot of my friends didn’t have their fathers around. He was a determined cat, so I come to it naturally in terms of wanting to help people and that sort of thing. Becoming a father myself and realizing the lack of resources inspired me. I knew that it was a problem and I’m a self-starter and entrepreneur, so I always looked at opportunities in both the non-profit and for profit space to create products and services for men. Reading this film, it was so close to a piece that I’d written. Literally, Rick [Gonzalez]’s character in my film was this Latino guy who has a kid against his wishes and he’s a barber.

AT: Oh wow, that’s exactly who Rick’s character Pierre is.

MY: Yeah, it was that close, it was just one of those things. I was grateful that I woke up to a text message from my manager saying you have an offer to star in this film. It was just one of those things that you know you have to do, and I’m just glad that everyone else felt the same way. It’s been such a good thing, not just producing the film, but also working with TV One to market the film as well. It’s been very important to me to be involved in how the message is conveyed to the consumer. It just made sense all the way around.

AT: Wonderful! Mr. Gonzalez, I’d love to chat more about your character Pierre. Where did you draw your inspiration to play him from, and where do you think his fear of becoming a father comes from?

Rick Gonzalez: My daughter is about to turn three-years-old and for me, the experience of being a dad is very spiritual and arriving at this character was very spiritual. I really wanted to understand why Pierre would turn his back on the responsibility of raising his child. I had to understand how that made me feel personally, and then I had to do the homework on understanding why Pierre would do that. I really had to put my feet in his shoes in order to feel that, and to see where that would lead me. Pierre’s emotional scenes were shot in the final two days of filming so that helped as well, because I was able to go on this journey with him the entire time until I arrived at the climax.

AT: That must have been extremely emotional for you.

RG: Yes, each father in this film had to recognize their truth. I think recognizing their truth and owning it is where their healing began. So that’s how I got into what Pierre was thinking. At the premiere at American Black Film Festival, we all talked about why we cared about these characters, and I said that this was ordained for me. For me to be a dad now, and to take on Pierre I think it was the perfect thing. Each character in this film recognizes the mechanisms that are inside of them that makes them turn away from enjoying the act of being a dad. We really felt that our writer Kiki [2015 TV One Screenplay Competition winner Keronda “Kiki” McKnight] had a good hold on the commentary and the truth of what these dads were going through. I think that this film really spoke to all of us.

AT: Fantastic! Mr. Ri’chard I know that you play Tristan, can you talk about who he is?

Robert Ri’chard: Yes, I play Tristan. He’s the classic deadbeat dad. He has five kids, four baby mamas, three cell phones, and two hundred sneakers. The film sort of opens on Tristan and you can see that in society how a lot of men glorify self-preservation and selfishness. Over time with Tristan, we discover where that comes from. That’s the beauty about “Bad Dad Rehab.” So many guys have the nicest car or the best sneakers or the most fly haircut, but you don’t see them being responsible with their seed. We get to examine that. It’s like, how are you glorifying yourself and not taking care of the most precious thing in your life?

AT: Where does Tristan’s fear of being a father stem from?

Robert Ri’chard: I think that a lot of that is the social scene. In minority communities especially, it’s not praised enough to be a great father. It’s praised to have a nice car or money in the bank, but we don’t as a community praise fatherhood. I think that’s probably the most emotional thing for men and it’s probably the most hidden thing in their hearts because it’s like, “Look I don’t even get any credit for these things.”

AT: Well just to push back against that a bit, should men get credit for doing what should be expected?

Robert Ri’chard: The credit comes from not doing it alone, that’s the brotherhood aspect. In the film you see men caring about and helping other men. That ‘s what I mean about the support and encouragement from man to man. If we don’t have dialogue or if we’re scared to as men to ask for help, that’s an issue. It should be, “What can we do together to lighten the load?” That’s just simple physics. That’s community right there. Men don’t even know that they can talk to other guys, and that’s what we introduce in this film. That’s where the rehabilitation comes from, when they continue to show up.

AT: For you Mr. Riley, what really struck me about your character Jared was the fact that though he was financially available, he was emotionally unable to father his child. How did you approach your role?

Rob Riley: Well, I was raised by my mother, so the inspiration is pretty much right there. For me, I was fortunate enough to be cast in this film and participating in a redeeming story is one of the way that I can make sure that what happened to me doesn’t continue to happen. My father passed away in 2008 and we never had the chance to reconcile.

AT: Oh, I’m so sorry.

Rob Riley: Thank you, but I did not attend the funeral. I didn’t know him. I come from my own version of having a deadbeat father. Though I had some amazing father figures in my life who I am so thankful for, I had to piece it all together like it was a jigsaw puzzle. Luckily, these great men including my uncles and a few older cousins were able to contribute to my circumstances. As far as Jared being someone who is financially available, that’s a bit of what our child support system has built. This can be traced back to slavery and tearing families apart. As we began to implement some of these other programs; it made it so we had this systematic disconnect of families in America.

AT: Oh certainly, even into the way the welfare system was structured during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Rob Riley: Yes, and then there is this idea that it is better to do it by yourself rather than trying to figure out how to co-parent. I don’t agree with that. My mother is an amazing mother, she’s a superwoman and she taught me how to be a fantastic human being. However, she could never teach me how to be a man, it’s not possible. I could go on and on to be perfectly honest because it’s so close to my heart. I live every day having no father to turn to.

Continue to page 2…

AT: Let’s keep chatting about money. Mr. Ri’chard, what I found so interesting about Tristan is that he’s super fun loving and carefree, almost like a big brother to his kids. However, he’s always broke. Though kids are extremely expensive, why is there so much emphasis on money versus actual time spent when it comes to rearing children?

Robert Ri’chard: It’s funny because if you asked Tristan he would say that exact same thing you’re saying. He would say, “My kids know me. I spend time with my kids.” He has secret handshakes with his son and he knows what his kids are doing in school. But it’s the relationships with the women in his life who are demanding partnerships that he takes issues with. This is really Tristan’s resentment for all of the hard work he had to do as a child, because he had no father to take care of him. So in the back of his subconscious, it’s, “I’ve worked, I’ve slaved, I’ve taken care of everyone for so long so now, it’s about me taking care of myself.”

AT: He’s infantilized. It’s like he’s a child again.

Robert Ri’chard: Right!

AT: It’s so interesting.

Robert Ri’chard: Yes and he’s also like, “Don’t look at me as someone you’re just going to lean on just because I’m there.” He wants to do half, but it’s not coming from a pure or heartfelt place. A heartfelt place would be to say, “I’ll do everything I can for my wife, for my kids, and for the mothers of my children to make sure that I provide for my kids.” But it’s a learning process for him.

AT: Lets talk about cycles. I know that impoverishment; institutional racism, segregation and so forth all contribute to the fact that fathers are absent in 1 out of 3 homes in the United States. Do you think it’s possible to overcome the cycle? And also, where should the blame be placed?

MY: I don’t think it’s about blame, I think it’s about becoming informed. Generally speaking, people who come from loving, healthy and nurturing environments tend to become those same types of people. Those who don’t come from those types of households sometimes break the cycle, but often times they do not. Personally, I don’t believe in placing blame, but I do believe in taking responsibility. As artists I’ve always felt that we have the platform to tell stories that matter as long as we understand that it’s a collective responsibility. The saying that, “It takes the village to raise a child” is true. Ultimately “Bad Dad Rehab” for Kiki the writer, and those of us who are a part of it, it’s an act of responsibility. If we do that then we don’t have to have a conversation about blame. That’s why it was so beautiful doing this film, with this cast and the crew; everyone knew this was relevant. We wanted to tell this story and be responsible. We didn’t want to be preachy; we wanted to be funny, entertaining and insightful. We wanted to be vulnerable.

RG: Yes, to echo what Malik said, I think that this film is not about blame but instead, it’s about life. Life has problems and troubles and we can never escape that. However, it’s about addressing our own issues and understanding what we actually can control. Kiki was very conscience about not bashing the men in the film, but instead saying, “Hey there is a huge disconnect in our community that we need to address. It needs to be done in a way that is not indicative in creating harm, but to highlight the inconsistencies.” I think that was her mission, and I think we all connected to that. That’s why we’re all so proud of this film because we feel like it’s a good film in itself, it’s a quality film that people will watch and enjoy,

AT: Oh definitely it was fantastic. What was so poignant in the film, was the willingness of other men to step up. Malik’s character Mr. Leon starts the support group for men. However, if fathers do not step up or are unable for some reason, what responsibilities do we have as a community to begin fathering these fatherless children?

MY: It takes a village, it’s not even a question. Well… it is a question for some people because they think, “That’s ain’t on me.” But, the people who generally say that aren’t the people who are working in the community. So many people are walking around broken. That’s why Orlando happened, that’s why so much of this unrest is happening. We have never lived in a country that has said, “Hey I’m here to take care of you.” How about compassionate government? How about saying all of my preverbal children are taken care of? So yes, we are responsible when it comes to taking care of each other.

RG: I think what makes it so difficult is that no one wants to be preached to, no one wants to be told what’s wrong with his or her life, so it’s a song a dance of communicating and uplifting and intervening. What’s the right way? I’ve been blessed as an actor, and sometimes you get to be a part of something more that sparks a conversation. Hopefully this conversation can help. I think it’s planting seeds. I know that many films I grew up with planted seeds, and I’ve had many wonderful conversations over great films.

Robert Ri’chard: No one watching “Bad Dad Rehab” will say, “Oh yeah I saw it.” They will say, “Have you seen that film, it’s great?” The movie is just so entertaining and when you see it it’s like, “Where do I stand as far as being a father to my kids or a son to my father, a father in my community, or a father to my state? How am I taking care of what I should be proud to be responsible for?”

AT: Going back to what Rick was saying about Screenwriter Kiki McKnight being intentional about not bashing men. What do you all think the main difference is between motherhood and fatherhood?

MY: (Laughing) Well, I’m raising three kids and last week I was in Miami with my son who is fourteen; kids are different at different ages and within six months they can change so much. He’s fourteen, but he’s sprouted up to six foot one. I’m looking at this kid and having him engage in this world. When we got back to New York I was talking to his mother and I was talking about the importance of us doing “man shit.” I told her, “He’s missing that right now.” But, a year ago or even six months ago, I might not have seen it the same way.

AT: Oh I see.

MY: His mom has been a great mother, and there are certain things that she knows she can give him, and there are certain things that have to come from me. Sometimes it’s not the obvious things. It’s a beautiful thing to be a father. I think that’s why I’m so proud of this film, because I know the pain that I’ve been in fighting for my rights as a parent and not having that support. If people don’t get anything else from this film, if you’re a dude and you’re dealing with an angry or bitter ex and you are actively working on your stuff as a man to get through the layers of the ego and the pain and the triggers and all of the stuff that we often don’t have a language for… If you are really on that path and you have the capacity to pray for another person’s pain that is trying to hurt you, that is where the transformation happens.

AT: Do you feel like deadbeat fathers are broken people, or has society contributed to that more than their own unwillingness to step up?

Rob Riley: I think it’s a mixture of both. When I was in college I had a girlfriend whose father was out of her life and suddenly came back. So, she had a nice car and we were able to vacation with him, but she never cared about him. She called him by his first name; she had no respect for him at all. She literally just took his money because she knew he just felt so bad. System aside, that’s his fault. Even if you’re in a situation like Shawn in the film where the woman is seemingly making it unnecessarily difficult for you to parent your child, you have to fight for your kids. That is the mentality that I believe you have to have no matter how difficult it is. If your child is around the corner or a couple of blocks away or even in the country, you have to figure it out.

AT: You don’t have an excuse at that point.

Rob Riley: No you don’t.

AT: Time spent in itself is just so important

Rob Riley: And patience, understanding that as long as you are committed to figuring it out then you can figure it out. That’s what this film shows. Nothing in life is wrapped up in a nice tight little bow. However, that doesn’t mean you don’t try to get there.

AT: What do you want the audience to take away from “Bad Dad Rehab”? It was such a moving film to experience, but it was a ton of fun to watch despite some of the really hard topics that were discussed.

Rob Riley: First and foremost, I want people to enjoy this film because as you said, it has its moments of levity and its got its moments of seriousness, but it’s a great film, it’s a complete film. I want people to enjoy “Bad Dad Rehab” because if they enjoy it, then they will spread the word and that means that the message will be heard by that many more people. There is that much more opportunity for this message to bounce into someone’s ears, and for them to figure it out. That is probably the larger thing that I want. But, the most important thing is that it is not too late. Oh my God, I wish somebody had showed my father a version of this film so that before he passed away he could have learned that it was not too late. My father died two weeks before my first Broadway production; I was eighteen months out of grad school. This film lets you know that all you have to do is try. It’s so incredibly important for sons and daughters to have their fathers in their lives. It’s so much, but we need you fathers. The longer you wait, the harder it’s going to be.

Robert Ri’chard: I think the biggest thing I’ve learned is that you cannot deliver a message without entertainment. I got to work on this amazing project and to see the cast and crew make something so socially responsible while making it entertaining, I think that’s the biggest thing I’ve taken away from it. That’s the part that opens up your chest, because you don’t even know it’s sneaking up on you.

AT: That’s because the message isn’t being beat over your head.

Robert Ri’chard: Exactly there you go.

MY: Oh July 3rd I just want people to watch this film. Have your barbecue and gather around to watch this.

AT: Well thank you so much gentlemen, this was wonderful. I’m really excited for everyone else to see “Bad Dad Rehab.”

“Bad Dad Rehab” premieres on TV One Sunday, July 3rd at 7PM ET.

Aramide A Tinubu has her Master’s in Film Studies from Columbia University. She wrote her thesis on Black Girlhood and Parental Loss in Contemporary Black American Cinema. She’s a cinephile, bookworm, blogger, and NYU + Columbia University alum. You can read her blog at: www.chocolategirlinthecity.com or tweet her @midnightrami