The election of Kamala Harris as the first Black vice president and the first graduate of a historically Black college or university to hold the position has put the historical significance of HBCUs into focus. Harris’ victory is just the latest in a long political legacy of HBCUs. It is generally well-known that the more than 100 HBCUs in America have produced many of the most prominent Black leaders throughout the country’s history. But the full extent to which HBCUs have been involved in political activism and advancing Black freedom is often overlooked. From the Reconstruction era to the Civil Rights Movement to the current political landscape, HBCUs have been key to fighting for the rights of Black Americans.

Jim Crow era student activism

Growing from a handful of pre-Civil War schools dedicated to educating Black students, such as the African Institute (now Cheyney University) and Lincoln University, most HBCUs were created during or soon after Reconstruction to educate the newly freed Black population in the American South as well as Black Americans from throughout the country.

Protesting on-campus issues

By the 1920s, students at these institutions were starting to organize, even against their own schools’ administrations. When popular Florida A&M University (FAMU) president Nathan Young was fired in 1923 and replaced by a president who accommodated segregation, students spent the next year protesting, boycotting classes and allegedly setting fire to several campus buildings until the school changed leadership.

Two years later in 1925, Fisk University alum and NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois visited his alma mater, where his daughter was graduating. Familiar with complaints from Fisk students that the school’s conservative president Fayette McKenzie was creating an overly restrictive atmosphere and squelching opportunities, including rejecting an on-campus NAACP branch, Du Bois fiercely urged students and alumni to resist. This kicked off a raucous wave of protests and student strikes that succeeded in ousting McKenzie.

Additionally, Howard University has long had a particularly activism-oriented student body. In 1925, Howard students were inspired by Fisk's student body to go on strike and force the school to eliminate mandatory ROTC participation for students.

No to Jim Crow

Branching out beyond on-campus issues in 1934, Howard students held two high-profile protests that year. Early in the year, students engaged in Washington, D.C.’s first anti-Jim Crow sit-in, protesting the segregated restaurants of the district in response to pleas from Representative Oscar De Priest, the only Black member of Congress at the time. In December 1934, Howard students wearing nooses around their necks picketed the U.S. Justice Department’s National Crime Conference, which was refusing to discuss lynching as a national priority.

The Southern Negro Youth Congress

HBCU activism reached an unprecedented scope in 1937. That year, students, drawn from nearly every Black college operating at the time, as well as representatives of groups like the YMCA, the Boy Scouts, the Girl Scouts as well as Communists, met at a conference in Richmond, Virginia, and formed the Southern Negro Youth Congress. The group, which had thousands of members at its height, engaged in labor organizing and voter rights education across the South. The SNYC also advocated for social issues such as improved healthcare in Black communities and the addition of African American history in public school curricula.

The SNYC was eventually overwhelmed by the opposition, as the organization was targeted by the anti-communist FBI, the Ku Klux Klan and segregationist police commissioner “Bull” Connor, who took over the police force in Birmingham, Alabama, where the SNYC was headquartered. By 1948, it had mostly ceased to function. But it did not go quietly. In 1946, the organization hosted more than 2000 delegates in an anti-Jim Crow conference held in Columbia, South Carolina. The event, featuring key appearances by Du Bois and Paul Robeson, was, according to a retrospective by the Carolina Panorama newspaper, “the largest human rights event the South had ever seen, with a class analysis of racism and a call for a black and white united front.”

The Civil Rights Movement and HBCU organizing

HBCUs shaped many of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, including Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall and Rosa Parks. Beyond molding leaders, HBCUs also emerged as key locations of activism. Unlike the top-down, elite-driven activism of groups such as King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the activism of Black college students was organic, grassroots and more confrontational.

Sit-ins

Following the legacy of Howard’s activism against segregated restaurants in Washington, D.C., HBCU students began a campaign of sit-ins against segregated establishments in their cities. In February 1, 1960, four North Carolina A&T students – Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Richmond and Jibreel Khazan – began what is now known as the Greensboro Sit-Ins to protest against a segregated Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. Within days, the protest had grown to include hundreds of North Carolina students, and within weeks dozens of similar protests were occurring throughout the segregated south. One of the best-organized sit-in campaigns was organized by the Nashville Student Movement, led by students including Diane Nash and Marion Barry of Fisk University and John Lewis, C.T. Vivian and Bernard Lafayette from the American Baptist Theological Seminary.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

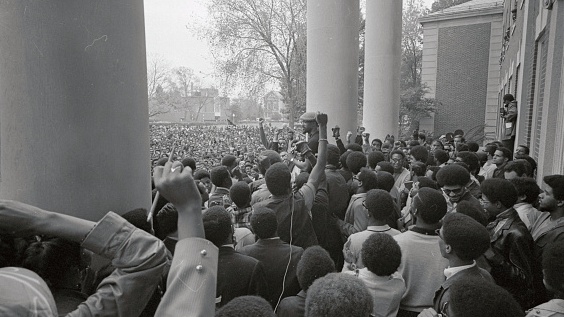

As the sit-in movement grew, SCLC director Ella Baker convened a conference of HBCU student activists from around the country to meet at her alma mater, Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. Among those who came to Shaw on April 15 were Nash, Barry, Lewis and Lafayette, as well as Julian Bond of Morehouse College and Charles McDew of South Carolina State University. These students created a new organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which was youth-led, independent of other organizations like the SCLC and more confrontational than older civil rights groups. SNCC was a crucial force in fighting against segregation and disenfranchisement in the South through the Freedom Rides and the Mississippi Freedom Summer campaigns. Later, under the leadership of Howard alum Stokely Carmichael and former Southern University and A&M College student H. Rap Brown, the group moved away from nonviolence and embraced the Black Power movement.

Nonetheless, students would lose their life to police violence.

In 1925, Fisk president McKenzie called in white police officers against the students attempting to force him out of office. In 1961, dozens of students from Albany State University in Georgia were expelled or suspended for missing exams after they were arrested during a protest march.

Sometimes, opposition to student activism turned deadly. Such was the case in what became known as the 1968 Orangeburg Massacre, in which three people were killed and dozens more injured when police opened fire on peaceful protestors at South Carolina State University. The following year, student Willie Grimes was killed in a dorm raid conducted by police and the National Guard against protestors at North Carolina A&T. Two students were killed by police during a 1970 protest at Jackson State University in Mississippi, but the killing of white students at Kent State a few days earlier overshadowed this attack.

Black student activism in the 21st century

Despite these challenges, HBCU student activism persisted and strengthened the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. As HBCU alumni from that generation, like John Lewis, Julian Bond and Andrew Young, went on to become leading figures in American politics and civil society, new generations of student activists rose to continue the HBCU legacy of fighting for their own rights and the rights of Black Americans everywhere. For example, the students of Atlanta-area schools Morehouse College, Spelman College and Clark Atlanta University, supported by students from Howard and Hampton Universities, rallied and texted in support of Troy Davis, who was ultimately executed in 2011 for the murder of a police officer despite multiple witnesses recanting their testimonies.

Dump Trump

During his time in office, former President Donald Trump made a big show of trying to garner support from HBCU presidents and approving extra support for the schools. At the same time, however, the 45th president’s racism, his administration’s funding cuts for financial aid and opposition to affirmative action all galvanized HBCU student opposition to the Trump administration and the Republican president's supporters. For instance, as Blavity previously reported, Dillard University students came out in force and endured pepper spray when former KKK Grand Wizard David Duke participated in a Senate debate hosted on the school's campus.

Keeping the momentum going

But even though the Trump presidency and its resurgence of white nationalism inspired HBCU student activism, Trump leaving office has not eliminated political organizing on these campuses. Just days after the November 2020 election, Hampton University hosted students from multiple HBCUs in an event titled, "You Voted! Now What?" The students from campuses including Texas Southern University, Dillard, Jackson State, and Norfolk State strategized on ways to continue to organize against challenges such as voter suppression. HBCU students may be excited to have alumni like Vice President Harris and U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock in office, but Black students across the country remain dedicated to making sure their own voices continue to be heard, building on centuries of HBCU student activism.