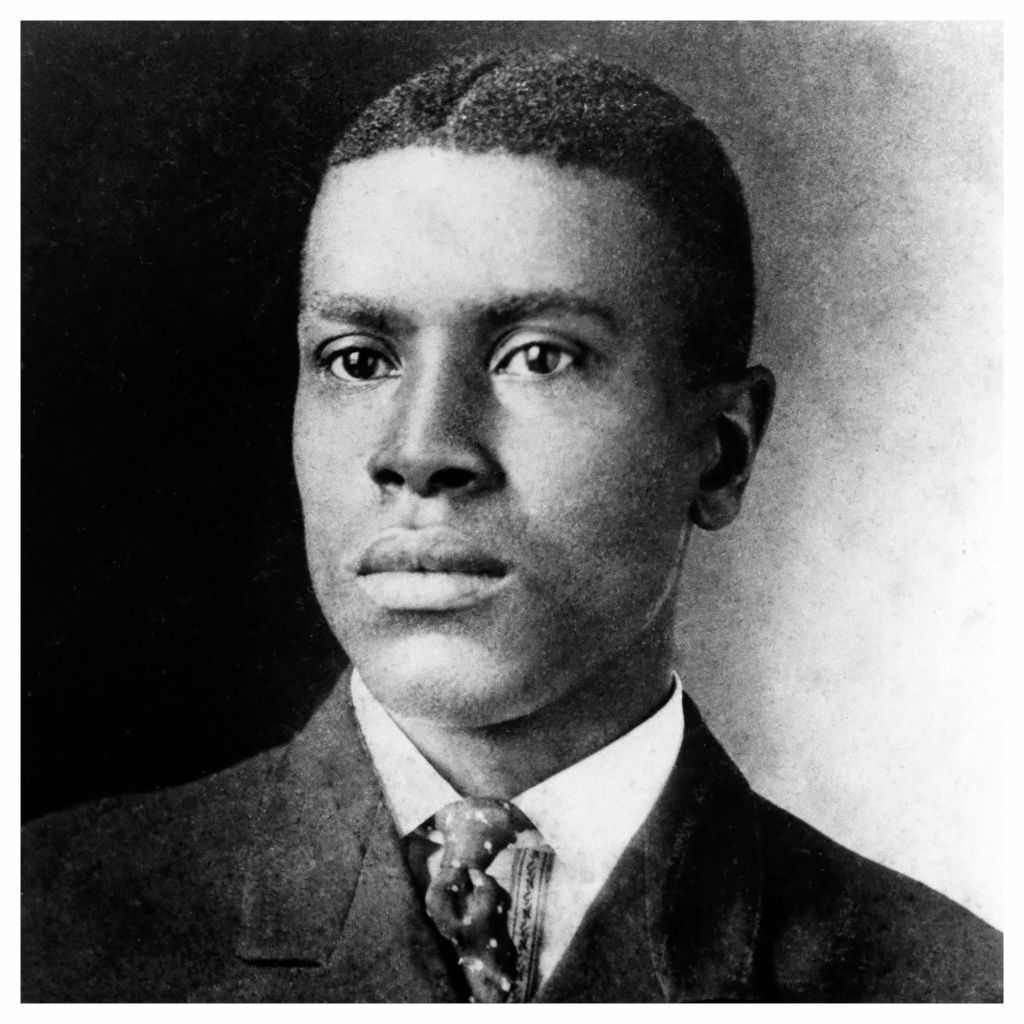

Oscar Micheaux is considered the first prominent Black filmmaker in the United States.

According to the National Park Service, between 1919 and 1948, Micheaux independently wrote, directed and produced over 40 films.

Micheaux’s work highlighted a nuanced scope of the lives of Black people during that era. His films, often referred to as “race films,” challenged racist stereotypes prevalent in mainstream cinema and addressed issues such as lynching, job discrimination, and mob violence.

In 1913, Micheaux wrote and published his first book, The Conquest, loosely based on his experience as a Black man attempting to acquire land on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota during the homesteader lottery of 1904. After receiving great feedback on his first effort, Michaeux completed his second book, The Homesteader. The novel received attention from Hollywood producers who wanted to adapt it into a film; however, when Michaeux voiced that he wanted to be involved with the production and direction, they rescinded the offer.

Forging ahead, in 1919, Michaeux adapted the book into a film, making him the first known Black filmmaker and director, launching his career.

Micheaux broke barriers by establishing his own film company, retaining ownership of his work, hiring Black actors and using innovative production techniques despite limited resources. His 1920 release, Within Our Gates (1920), was one of the first movies directed by a Black director to be shown in white movie theaters.

With the progression of time, lack of distribution and consistent racism in Hollywood, Micheaux’s works were lost and sometimes disregarded in conversations revolving around the early years of cinema history.

In 2015, film distribution company Kino Lorber included Micheaux’s work in a Kickstarter to re-master and digitize classic Black films. In 2022, the company appointed media industry veteran Martha Benyam as Chief Operating Officer. Under her leadership, Benyam and her team worked with partners, including the Library of Congress, to fully restore Micheaux’s “lost” film catalog and make it available for digital streaming and physical purchase.

The recent restoration of the Oscar Micheaux: The Complete Collection marks the first time all his films are in one collection.

Blavity’s Shadow and Act spoke with Benyam about the process behind restoring the collection and what it means to Black cinema.

What inspired Kino Lorber to acquire and restore Oscar Micheaux’s complete works, and how did this project come to fruition?

Part of our mission at Kino Lorber is film preservation and restoration. A multi-disc Oscar Micheaux collection is something we’ve wanted to do since we released Pioneers of African American Cinema (2015). So, in 2022, we conferred with Mike Mashon, the Head of Film at the Library of Congress at that time, and Mike provided us with a list of all of his films known to exist and the locations where each could be found. It was at that point we realized we could assemble a comprehensive Micheaux collection, learning (and hoping) that other Micheaux films may surface in the years ahead. Of the 43 films he is believed to have made, only 14 survive in some form, meaning two-thirds of Micheaux’s body of work is yet to be rediscovered.

Could you elaborate on collaborating with organizations like the Library of Congress and international film archives to restore Micheaux’s films?

All the restoration work was overseen by Bret Wood, our Senior Vice President of Archival Releases, who has produced archival releases for Kino Lorber for more than 20 years. Because Bret had worked with the Library of Congress on Kino Lorber’s Pioneers of African American Cinema, both were eager to collaborate again on the Oscar Micheaux project, which allowed us access to the films in their archives. Fortunately, the films that existed elsewhere were in archives with whom Kino Lorber has good relationships, so we were able to obtain access to God’s Step Children (UCLA Film & Television Archive), Body and Soul (George Eastman Museum), Murder in Harlem (Southern Methodist University), and The Symbol of the Unconquered (Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique). Usually, with a project of this scale, some films will be unavailable because there are companies or collectors who restrict or refuse access to their materials. That was not the case here. Everyone we approached was eager to participate.

Can you provide details on how to find or restore a ‘lost’ film and create an archive?

The first step is detective work in locating and accessing materials. Then, Bret and our team undergo a meticulous process to restore each film, including color grading and reducing audio and visual noise. The team takes great measures and considerable time to ensure our restorations are of the highest quality. We are also always careful to preserve as much of the film from which it was sourced as possible. In this case, none of the original negatives of Micheaux’s films are known to exist. That in itself is a tragedy.

How impactful was Micheaux on the film industry, especially the Black film industry and Black filmmakers?

Micheux pioneered the art of independent filmmaking, setting up his own studio in the 1920s and financing his films by selling shares of his company to white farmers in South Dakota. His contribution to early American independent filmmaking was remarkable, given the times and his meager upbringing as a child of enslaved people with no formal education. He is credited as the first Black filmmaker and made films centered on the Black experience and that challenged racial stereotypes. He’s paved the way for generations of contemporary Black filmmakers, including Charles Burnett, Gordon Parks, Julie Dash, Kathleen Collins, Spike Lee, Ava DuVernay, Barry Jenkins, Jordan Peele, Lena Waithe, Ryan Coogler, and so many more.

Micheaux’s works often tackled subjects like lynching, interracial marriage, and economic exploitation. How do you think these themes resonate with today’s audiences?

There’s no question that Michaeux’s work was unflinching and reflected subjects that were specific to the times. But we live today with the legacy of many of those same subjects – we are only one or two generations removed from Jim Crow. While the world has changed considerably, the films themselves still feel relevant today as a testament to the injustice still faced by many around the world and a testament to the power of film.

How does Kino Lorber intend to highlight how intentional Micheaux was about countering negative stereotypes?

Micheaux created films centered on Black life, which were, in large part, social commentary about the oppressive racism of his time. His work challenged racist stereotypes, an important contrast to the films of the day that often dehumanized Black people. It was important to us to provide historical context for his work, and we were thrilled to work with curator Rhea L. Combs, Director of Cultural Affairs for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, to do that. But we were also careful to let his work speak for itself, presenting his films as vital historical and cultural documents and encouraging viewers and academics to form their own opinions and interpretations. Micheaux’s films will continue to be studied and discussed for generations to come.

Why is preserving films like Micheaux’s, especially for Black media and history, important?

Preservation and restoration keep the work alive and vital in the public’s imagination. It’s not just important to understand our history; it’s also a joy to discover it for the first time or rediscover it again and again. There’s so much to enjoy and appreciate in these films.

How does Kino Lorber plan to make these restored films accessible to a broader audience, particularly younger generations who may not be familiar with Micheaux’s work?

An easy way audiences can discover Michaeux’s films is through our own streaming service, Kino Film Collection. There, you can stream the documentary Oscar Micheaux: The Superhero of Black Filmmaking and restored versions of Micheaux’s films Murder in Harlem, Birthright, and Body and Soul, which introduced a young Paul Robeson to American audiences. The service also includes films from other acclaimed directors like Jean-Luc Godard, Yorgos Lanthimos, Sophie Hyde and Raoul Peck, along with our Oscar-nominated films Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat and Four Daughters, so it’s perfect for anyone who loves film. And we’ve just released Oscar Micheaux: The Complete Collection Blu-Ray box set, which is a comprehensive set that’s perfect for collectors.

How do you hope this inspires similar restoration projects for past Black creatives in film, literature, music, etc?

We’ve been very happy with the interest in our Oscar Micheaux collection, as audiences have explored the films first as repertory theatrical releases and now on our Kino Film Collection streaming service. It’s great to see audiences, and especially younger generations, excited about discovering and rediscovering film classics by Black filmmakers. In the past couple of years, we’ve re-released Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground, Bridgett Davis’ Naked Acts and Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess. Earlier this year, we released Burnett’s The Annihilation of Fish theatrically, and this month, we are releasing the 4K restoration of his landmark film, Killer of Sheep. And we have many more projects in the works.