When Donald Trump was inaugurated in 2017, environmental activists feared the loss of many important, decades-old environmental protections. From stripping away oil refinery safety measures to lifting pesticide bans, some of the most pessimistic predictions for Trump administration's environmental policy are now currently in development.

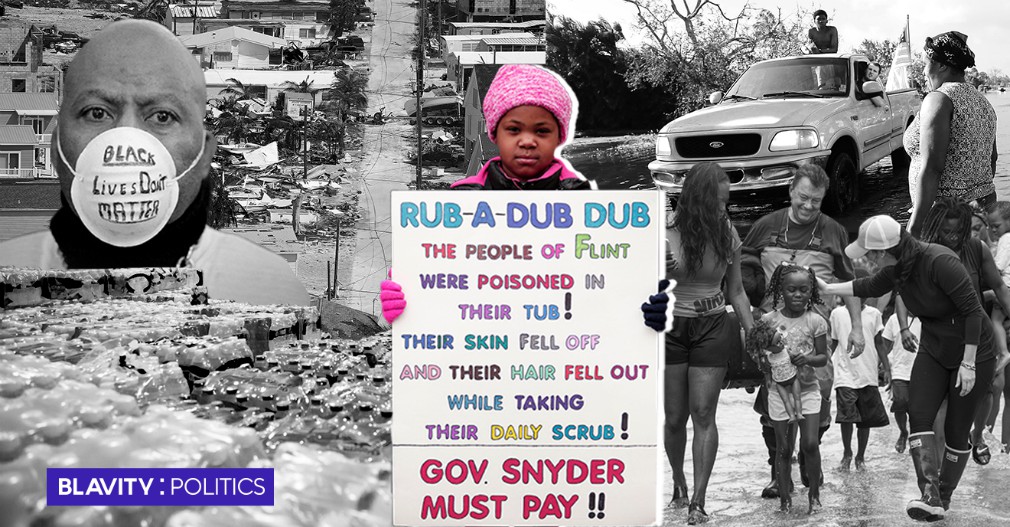

Though the detrimental effects of environmental deregulation will eventually impact all Americans, communities of color have historically been the first and most intensely affected populations. Scholars have deemed this occurrence as Environmental Racism: the extraordinary likelihood people of color will be the first to deal with environmental crises.

Often the “environment” in environmental racism is linked to climate change or meteorological events, yet the inconvenient truth is much larger — including man-made and natural environments. The global, universal nature of environmental racism is why its occurrence is so dangerous and important to identify.

Instances of environmental racism are varied and complex, as well as systemic and not a single issue or event. More often, however, environmental racism exists as either chronic exposure to unsafe conditions or compounding legislative apathy surrounding the health and well-being of communities of color.

1. Chicago

Chicago has the second-highest black population in the United States, with the south side of Chicago being the most concentrated region of black Americans in the country. This makes almost any instance of uncontrolled pollution in the city a likely issue for its black residents, and something city officials should be attentive to. Unfortunately, according to the Better Government Association of Illinois (BGA), Chicagoans in mostly minority neighborhoods have the highest risk for exposure to toxic air pollution.

Most of the toxic air pollution spilling into neighborhoods on Chicago's South Side originates from coal power plants and industrial activities coming out of the South Branch Industrial Corridor. While some of these industries have been in these neighborhoods for years, activists accused former mayor, Rahm Emanuel, of pushing industrial activities from white neighborhoods on the North Side to poorer ones of color on the South Side. This air pollution has had dramatic health effects. According to the Respiratory Health Association, asthma rates among African Americans in Chicago are nearly 75 percent higher than those for white Chicagoans.

2. Denver

#WhyIRun: #Denver's #District9 is home to the most contaminated zip code in the country, & our most vulnerable neighborhoods are further harmed by the I70 expansion and policies that have unthinkingly promoted growth for its own sake. pic.twitter.com/mfH1ykrLLN— Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca (@CandiCdeBacaD9) May 21, 2019

There is a well-documented history of highway construction in America being used to displace black Americans. While some cities have begun undoing some of that damage, others are still planning highway expansions and related construction in majority-minority communities. In Denver, for instance, planned expansion of approximately 10 miles of Interstate 70 recently started. The four-year project has been touted as a measure to alleviate traffic in the city, but the majority of the proposed construction is taking place in large neighborhoods of color, like Northeast Park Hill (43 percent black) and Elyria Swansea (82 percent Latino).

Residential proximity to highways is linked to increased exposure to air pollutants from vehicle emissions. This expansion of Interstate 70 will increase residential exposure to vehicular pollutants when construction is finished, but the construction process itself also has risks. Construction activities will dramatically increase noise pollution areas adjacent to the highway. While noise pollution may seem like an unimportant issue, the World Health Organization (WHO) has linked excessive noise exposure to cardiovascular disease, sleep disturbance, tinnitus, and cognitive impairment in children.

3. Houston

When most people think of “Houston” and the “environment,” they’re probably thinking of Hurricane Harvey and its aftermath. While Hurricane Harvey was disastrous for Houstonians, residents have actually been dealing with another environmental crisis for decades. As the “Energy Capital of America,” gas and oil refineries are a frequent feature of Houston.

Many oil refineries in Houston are located along the Buffalo Bayou, where neighborhoods are majority of color. While most of these neighborhoods are largely Latino, many neighboring communities, like Clinton Park Tri-Community, are predominantly black. Air pollution and toxic spills from Houston’s oil and gas industry have caused cancer risks in some eastern Houston areas to be 22 percent higher than those of the larger metropolitan area. Poverty rates for people of color living so close to chemical factories are high, so medical bills from chronic environmental health complications can quickly exacerbate financial burdens.

4. Los Angeles

As environmental deregulation continues in America, California’s state government stepped in to protect its local and national environments. California’s advocacy for environmental protection, however, have sometimes ignored its own at-risk communities.

The steel milling industry of Watts left its residents (who are mostly of color) to grapple with exposure to startlingly high levels of various toxic compounds. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), some children living in the Jordan Downs housing project have recorded blood lead levels over 200 percent higher than the CDC’s severe exposure threshold. Air pollution stemming from the neighborhood’s proximity to Interstates 105 and 110 have also lead to intense exposure to air contaminants.

The combination of intersecting pollutants in the neighborhood has led the Los Angeles Department of City Planning to conclude that people living in Watts have an average life expectancy 12 years shorter than more affluent Los Angeles residents.

5. Newark

Since 2014, the term “water crisis” has been associated with Flint, Michigan, where infrastructural negligence led to poisonous levels of lead-contaminated water in many black residences. Many of hoped Flint would be the last time water contamination would affect so many residents in an American city, but unfortunately, Newark, New Jersey, is experiencing its own lead contamination crisis, one that could be worse than Flint’s.

Flint whistleblower on Newark water crisis: Lead levels 'look as bad or even worse' than Flint https://t.co/Y9qZPtvX61 pic.twitter.com/uHyBTvHFEw— PIX11 News (@PIX11News) August 15, 2019

Newark is both the largest (by population) and blackest (by percentage) city in New Jersey. Sadly, this means issues with water purity will mostly implicate black people. Drinking water analyses in the city have shown that some residents are receiving water that contains over four times the federal action level for lead-contaminated water. For reference, initial water testing in Flint showed that most residents were receiving water containing only double the federal action level.

The truly tragic part about the Newark Water Crisis is the political disregard for the concerns of the people. Water sampling tests demonstrated elevated levels from as far back as 2017, but the city government failed to stop the Pequannock Treatment Plant from releasing corrosive water into the city’s lead pipes and plumbing. This lack of intervention has now created an emergency primarily endangering the lives of children and the chronically ill.

Well, What Now?

All examples of environmental racism are a function of two important features: location and political apathy. The issue of location is related to America’s history of redlining practices, locking black residents into less than ideal, and sometimes dangerous, areas.

The issue of political apathy is a reflection of how black people often lack attentive political representation, or are only given attention during election season. Both of these factors are fundamentally affected by government policies and legislation. Ultimately, that means the best way to combat environmental racism is with informed, collective political pressure.