Created out of a need to communicate, the Black counterpart of American Sign Language, Black ASL has flavor, seasoning, substance and most importantly, cultural significance to the Black deaf community.

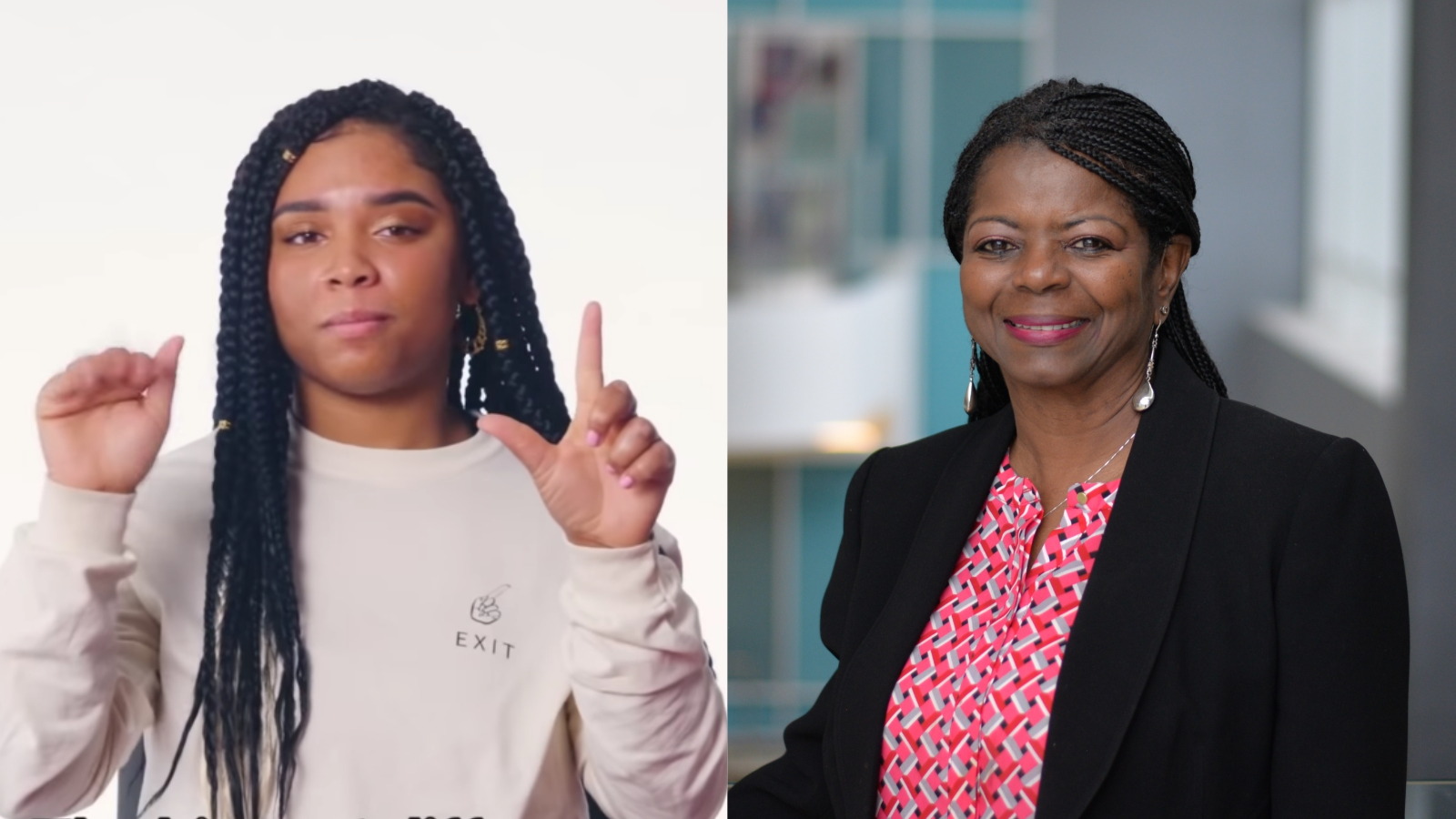

While it's certainly not a new way of signing, loads of people first got wind of this unique form of sign language by way of Nakia Smith, a 22-year-old TikToker who went viral last year for her video showcasing the language, as Blavity previously reported.

"TikTok is a huge platform, so I knew everyone was going to see it. I felt it needed to be out there. Everyone loves to learn something new," Smith told Blavity.

The Eastfield Community College digital media student said she realized her impact the same day she released her first video because she began receiving lots of direct messages.

"I knew I couldn’t answer everyone's questions. From there, I knew that I'd have to continue teaching people what they need to know," she said. "People do need to know that Black ASL is not slang — it’s a language itself."

Luckily for Smith, while she's certainly added to the intrigue of Black ASL, she isn't left to carry the educational burden on her own. A new center at Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., seeks to further educate those interested in the intricacies of Black deaf culture and Black ASL.

Led by professor Carolyn McCaskill, Ph.D., the Center for Black Deaf Studies at Gallaudet University, the first-ever of its kind, derived from the work of a team of researchers, Joseph Hill, Ceil Lucas and Robert Bayley, who studied the intricacies of Black ASL, especially the experiences of Black deaf people in the South.

According to its website, the center, established last August, operates as an outreach center for teaching and learning about the Black deaf experience. McCaskill said that Black deaf culture incorporates language and encompasses values, such as history, people, families, organizations and identities.

“I was very excited that the Center was established,” McCaskill said. “This has been a lifelong dream of mine. I have been teaching at Gallaudet in the deaf studies department specifically since 1996 and I’ve been working at Gallaudet for almost 38 years.”

McCaskill's personal experiences as a young girl in Alabama shaped much of her perception. As a deaf student attending segregated schools, she said she did not realize she was signing a different language than her white peers until desegregation.

“Once integration happened, there was no discussion with us about the language. There was no recognition," McCaskill said.

Code-switching and language preservation then became incredibly important.

“One of my good friends said, ‘you’re signing like white people.’ And so I decided that that wasn’t going to let that happen and I was going to keep my original way of signing," McCaskill said. "I had to think on my feet at the time. When I was with white folks, I would sign their way and when I was with my Black folks, I would sign in my Black ASL way of signing. Many of us, to this day, do that naturally.”

Set to retire last summer, McCaskill said the Center, which builds on the back of courses she’s created in the past, has breathed new life into her career.

“I actually created a course called Black deaf people studies. That course covered the history, the community, the culture and the language of Black deaf people and the Black Diaspora,” she said. “But that was the only course that had been in existence. In 2014, I taught foundations of Black ASL, and there was nothing from then until recently with what’s been going on with Black Lives Matter, and racism and the racial injustice we’ve been seeing more prominently."

With the recent rise in public displays of racial inequities, McCaskill said there is a need for Black deaf people to be recognized.

“Deaf people, in general, have faced a breakdown in communication with police officers and Black deaf people obviously experience more abuse," she said. "And we do want the general community to recognize that deaf people have our own language and it would be very nice if the awareness about deafness were increased."

As the Black experience is being centered in many conversations, McCaskill proclaims that Black deaf people must have a seat at the table.

“We felt like we had been ignored for many, many years. We were unrecognized. We didn’t have equal access. We were not valued and not supported. And with the emergence of Black Lives Matter and the understanding of systemic racism, there was a lot going on and we wanted recognition. We wanted people to invite us to the table, to have equal access, to hear our voices and to recognize our experiences. Not to really exclude us or marginalize us further, but to accept us.”

This is where the Center may find its prominence as it seeks to serve as a resource, providing information about famous or well-known Black deaf people, signs, Black deaf contributions and culture. There is also a strong possibility that Gallaudet will be offering a minor study in Black deaf studies, as early as this coming fall.

“[The Center is] the one place where people will really get to have access to [this] information. Additionally, we are planning to invite a variety of speakers to present on a variety of topics."

The history of Black ASL is very important to McCaskill, especially since just like many other staples of the Black community, Black ASL is often co-opted by non-Black deaf people. While there are AAVE-like signs in Black ASL, there is also a difference in the way standard signs are done. For example, “happy birthday” in ASL might find a person tug on their ears or do the sign for “candles,” but in Black ASL, a person may sign “happy birthday” by tapping on their butt to symbolize birthday licks.

“I have seen some white deaf people use the [Black] sign for ‘what’s up.’ White deaf people are starting to co-opt these things,” McCaskill said. “They might start saying ‘my bad.’ Some of the Black deaf people are starting to feel like that’s not appropriate. That’s our language and we're starting to feel some type of way about the co-opting of the language. These are our spaces, this is our language and we cherish it.”

Overall, however, McCaskill said she wants all people to invest in learning basic sign language. As for Black people, she wants mutual respect and understanding across the hearing and deaf communities.

“I’m just hoping that in general, the African American community can learn more about us because it feels like we’re stepchildren, that people just take us for granted, they overlook us, that we are not in collaboration,” she said. “And I would like people to know that we know more about their history but they don’t know about us and our history. And we’ve got unique experiences that we would like to be able to share with them.”

To learn more about Black ASL, McCaskill recommends reading The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL and viewing its video companion series.