PART ONE: THE PROBLEM

In 2011, Washington Life Magazine, an “insider’s guide to power, philanthropy and society,” published “Access Pollywood: The 100 Best Washington Movies Ever.” It listed, supposedly, the best films about Washington, D.C. prefaced by Arch Campbell, a WJLA ABC7 film reviewer, who bemoaned such grand faux pas as “No Way Out” having a chase scene in which Kevin Costner, evading pursuers, jumped on a Metro subway stop in Georgetown. Needless to say, there ain’t one in Georgetown. But that’s the magic of Hollywood’s imagination.

However, Hollywood’s imagination is limited when depicting the full spectrum of life in Washington, as well as the city as a “character.” The 100 films, ranked by the WL Film Committee, begin with the classic film about Washington politics, Frank Capra’s “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” (1939). It has the city’s “usual suspects”: the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials, etc. And that film, much like nearly all the films on the list, has a familiar pattern: Washington, DC is merely a backdrop or used as background for national politics or issues.

There were a paltry number of films about the non-political life of DC residents in a city of over half-a-million people on the Washington Life movie list. No romances, comedies or dramas that center on the lives of DC residents.

The business of Washington, according to the film list, is exclusively politics. Thus the word “Pollywood” in the article’s title is a conflation of “politics” and “Hollywood.” Except for “St. Elmo’s Fire” and “The Exorcist,” ranked 4th and 9th, respectively, the first 8 films listed are all about politics or power: 1. “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” (1939); 2. “All the President’s Men” (1976); 3. “Wag the Dog” (1997); 4. “St. Elmo’s Fire” (1985); 5. “Citizen Kane” (1941); 6. “The American President” (1995); 7. “Thank You for Smoking” (2005); 8. “Charlie Wilson’s War” (2007); 9. “The Exorcist” (1973); 10. “Dr. Strangelove” (1964).

“St. Elmo’s Fire” is about the lives and loves of Georgetown students; “The Exorcist” is a horror film. “Citizen Kane” (a favorite of this writer) is an odd selection since it’s a faux biography about newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst — the Rupert Murdoch of his day — and doesn’t even take place in Washington, and has a very limited political scope. “St. Elmo’s Fire” is interesting insofar that it is one of the very few films that depicts non-political life in DC. However, what makes it glaringly odd is that it depicts the lives of young white twenty-somethings who attended Georgetown University.

In a city that is 50 percent black there is only one film with a black theme or representation of black life in DC: “Slam (1998), ranked 83rd. However, that film, about a young man who goes to jail and becomes a MC (rapper), fits into the black pathology motif of films like “Precious” or “Monsters’ Ball.”

What is it about Washington, DC — the capital of the United States and the “free world” — that doesn’t lend itself to being a distinct “character” in films? London, Paris, Rome, Tokyo are major world cities and capitals of the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Japan, respectively, cities of national politics. Yet each of these foreign capitals has had films about its people beyond politics. Directors have portrayed each of those cities — like New York, Chicago, Los Angeles and Atlanta — as a “character” in films. But not Washington, D.C. As a matter of fact, Washington is such a nonentity as a film character that no one listed it as an example when a question was posted on Quora: “What are some movies in which a city is one of the most important characters?”

Are the only distinct features of Washington are its own “usual suspects”: politicians, the military, the White House, the Capitol, and monuments? Cities that are not even the ten most populous in the U.S have directors that have made movies that evoke their unique flavor: John Waters in Baltimore, Tyler Perry in Atlanta, and Austin’s Richard Linklater have directed films about the people and idiosyncrasies of their respective cities. But not Washington — or “DC.” Barry Jenkins, the director of “Moonlight,” even made San Francisco and its gentry issue a character in his first film, “Medicine for Melancholy” (2008).

Mike Canning, a film critic for The Hill Rag, a DC-based newspaper on Capitol Hill, and author of the seminal book about films about Washington, “Hollywood on the Potomac,” thinks major film productions about Washington reduces the city to an easily digestible “stereotype.”

“The production attitude towards DC is pretty facile and pretty negative, especially in political terms. Politics and politicians are seen as stupid or venal, I would mostly say,” states Canning.

In ‘Hollywood on the Potomac,’ which begins with Frank Capra’s ‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington’ (1939), Canning argues that the prevailing view of the nation’s capital is negative. In reviewing the content of a few hundred films that have even used Washington at all, Canning says the city is viewed as essentially being politically corrupt. “That there’s a city with actual residents in it really doesn’t resonate. It never has. Washington is a stereotype.”

A good example of this is “Miss Sloane,” which showcases Jessica Chastain as a cuthroat lobbyist in official Washington. Early films like Mr. Smith were more benign and had the classic American motif of the innocent or rugged individual who stands alone and challenges the system, as did Thomas Jefferson Smith played by James Stewart in Capra’s film. However, since the sixties and the collapse of the Hays Code, which prohibited nudity, profanity and proscribed that wrongdoers must be punished, films about Washington have become “more fractious and cynical over the years.”

“Since the sixties when we started getting cynical and post-Vietnam,” argues Canning, “it is much easier to be cynical about Washington because it’s nothing but one scandal after another for most Americans. And Hollywood makes most movies for most Americans. Not for people on the east coast or for people who live here.”

Canning cites three films that fit the prevailing cynical view of Washington DC: “Advise and Consent” (1962) , “Absolute Power” (1997), and “Murder at 1600” (1997). “Advise and Consent” looked at a U. S. Senate confirmation hearing in the early sixties and underscores the maneuvering of senators. Directed by Otto Preminger the film had then edgy “adult themes” regarding homosxuality and McCarthyism.

“But with rare exceptions most of the players,” says Canning, “this parade of senators with star actors — are pretty sour grapes with the exception of a couple of characters. It’s relatively believable but still remains a good entertainment, but it’s very grim.”

By the time Richard Nixon left office, and from what the public learned about Watergate, American presidents were not beyond killing people and trying to cover it up. In “Absolute Power,” directed by Clint Eastwood, who also plays a cat burglar, the POTUS (Gene Hackman) murders his mistress and orders the Secret Service to cover it up. The criminality is only exposed by the cat burglar who knows what happened. Another crime takes place at the White House in “Murder at 1600,” which features Wesley Snipes (before he took a wrong turn in not filing his taxes and spent a few years behind bars). In this film Snipes plays a DC cop who has to go up against a nest of White House vipers who are conspiring against his murder investigation.

In Canning’s view: “The amazing thing is that there are a few movies about Washington that are actually decent, and in fact try to be complex and interesting on their face. That happens occasionally, but that is rare and getting rarer.”

Films such as “The Seduction of Joe Tynan” (1979), which has a more nuanced view of a slightly corrupt senator who was still trying to do good.

“It’s still meant to be entertaining, but it is open-ended and the guy is modestly corrupt but he’s not completely so. And it makes for a movie that’s more interesting, if even not subtle, than others.”

Another is “Broadcast News” (1987). As TV producer, Holly Hunter is torn between three loves: William Hurt who plays a handsome but vacuous bimbo with no integrity but technique; Albert Brooks, on the other hand, is a good journo but isn’t sexy. Hunter’s true love, however, is the news itself and its function as a public trust. (Note: Watch this film during the Age of Trump.)

“Slam,” a 1998 film, and a favorite of Canning’s, is the one exception in his book and a rare one on Washington Life Magazine’s list: it’s about a young black man who lives in Anacostia; he gets involved drugs, goes to jail, discovers poetry and rapping; he is transformed and redeemed. What makes this film unusual is that it is about an aspect of DC that isn’t about politics.

“It has locations all over Washington, including areas of Southeast where I live, that have never been seen before and after in movies. So it is a very distinctive [movie], but hardly anybody has ever seen it. But it stands up. It really does. I’ve screened it for a couple of groups and they are surprised that it was even made. But it has never been followed up or anything like it.”

“Slam” won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 1998; it won the Best Film at Cannes in the Director’s Fortnight category. Distributed by Trimark Films, its total lifetime gross, according to Box Office Mojo: is a mere $1 million-plus, which may explain why “it has never been followed up.” (The District of Columbia Public Library doesn’t even carry the film.)

What makes “Slam” interesting, despite being a box office flop, is that it is a film about DC, the kind of film that the District doesn’t encourage its own indigenous film community to produce. Instead, through tax incentives, toxic films about official Washington — the White House, the Capitol and monuments — are supported. These film productions come to DC, film “postcard” shots over a few days, and then leave. However, it is these types of films that show the most negative and unrealistic aspects of Washington while films that could show DC residents and a broad spectrum of life aren’t produced. Or if they do exist they are so under the radar that they are virtually invisible, as in the case of “Slam.”

The District faces a conundrum: the city often feels slighted that its persona — DC — isn’t recognized as a thriving city beyond being the “nation’s capital.” As the “last colony,” it has to answer to its Congressional overlords who sometimes politically exploit it over issues indifferent to its own citizen’s preferences. Yet because the city itself has not spurred or adequately supported its own indigenous independent film community, who could and would make DC-based films about the city and its residents, the District finds itself encouraging and enticing Hollywood productions, like “Miss Sloane,” to come to DC to make films that tend to have anti-Washington themes.

On the other hand, the city barely recognizes its own indigenous filmmaking community. The city’s agency that handles permits and tax incentives to large scale Hollywood productions — Office of Cable Television, Film, Music and Entertainment (OCTFME) — bestows “Filmmaker of the Month” recognition to DC filmmakers, which are mostly glorified press releases. However, from 2011 to the present, it hasn’t even shown a filmmaker’s reels, highlights, or shorts or features on that agency’s website page, on YouTube channel, or on the city’s cable network, DCN. In other words, the District plays a lackadaisical role in spurring its own indigenous filmmakers to create stories about the city.

DC has not produced any breakout filmmaker or a film that would spark the rest of the country or the national film community to take notice. No “Dear White People” or “Tangerine,” or a romantic comedy or film that would make use of some of the city other sites such as Meridian Hill Park. Or take the example, once again, of Barry Jenkin’s “Medicine for Melancholy” (2008), which has a couple roaming the streets of San Francisco after they had awaken from a one-night stand. It was a low-budget film with thought, feeling, the city as a third character and featured two black actors.

While Washington has shed its “sleepy little Southern city” moniker over the past forty years or so, becoming one of the richest enclaves in the nation, it has not produced a singular persona beyond that of being the “nation’s capital” or the “last colony.”

As matter of fact, when the question of “What is the best unknown independent film set in Washington, DC” is posed, no one can answer it. That is due to the problem that even if DC filmmakers are making productions such as “Districtland” (by Russell Max Simon) and web shows like “Anacostia” (produced and directed by Anthony Anderson), they are not getting wider attention. Making a film in DC is hard and one has to look at the District’s problem of image, infrastructure, and investors.

PART TWO: DC’s Image Problem: It Doesn’t Exist

When large scale productions are filmed in the District to capture the iconic images of Washington, the usual suspects are: the White House, the Capitol, and monuments.

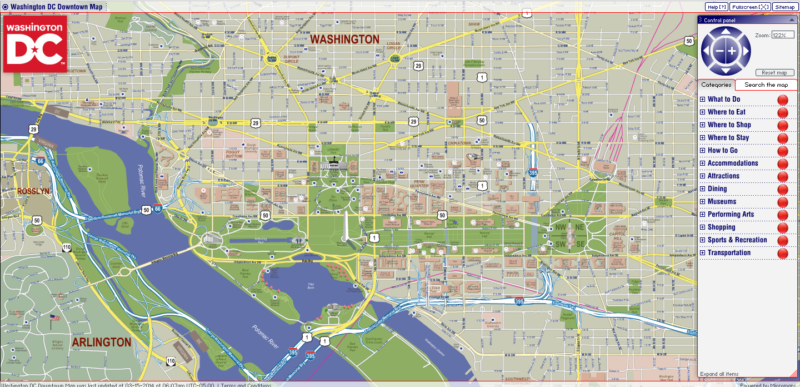

The reality is that DC doesn’t exist as a story in and of itself. Yet the city has numerous scenic neighborhoods beyond the federal enclave: 14th Street NW, Adams-Morgan, Anacostia, Brookland, Capitol Riverfront, Columbia Heights, Downtown, Dupont Circle, Foggy Bottom, H Street NE, Logan Circle, NoMa, Petworth, Shaw, Southwest Waterfront, Tenley Circle, U Street, Woodley Park, etc. Yet if one looks at the map on OCTFME’s website its primary focus is the federal enclave which is the site Washington’s iconic usual suspects: the White House, the Capitol, and the monuments.

DC has an image problem: it is the home of “faceless bureaucrats,” who mostly live in the suburbs. The city is so heavily identified as the seat of the national government that it invokes no other conceptualize of an existence beyond politics. Washington, in films like “Miss Sloane,” is the stereotype that informs the rest of the nation a city where 650,000 people live.

”When you speak to someone who lives in LA they are not thinking of someone who runs a pizza joint [in DC]. Such an image doesn’t come to mind, the way that someone running a pizza joint comes to mind in New York,” ventures Brian Frankel, a DC-based entertainment attorney and the organizer of DC Filmmakers.

DC: It’s a Bourgeois Town

Well, them white folks in Washington they know how

To call a colored man a nigger just to see him bow

Lord, it’s a bourgeois town

“The Bourgeois Blues,” Huddie William “Lead Belly” Ledbetter

The nation’s capital, Washington DC, as Lead Belly once sang, is a bourgeois, middle-class town of government officials, politicians and government workers. It also employs a number of people in trade and professional associations, as well as not-for-profits organizations. It has arguably given rise to a “creative class” over the last forty years, and certainly has more culture enrichment (art gallery, music, theater, dance, etc.) than before.

However, the historical roots and legacy of this city may also explain why Washington, DC, the capital of the free world, has had a smaller indigenous filmmaking community than cities like Baltimore and New York. DC has never had a strong multi-ethnic working class or a class of bohemian artists that created an ethos different from Washington’s staid middle-class.

Washington, as the nation’s capital and as the capital of the “free world,” is an anomaly. Unlike the capitals of leading developed nations — Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Russia, Japan — Washington is not the the United States’ cultural center. Washington is not considered a leading cultural center in the World Cultural Forum. As a matter of fact, Austin, due to SXSW, has more cache as a world cultural center than Washington.

“If you look at New York City as a parallel. There are people who write stories about New York and they will film it in Vancouver, but they are using New York as a character, and when you look at New York as a character it is a very rich and deep character,” Frankel argues. “It has many different layers. Look at Washington, DC geographically, it has a small footprint. It has some natural limitations and capacities to be seen in many different layers.”

That New York resonates as a strong cultural center as well as being the bastion of finance capital is due to the fact that its rise as a cultural center is based on an industry/manufacturing working class as well as bohemian niche of artists, poets, intellectuals, troublemakers, and freethinkers who could supply artististic venue with workers and potential customers in venue such as vaudeville. Cities like New York have been sites of creative artististic bohemian lifestyles and artistic creation; places of cultural cross-pollination. New York — if not the originator of certain music styles — has had several musical forms associated with it: jazz, Tin Pan Alley, doo-wop, Salsa, bugaboo, punk rock, hip-hop, etc. Detroit invented Motown. Chicago was the home of Curtis Mayfield. Pittsburgh and Philadelphia were renown for jazz and the Philly sound,” respectively. Duke Ellington and Marvin Gaye, DC natives, had to leave town to achieve their goals. DC, however, is known for go-go music; punk bands such as Bad Brains, Fugazi and Boys vs. Girls also originated in DC.

Washington DC, however, unlike New York, has never developed a lively intellectual/artistic scene. DC has not produced any noted men or women of letters. While New York had Mabel Dodge Luhan, who ran a salon as a patron of the arts in Greenwich Village during the Progressive Era, DC’s closest salon was a cluster of politicos who roomed together as a political salon on 19th Street in DC as the “House of Truth.” The luminaries were Walter Lippman, Felix Frankfurter, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Adding some much needed artistic bonhomie was sculptor Gutzon Borglum, a part-time Klan member who did the initial design for the tribute to the Confederacy at Stone Mountain; he later sculpted Mount Rushmore.

Echoing Frankel from a different angle: “DC doesn’t have a “DC life” that you can staple down and say this is what DC life is,” says DC native and DMV film advocate Anthony Greene. “If you see a movie from Chicago, it’s quintessential. If you see a movie about New York — from the eighties you see all the graffiti and all the pawn shops, and Time Square — that’s quintessential New York. DC never had that quintessential distinction.”

Courtesy Blowback Productions

PART THREE: DC’s Creative Economy and Film Industry

When Adrian Fenty, at the age of 36, became the youngest mayor of Washington, DC ever elected, he proclaimed: “We are building a world-class, inclusive city. And we are committed to doing everything to ensure the success of this dynamic sector of our economy.”

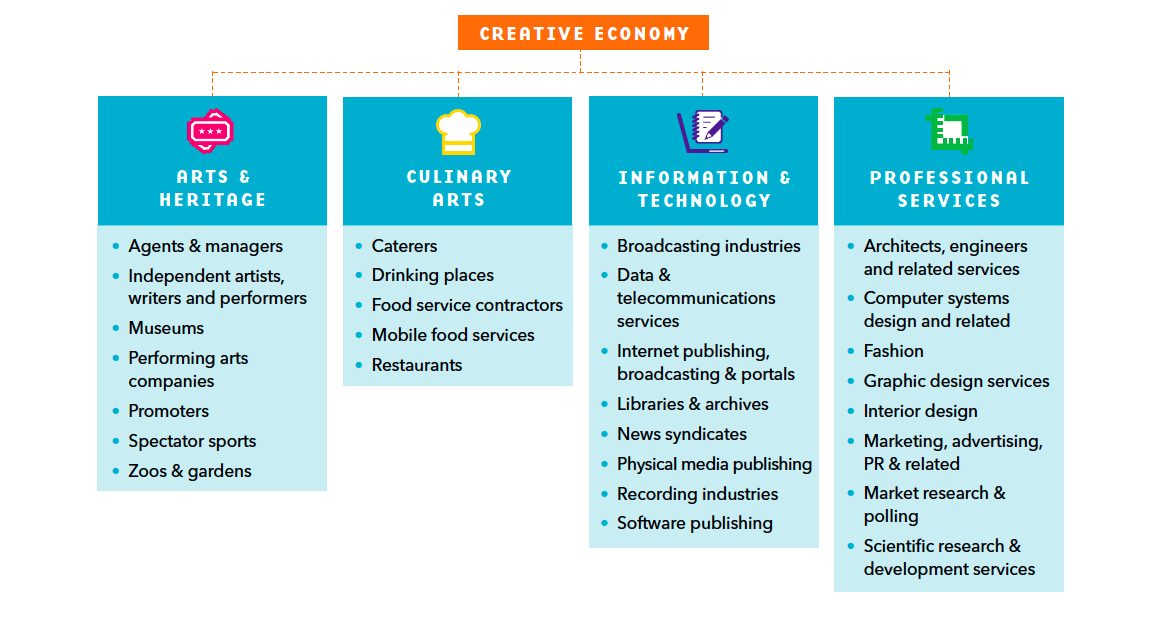

That dynamic sector of the economy was the the city’s creative economy. This creative sector refers to enterprises in which creative content, both technology and cultural forms, spurs and drives both economic and cultural values, businesses, individuals, and organizations engaged in the creative process. This sector, usually clustered around specific localities and universities, acts as a local economic engine to create a number of jobs, income and revenue for a city’s residents.

The idea of a creative economy was first articulated by Richard Florida, an economist and social scientist, who wrote the “The Rise of the Creative Class.” This “new or emergent class — or demographic segment made up of knowledge workers, intellectuals and various types of artists — ,” according to Wikipedia, “is an ascendant economic force, representing either a major shift away from traditional agriculture- or industry-based economies or a general restructuring into more complex economic hierarchies.” Florida cited national and internal locations such as Silicon Valley, Austin, Boston’s Route 128, Seattle, The Triangle in North Carolina, Bangalore, Dublin and Sweden as hot spots of the creative economy.

Florida became a guru spreading the gospel of the creative economy and a number of city officials listened, including Mayor Fenty. In May 2010 a joint initiative by the DC Office of Planning and Washington DC Economic Partnership issued Creative Capital: The Creative Action Agenda. This agenda outlined how the city’s “creative economy was “hidden in plain sight” next to “governmental enclave, tourist sites, and monuments.” The intent of the Action Agenda was to provide a blueprint for the public, private, and nonprofit sector as well as residents…”

Filmmaking was listed under Media and Communications as one of six of the agenda’s “creative segments”; the other segments were Museums and Heritage, Building Arts, Culinary Arts, Performing Arts, Visuals Arts/Craft Design Products. As seen in Table 2 Media and Communications workers comprise the largest number of employees of the DC creative economy.

This sector of workers also included editors, writers, books, software,and other forms of media. The study, however, made no attempt to distinguish those film production workers who worked on Hollywood-scaled productions from those who would be termed “independent filmmakers.” On the other hand, DC has “An emerging local specialization in documentaries that is spotlighted at SILVER DOCS, an international documentary film festival held annually in nearby Silver Spring, Maryland. DC is arguably becoming the nonfiction media center of the country, with a significant number of production companies and nonprofits that support film and video production.” But the relationship between Hollywood films and the District’s tax incentive program to attract such production and the city relationship with its own indigenous filmmakers was missing.

As matter of fact, the agenda seem to encourage documentary filmmaking more so than narrative films. The study said: “With the federal government, national associations, and major institutions such as the Smithsonian and National Geographic, there is a critical concentration of both the market and the talent needed to further grow the documentary film industry in Washington, DC.”

Once again, the documentary film community is better situated than narrative filmmaking since it is a natural component of official Washington’s politics, policies and issues matrix. In fact, after LA and NY, DC is, perhaps, the third largest film production center in the country. (A fact which led co-founders Erica Ginsberg and Adele Schmidt to create Docs in Progress, which trains DC/DMV residents in the art of documentary filmmaking.)

However it’s DC independent narrative filmmaker sector that is having birthing pangs. While it is often difficult for filmmakers anywhere to access financing for their endeavors, filmmakers in the District have reported particular barriers in obtaining loans to finance their studio space and productions. In addition, many companies in this sector need very small spaces, with considerable technology infrastructure. With limited incubator space currently available in the District, this has presented a barrier to those in the industry who would like to stay in Washington, DC.

Going through the strategy section regarding how to be innovative in creating a more advantageous investor atmosphere for filmmakers, Fenty’s Action Agenda didn’t have much to offer.

One of the major hurdles facing independent filmmaker is a lack of funding. The District will only offer 35% tax incentive to films that have a budget of $250,000 or more. The Action Agenda didn’t offer any innovative ideas to address this issue.

It may be a moot point that Mayor Fenty was unable to implement aspects of his Action Agenda since he was voted out office after one term in 2011. Trying to overhaul a moribund bureaucracy, which included the DC school system under the command of Michelle Rhee, the city had two “bad cops” trying to make a sclerotic city system do better. DC voted out the chief “bad cop,” and the other one resigned.

The Next Creative Economy Agenda: the Gray Administration

The next iteration of DC’s creative economy was under Mayor Vincent Gray who succeeded Adrian Fenty. His administration’s report, the Creative Economy Strategy for the District, had, according to City Paper, “bested” Fenty’s. It was “22 pages longer than Fenty’s, has six more mentions of millennials, and ha[d] better stock footage of scenesters in office settings.” It also, as did Fenty’s, considered the “culinary arts” as a “creative” sector.

It also dropped filmmaking as one of the creative economy sectors in DC. The only mentioning of film was the animation studio Pigmental,which was brought in by DC film office director Pierre Bagley, a veteran film producer and director.

Interestingly, while virtually no aspect of either DC’s indigenous film community or large scaled Hollywood production was factored into the Gray administration’s creative economy, the administration’s Office of Motion Picture and Television Development (OMPTD), then led by Chrystal Palmer, released, in 2013, An Analysis of the Entertainment of Media Industry in Washington, DC. The study’s key finding, provided by ECONorthwest, were: 1) DC has a substantial film industry; 2) cash incentives attract out-of-state productions; 3) such incentives overtime supported the growth of the District’s indigenous film industry; 4) the District should measure the effectiveness a film incentive through the growth in the indigenous film over a period of several years.

This study actually broke down DC’s film industry into three sectors: Out-of-state production companies based elsewhere than the District; Indigenous film and video production are DC-based companies and freelancers that produce film and videos; and Digital media production are firms that produce video for online consumption, animation, VFX, and entertainment software (i.e., games).

It also cited the actual number of jobs created the District’s indigenous film industry, in 2012, at 1,877, and this sector generated $160.9 million in labor income. However, out-state-productions (aka Hollywood-scaled films) generated 266 jobs and only $18.4 million in labor income. The analysis, however, concluded that tax incentives were beneficial to the District.

However, the 2013 testimony of Jessica Fulton, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, argued the following: “the study found that DC offered subsidies totaling $2.6 million in 2007, 2009, and 2010, but that the spending only generated tax revenues of $1.5 million. Thus, the incentive cost the District approximately $1.5 million.”

PART FOUR: The City Council is Bullish on DC Film Production But Not DC Filmmakers

The pro-incentive analysis, prompted by the District’ Office of Motion Picture and Television Development, found that tax credit incentive were beneficial to the District. Some tax policy specialists have stated otherwise, citing that such analyses are biased in favor of supporting tax credit at a state’s expense, as argued by Center for Budget and Policy Priorities’ “State Film Subsidies: Not Much Bang for Too Many Bucks.”

However Jack Evans, DC Ward 2 city councilmember disagrees. “There are tons of studies that show that movies produce nothing for a jurisdiction. When, in reality, there are studies that show they actually do.”

In an email response to the question as to why states still continue these questionable policies, CBPP senior fellow Michael Mezerov wrote:

“State policymakers are beginning to wake up to the fact that film incentive programs have been a costly boondoggle; at least a half-dozen states have repealed them. Hopefully more officials will look at the facts and take the same step. But there is a solid core of people who are inclined to believe that all tax cuts or tax incentives stimulate substantial economic activity, and they ignore or dismiss lots of research to the contrary. So it’s no surprise they’re dismissing the research on film incentives as well.”

The DC film office, now called Office of Cable Television, Film, Music, and Entertainment (OCTFME) and currently headed by Angie M. Gates, offers tax incentives (cash rebate) for large productions with budgets that begin at $250,000. “National Treasure: Book of Secrets” (2007) received $211,432 in sales tax reimbursement; “State of Play” (2009) received $183,606 in sales tax reimbursement; and “How Do You Know” (2010) received a fix grant of $2 million based expected local expenditures of $8 million.

However, since 2010 the city has not attracted any large productions. As matter of fact, the 42% tax incentive rate shrank to 35%.The OCTFME’s FY 2016 approved budget is $13,601,488. However, the proposed FY 2017 will have experienced a 12% dropped, to an operating budget of $11,964,082.

Noticing the dearth of film productions in Washington, the Council of the District of Columbia moved to rectify the Washington’s “postcard” syndrome. Councilmember Jack Evans observed that, “Washington DC used to be a place where they come to make movies. There were a lot of movies in the past where they actually filmed here,” such as “All the President’s Men” and “No Way Out.”

“[Film production] became problematic here and in many cities in the country because it became too costly. The labor cost got way out of line and other cities and places were willing to make accommodations to get film companies to go there. What Washington, D.C. has become — we call it “the postcard” — a film company will come here for a day to film the White House, the Capitol, the Monument and everything else. And they’ll go to Toronto to film the movie as if it was Washington. Or they’ll go to, of all places, Baltimore, which has become much more welcoming and film the movie.”

For a die-hard Bruce Willis fan who likes Willis’ “Die Hard” series, nothing inflamed Evans more so than seeing supposedly a shot of DC’s 14th Street in a “Die Hard” production filmed in Baltimore. Evans cited other examples of faux Washington locations being passed off as authentic DC sites in television shows like “West Wing.” “It was just postcard shots and they filmed the rest in a studio in Los Angeles.

“And you can go up to the one that drives me completely crazy, House of Cards,” said the annoyed councilman. “We had an opportunity to bid on House of Cards and we didn’t, and Martin O’Malley did. So, House of Cards was filmed in a giant studio in Maryland, right outside of Baltimore.”

This missed “opportunity,” and others like “Veep” and “Lincoln” (filmed in the capital of the Confederacy, Richmond), seem to have been the tripwire that prompted the concerns of some DC council members: films were being made about Washington but the city wasn’t getting any of the gravy from large-scale production monies. “You have to get in the game,” said Evans.

Evans and fellow councilman Vincent Orange set up a dedicated fund to provide tax incentives to the film productions, which subsidizes the production, paying the production to film in a locality, which offsets the labor cost of production. The DC Council has finalized the DC Film, Television and Entertainment Rebated Fund 2017 budget at $4.3 million.

Vincent Orange, now the president and CEO of DC Chamber of Commerce, was the chairman of the council’s Business, Consumers and Regulatory Affairs, also took a keen interest in the lack of DC’s film production. “In that role of chairman and working with Mayor Bowser, we established the Office of Cable Television, Film, Music, and Entertainment,” says Orange. “That office was established to go in a certain direction and let everyone know that the city was open for film production.”

Orange, like Evans, cited that film productions were occurring in Maryland and Virginia, but not in DC despite the productions’ storyline being in the nation’s capital. He, too, found Washington’s “postcard” syndrome too much.

“A number of those productions that were taking place would come into the city and shoot our monuments and a few other things, and go back to [other places, like Maryland or Virginia] and shoot them as if they were in Washington, DC.”

When Orange and other city officials visited Hollywood studios three, four years ago there was a list of four items that studio executives brought to their attention. They were told that the city lacked a soundstage, and since that time DC has acquired access to BET’s soundstage via a “marketing partnership” with BET (which means the city tells producers about the existence of BET and nothing more). The second item was DC tax incentive fund.

“It had a great fund on paper,” says Orange, “but it was not not being funded. It needed a steady funding source to compete with the other markets.” Hollywood wants to see “certainty” and a tax fund that lacked a dedicated amount announced a lack thereof. A third concern was the availability of local crews who didn’t need to access Washington’s hotel, “but could go home and sleep in their own beds as opposed to running up hotel costs.”

And the fourth item, for which Washington is infamously known, is permits; several jurisdictional gods have to be appeased in order to get a permit to film in the District.

“In the District of Columbia, DC controls the streets; the Secret Service controls the sidewalks; the Park service controls all the parks; and then a new player came into play, the Capitol Police,” the former councilman outlined. “So what [producers] were looking for was one-stop shopping. Just one place where they can go. Basically a clearinghouse where you can go to one location to get the permits.”

Orange cited those four items as the main “obstacles” to reigniting productions in Washington DC. Orange decamped the council to lead DC Chamber of Commerce. Evans remains on the council, however, and believes there is a window of opportunity to get everyone on board to resolve the issues of funding, and having ‘one-stop shopping’ to solve the cross-jurisdictional discussions about ways to coordinate the chaos of DC’s confusing film permit situation.

He cited Angie Gates, the director of the DC film office (aka OCTFME), as the kind of leadership that could solve the two most pressing issues. (Several attempts were made to contact OCTFME for this article; the writer was only able to verify a few items on “background.”)

Yet the film and TV productions cited by Evans —”All the President’s Men,” “No Way Out, Veep,” “House of Cards” — have, to varying degrees — an anti-Washington theme. Indigenously produced films or TV shows about the good, the bad, and ugly — the community of residents regarding DC? That seems to be an afterthought of the city council.

“I don’t know that we do,” Evans admitted regarding an agenda to spur local filmmaking. “But that is a great suggestion. How do we get filmmakers to film local stories? I don’t have an answer and I think that is a great suggestion to do.” Evans than mused that perhaps this is something that a “government agency, so to speak” would do to help promote that.

One DC filmmaker suggested that perhaps the city support a private-public, city-business film competition would award $50,000 or more to the best low-budget, independent short or feature film to spur filmmaking, the councilmember seemed receptive to the idea.

“Absolutely. I think that’s a great idea,” said Evans.

When Vincent Orange was asked about the status of DC’s smaller, indigenous filmmaker, it was his understanding that “Angie Gates had provided some funding to a number of smaller productions.”

Once again, neither Ms. Gates nor the film office was available for comment. However, another name that Orange mentioned, and which constantly came up regarding local DC stories and indigenous filmmaking, was George Pelecanos.

The Mysterious Mr. Pelecanos

While George Pelecanos’ name came up numerous times when discussing filmmaking in DC as a source for this article, he did not want to go on the record discussing filmmaking in DC. The author of several novels about the life of crime and mystery in DC, Pelecanos is in the process of dealing with the District of Columbia as the producer of a forthcoming project. If he is, in fact, dealing with the city that would mean like any producer, he is probably dealing with the city’s byzantine permit jurisdictions and may be trying to apply for — surprise! — a tax subsidy.

Like any talented creative son or daughter of DC, he’s had to leave DC (ever heard of Taraji P. Henson?) to make his mark in films and TV. He’s written for the celebrated HBO series “The Wire” and “Treme,” and wrote and produce “The Confidential Informant” (2015).

Pierre Bagley, the Gray administration’s former director of OMPTD (OCTFME’s predecessor) and a film producer, met Pelecanos when he began a series of introductory meetings as the city’s newest go-to-film guy. When Pelecanos approached Bagley, querying him about what “he was doing to make an industry in DC., Bagley, replied asked him, “George, why are you leaving DC?”

For a veteran film producer and director such as Bagley, filmmaking rest on three things, as a three legged stool. “It’s content which is the story you like or develop or books. It’s financing, and its distribution. Now people can say it’s a thousand other things, but at the end of the day when you talk about sustainability, without content, without financing, and without distribution, you have something else.”

Bagley cited Pelecanos as an example of a three-legged stool predicament. Pelecanos has made the transition from being a DC writer to writer/producer/director — outside of DC. But Bagley’s point is that Pelecanos still had to go outside of DC to get his films made because DC itself provides no indigenous financing or structure to get District stories told. As a matter of fact, if Pelecanos cannot obtain tax incentive from the city, it is likely that he will not be able to make a DC-based project if he’s also seeking funding from Hollywood.

When questioned about how comparable cities were able to produce well-known directors or celebrated films about certain cities but not DC, author and film Mike Canning replied, “It’s not required. There are a lot of other cities — Chicago doesn’t have that filmmaker, neither or Detroit or San Francisco… It isn’t required obviously. It takes a singular talent, and it takes a singular talent who stays there.”

Bagley has a different take: “If you look at Spike Lee, all of his films were Brooklyn-centric for a very long time. You look at Martin Scorsese his films were New York-centric for a very long time. Woody Allen. They made films about the environment they were in. What was different between them and a DC filmmaker is that they were in a sustainable part of the country where there is a filmmaking community.”

A DC Film Community?

Does Washington have a filmmaking community? According to the DC film office 2013 report, there’s an “indigenous film industry,” but is it a filmmaking community?

“For me I’ve found it to be very supportive, at least the narrative scene,” says Shoshana Rosenbaum, director of “The Goblin Baby.” “It’s not very big here. There are a lot more people doing documentary work and because of that there are a lot people who have the skills to do the narrative work, and when a project comes along they seem to be excited and supportive about it.”

Russell Max Simon, the founder of 7K Films and director of “Districtland,” a TV pilot, and #humbled, a film, however thinks the idea of a DC film community isn’t as solid as elsewhere. When asked about the status of independent filmmaking in DC:

“Unfortunately I think the status is virtually nonexistent. There is clearly not a community here like you would find in Austin or you would find in Atlanta. I think that is pretty incontrovertible. That said, there are filmmakers here; there are plenty of filmmakers here.”

The depth of narrative filmmaking is boxed out, once again, by documentary filmmaking in the District. As stated before, the city itself trends toward documentary because of the near death-grip of official Washington’s politics, policies and issues matrix on the city, and the perception of it as nothing but politics 24/7.

“There are filmmakers in DC interested in indie filmmaking, narrative filmmaking, just like you would find in any city,” says Simon. “But I think there are a few problems that are all coming together by way of explanation. It’s not going to be just one thing.”

Simon cited what he believes are few issues stymieing DC’s indigenous film scene. Lack of a single individual or crucial individuals rallying the film community. While Richard Linklater and Robert Rodriguez put Austin on the map as filmmakers, they were also boosted.

“Every filmmaker I know who talks about what happened would mention Linklater not just as an example of someone who inspired them but someone who helped tie the community together. Who showed up at events. Supported events, who really helped the community to grow. So, we don’t have someone like that here, adds Simon.”

While DC and the DC area (aka the DMV) are abundant in numerous film festivals, their impact are limited unlike the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). “We have plenty of festivals and I have been involved in a couple of them, but they just are not big enough or well known enough that people start looking at DMV and thinking to themselves,‘ Oh, that place is crawling with creative talent.’ ”

In other words, DC has no version of a SXSW that ties together the various strains or realms of DC: film, technology, entrepreneurial start-ups, etc. — the very elements of a creative economy. Simon also cited the bread of butter of modern filmmaking tax credits as a problem. They really don’t mean much to independent filmmakers since they can’t make the initial threshold of $250,000.

“Obviously somewhat like me would love to get a tax credit for a fifty thousand dollar movie, but that doesn’t make sense from the state’s point of view. From the state’s point of view I’m already going to make my movie here; it’s not worth giving a tax credit to a low budget film.”

While there is a pro and con debate regarding the efficacy of tax credits, Simon believes what they do is grow the film production crew workforce with stability, which may make skilled professionals secure enough to lower their rates for an independent production. “I may want to hire a crew to go make a movie and they really know what they are doing because there are larger budget productions here. So, it does overflow to some extent.”

At the other end of the DC film community spectrum are organizations such as Women in Films and Video (WIFV), which is more ecumenical than it sounds. Led by executive director Melissa Houghton, WIFV has been at the forefront of offering professional preparation to aspiring DC filmmakers.

Washington “has always been known as a nonfiction media center, but in the last five years in particular I’ve seen a lot of growth in the narrative section, whether it is short or feature length.”

Increasingly, as Houghton pointed out, DC has a “ton of screenwriters” as well as “good actors” and “more and more producers and director trying to figure out how to make here on budget.”

One of the developmental strategy of WIFV-aspiring filmmakers is to first produce to scripts. “They can write without financing; they are really trying to hone those skills,” informs Houghton. WIFV also stages a “Director’s Narrative Roundtable.” The idea behind the roundtable is to acquire the knowledge and skills that needed to direct a screenwriter’s own script if that opportunity arises. If they have directed a short film they could well be on their way to doing a feature film.

For WIFV, this moment is now a period of creative fermentation in DC. “What I’m loving right now is that everybody is trying to figure out what they don’t know, and how to build that expertise. No one [outside of DC] thinks there’s a creative community at all. There’s a very creative community here. They just don’t look.”

“I’ve been a member of [WIFV] for a number of years, and they have been very instrumental and really encouraging of people like me,” offers Rosenbaum about the organization. ”This is not a first or second career, but following an artistic pursuit while like most people with a day job, a family and children and all that.”

As well as ScriptDC and other numerous roundtables looking at the technical/creative aspects of film production, WIFV also host a Film Financing Roundtable that featured Ari Pinchot of Crystal City Entertainment and Marina Martins of Pigmental Studios (Martins, whose studio was brought to DC during Pierre Bagley’s tenure at DC’s OMPTD, recently achieved major financial backing from international investors).

Examining the process of acquiring for film financing is even more a key, elemental component for small independent filmmakers in DC since District agencies don’t have an expansive vision regarding its own indigenous independent filmmaking industry.

“There’s not a culture here yet of funding independent films. The DC Humanities Council can fund a non-fiction piece, but they don’t really have the capacity to fund fictional work,” says Houghton. “The DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities have given some writers funding to write their screenplays, but I don’t think they have ever funded a narrative work in media; it’s not in their wheelhouse yet.”

The DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, stated the following regarding film: “Filmmakers are eligible to apply to our Artist Fellowship Program grant (AFP) or our City Arts Projects grant (CAP) for individuals. AFP provides general operating support to individual artists, while CAP is tied to a specific project.”

Dogma DC: “No White House! No Capitol! No Monuments!”

Independent filmmaking in DC is problematic because of primarily two things: 1) lack of vision by the city leaders to consider the possibility that an industry exist under the city’s feet. The city is wedded to the idea that the only films worth funding are large-scaled Hollywood films that tend to encourage negative views re official Washington and occluded any perception of DC as a place where people live.

City agencies — the city council, the mayor’s film office, the arts agencies — offer limited support to DC’s indigenous film community as producers of films about the good, the bad, and the ugly of DC. The DC film office didn’t even think to show the films, trailers, or highlight reels of its noted Filmmaker of the Month on the city’s digital venues. However, next year, according to a source, this will be rectified by future OTMs receiving video-biographies and some of their work shown on DCN. Yet, once again, that OCTFME doesn’t have one dedicated office within OCTFME dealing with local film issues should produce a “huh?”

Funding films is a risky business and, once again, the DC government does little to fund local DC filmmakers. It could inexpensively do so by setting aside a dedicated film fund of $1 million to award the best films set in DC. The winner would receive a $50,000 to $100,000 cash award. This would be awarded for each year over a 10-year period. If DC hasn’t generated a class of worthy films or filmmakers then, then let ’em make docs. After all, this is the city were “culinary arts” are more prized than filmmaking.

Given that DC and the DMV, is awashed in money — new technology money — the city has no patron or patrons who have the civic thought of wanting to make DC as cool as New York or Austin.Once again, DC’s heritage as a political, policy, and issue matrix, blocks the residents from seeing the city as a matrix of film, technology and entrepreneurial start-ups.

“I think in some ways it is a chicken and an egg problem. If more stuff were coming out of here, more people would think to do it. Nothing is coming out here. No one is thinking to do it,” says Simon. “There’s a joke that dentists invest in independent films, but it doesn’t take that much to make independent films nowaday. I wish that some brilliant producer would come along and fund a hundred, two hundred filmmakers. It’s not that they are not here; it’s a rich area.”

Yes, DC is a rich area; it’s been called recession proof. However, it also has had a history of making thing happen when they hadn’t happened before. DC needs an independent film movement with a vision. It needs to follow the legacy of a scrappy DC gal, Zelda Fichandler, who, while creating the Arena Stage (the first racially integrated theater in the District) became the godmother of the regional theater movement. Today, DC is cited as having the largest number of theaters outside of New York itself. Zelda Fichandler is the model for DC film “Independistas,” and the city should be handing out a “Zelda” of $100,000 to the best films about life in DC over the next ten years. Films with no White House, no Capitol, and no monuments.

Norman Kelley’s last film was “How Washington Really Works: Charlie Peters and the Washington Monthly.” He’s currently raising funds to produce The Darker the Berry, a film about colorism set in DC.