Question: You had a pretty bourgeois and comfortable childhood, in Birmingham; and so did your sister [Angela]; can you trace the development of someone from that kind of background into a revolutionary and Marxist person?

Fania Davis: I see in her life, the makings of a revolutionary, not a tragedy. From her time in the south (Birmingham) to her experience with white people in the north, Angela’s education is now being put into practice.

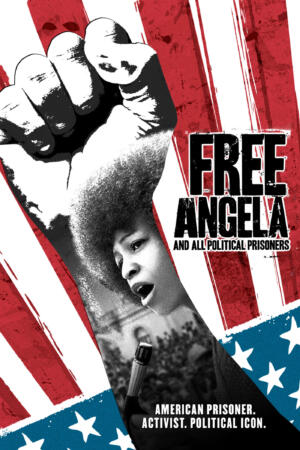

A conversation between a journalist and Angela Davis’ sister, Fania Davis, from a scene about mid-way through Shola Lynch’s no-frills, candid feature documentary “Free Angela & All Political Prisoners,” soon after Angela’s arrest and initial confinement, following 2 months on-the-run with the FBI in chase.

This specific interview block really sums up “Free Angela”; attempts to discredit her, countered with statements and actions that honored who she had become – an activist, an intellectual, an inspiration, a fearless leader, a communist, an African American, a woman.

For those in power, all those elements combined together in one being spelled “Dangerous;” hence the political conspiracy to ensure that Davis was imprisoned and be eventually put to death.

Fania’s reply immediately made me think of Sam Greenlee’s incendiary “The Spook Who Sat By The Door,” with Dan Freeman, the “spook,” educated under/within a system built and controlled primarily by whites, using their tools to master, inform and enlighten himself, and later turning against that very same system, utilizing that same acquired mastery to inform, educate, enlighten, and inspire others – primarily those oppressed – to revolution.

Not to suggest that Angela’s motivations were so meticulously thought out and planned as were Dan Freeman’s, from the first time she was introduced to the then burgeoning youth movements calling for revolution. But like some young revolutionaries of the time, who may not have had any idea of just how bloody a real revolution can really be, allow me to romanticize the possibilities.

In October 1970, Davis was arrested in New York City in connection with a shootout that occurred on August 7 in a San Raphael, California courtroom. She was accused of supplying weapons to Jonathan Jackson, who burst into the courtroom in a bid to free inmates on trial there (the Soledad Brothers) and take hostages whom he hoped to exchange for his brother George Jackson, a black *radical* imprisoned at San Quentin Prison. In the subsequent shoot-out with police, Jonathan Jackson was killed, along with Judge Harold Haley and two inmates. Davis, who had championed the cause of organizing black prisoners and was friends (later became involved) with George Jackson, was indicted in the crime, because the guns used in the shoot-out were registered to her; but she went into hiding, becoming one of the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s most wanted criminals; she was apprehended only two months later. Her trial drew international attention. Eventually, after about 18 months since her capture in June 1972, she was acquitted of all charges.

Shola Lynch’s “Free Angela & All Political Prisoners” relives those eventful, uncertain, transformative early years of Angela Davis’ life; it wants to raise awareness and reignite discussion on the movement she joined and eventually led, by introducing it to a new, younger generation in a simple, straight-forward, accessible style.

The title says it all – “Free Angela & All Political Prisoners.” It announces its intent immediately. You know what its POV is; it’s not a retrial of Angela Davis on film – that’s not the film’s intent; rather it tells the story of an injustice done to a young woman whose life changed completely, radically and swiftly, after being thrust into the spotlight when then Governor of California, Ronald Reagan, insisted on having her barred from teaching at any university in the State of California due to her membership in the Communist Party; a young woman who would become a scapegoat/example for the government’s (then under Nixon’s presidency) intolerance for radicalism, the embodiment of a constructed imaginary enemy; a young woman who would soon become the prime spokes-person for the freedom of all political prisoners.

But as she herself noted in the film, despite what seemed like insurmountable obstacles at the time, the revolution was right around the corner and they saw it as their responsibility to usher it in.

After a brief introduction to Davis, the film doesn’t waste much time diving right into its main narrative; Covering a trial that occupied almost 2 years of her life, from August 1970 when she went underground, after she learned she would be implicated in the Marin County Courthouse incident (leading to her being only the 3rd woman to be put on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted Fugitives list), to her acquittal in June 1972, there’s enough material here for an HBO mini-series, telling this particular riveting story, with its wealth of characters, and subplots:

– Davis’ early involvement with the Black Panther Party

– The Soledad Brothers case, and Davis’ decision to make it her cause

– Davis’ relationship with George Jackson

– The Marin County Courthouse incident itself

– Davis on the run, underground, and eventual capture

– Davis’ trial

– The zeitgeist of the period, notably what was a burgeoning anti-government movement, otherwise deemed as radicalism, after the deaths of MLK, RFK, the rise of the Black Panther Party, anti-Vietnam war sentiment, the Watts riots, etc

– Some 10 years after the second Red Scare (aka McCarthyism), COINTELPRO and J. Edgar Hoover’s attempts to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” groups and individuals that the FBI deemed subversive, including communist and socialist organizations, organizations and individuals associated with the civil rights movement, black nationalist groups, and more.

– The worldwide movement in support of Angela’s freedom.

– And even the nameless/faceless boys and girls, men and women, who may have only just then learned about, and then were inspired by this 28-year-old black woman (when she was acquitted), during those 2 years.

And more… however, there’s only so much one can squeeze into a 97-minute documentary.

It’s not an Angela Davis biography, so don’t expect a retelling of her entire life story. The film’s focus is primarily on the aforementioned transformative 2-year period of Davis’ rather eventful life.

But it does a sufficient job of giving the audience a sense of the setting, the era, the key figures involved, whether directly or indirectly, and all the central elements that contributed in some way to the film’s main focus. You get a good sense of the uncertainty and paranoia that plagued the country at the time.

Footage includes photos, as well as archival tape and present-day interviews with Davis herself of course, her sister, mother, attorneys representing her during the trial, journalists, Black Panther party members, and more.

Recorded audio of Nixon repulsed by Davis’ acquittal, seemingly assured of her guilt, labeling her a terrorist, was especially chilling.

Watching a mid-20s, seemingly self-assured, brilliant and articulate Angela Davis giving magnificent rousing speeches, ushering in what was felt to be imminent revolution, were invigorating, and, at times, elicited an impulsive applause in acknowledgment from this viewer; but were also sobering, as I remembered where I was, and what I was doing at that age, not-so-long ago, which certainly wasn’t leading revolutions.

Recreated scenes shot by Bradford Young help visualize parts of the narrative for which no archival footage exists, as those sequences, as well as archival footage of relevant American cities during those years, help keep the senses stimulated.

All those still and moving images are complimented effectively with a form- and content-enhancing soundtrack – notably, early on, with music from the fiery “We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite” album by Max Roach, with Abbey Lincoln on vocals; an album that was profoundly described as, “a record of transgressions against that body; of the anger, the hate, the sorrow, the dirt and the hope that body has known for four hundred years…”

Fitting in this case, I thought.

“Free Angela & All Political Prisoners” moves along briskly, touching on such matters of importance at the time like structural racism, the Vietnam war, rapidly rising levels of incarceration (“The Prison Industrial Complex” that eventually became a cause Davis took up), government accountability, while simultaneously working to provide an education for subsequent generations and some insight into where, in the grand scheme of things, America and Americans stand (or are headed) collectively today.

It took a worldwide movement of people to acquit Angela Davis but, in the end, that an all-white jury acquitted a young black radical/revolutionary in the early 1970s on all charges against her, despite unrelenting attempts by the government to discredit and vilify her is astonishing, if not hopeful.

Marking the 40th anniversary of Davis’ full acquittal, “Free Angela & All Political Prisoners,” likely won’t teach much new to those already familiar with Davis’ history, as well as that of the movement she was a part of. As already suggested, the film is more of a primer for the uninitiated and will introduce Davis and her engaged life to a new generation.

Although even for the initiated, it could serve as a reminder and further act as newfound inspiration, and even a call to action, capable of inciting new generations to similar acts of collective radicalism, all in the name of progressive change.

As Davis herself said in a recent interview on her reasons for wanting to have this film made:

“I was most interested in the film being made because I thought that it would not only capture me as a person, and it’s important that people recognize that figures that are media-produced are very different in their own lives. But what was also important to me was that people understood the power of the movement that emerged… What I’ve discovered is that many people who are around my age, a little younger, a little older . . . who experienced that moment, look back with this very interesting nostalgia and I came to recognize that they’re thinking about themselves, they’re remembering their own youth and they’re remembering all of the possibilities and potential and the creativity. That was created not by me, but it was created by the movement that came together around my case.”

Indeed.

The film’s scant 97-minute running time will leave you wanting even more.

It’s on various home video platforms, including DVD & Digital Download to rent or buy. You might also find it streaming online, so check it out.

Watch the film’s trailer below: