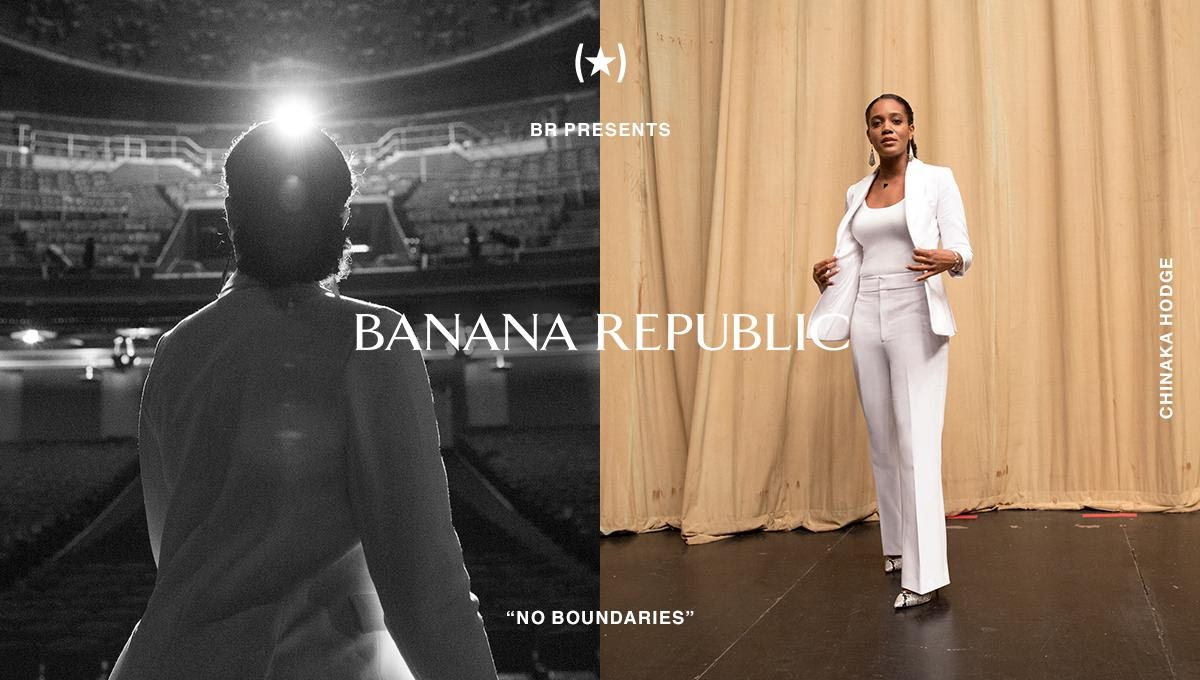

There's power in words and Chinaka Hodge combines poetry, writing and performance art as a form of expression to inspire women and ignite change.

This Black History Month we are celebrating her craft and dedication of creating a powerful space for women to dream, be bold and unstoppable. Hodge spoke with CEO of Blavity, Morgan DeBaun about how she lives her life with no boundaries and how it manifests as her unique voice and art. She also shares how black artists have made space for her to cultivate her talent throughout her life.

Read on to learn how Hodge inspires us all to live on our own terms, unapologetically.

In partnership with Banana Republic. This interview has been arranged and edited for clarity.

Morgan: Can you tell us about your journey and how you got to where you are today in your art/career?

Hodge: I got to this point in my art and career because black artists invested in me along the way. I consider both of my parents artists and they poured into me. They surrounded me with art and artistic opportunities. I did every school play, dance ensemble, gymnastics performance, recitation of scripture or text that was available. I thought I wanted to model for a bit. And my mom was my manager — she took me to auditions, call backs and shoots.

My dad’s friend Opal Palmer Adisa, the renowned novelist and children’s book writer read me bedtime stories as a child. Her mentee, Ifetayo Lawson, took me with them when they did readings at bookstores and libraries. I was still a small child. At age 15, I found a community of writers and performers in the competitive/slam poetry world. I competed for a bit — but learned I really love writing for others as I worked with Marc Bamuthi Joseph on his play, Scourge. I really found my voice when Kamilah Forbes, who now runs The Apollo, invested in me. Her mentor, the incredible Stan Lathan, gave me my first job in the entertainment industry.

My big break into Hollywood came because Ryan Coogler reached back for me. And because Tiffany Smith-Anoa’i believed both in me and in second chances. Charles King told me I was worth it. Issa Rae always shares words of encouragement. I am buoyed, even now, by my work with Rodney Barnes. I say all this to acknowledge, and to say publicly, my career is because black people made space for me to work. That is my greatest education, so far. My career goal — the only one — is to work in such a way that there is more space for my people to thrive. Not just when I die or vacate my post for the next generation. But now. I want to work in a way that the tiny apertures I walk through become full on pathways for my folks to enter as well. Right now.

Morgan: Tell us how you create your art and live without limits personally.

Hodge: I smile unrelentingly at perfect strangers. I sing in elevators. I dance at the grocery store. I poem when I want to. I offer opinions and report backs from the other side. I aim to keep horrible stereotypes about women, black people and black women off the air.

I make one mean family dinner. I invite unlikely guests.

I write poems to make women feel great about themselves. I write poems to make oppressors think twice.

I create my art in public, at the last minute and under heavy stress. I create my art alone, with lots of time and in my best calm. I create when I must.

Morgan: How has fashion influenced your expression of self and how would you encourage others to find their sense of a signature style?

Hodge: I am a survivor of sexual assault and abuse at a very young age. For a long time, I tried to hide my body. I wore oversized coats, big pants, large hats — fairly unaware how hard I was attempting to hide. As I tackle my own self-assuredness, I have begun to express my sensuality, my power, my politics and my history in my daily attire. For the better part of the last decade, I have worn black on stage for all of my performances as a response to the unjust killings of black men.

But in the last year I have gotten back into color, gotten into more form-fitting clothes, released my hair from under all of these hats. I am delighted to find that there is still a person under all this armor and am choosing clothes that better express my moods — the happy, the frustrated and the joyous emotions — are all coming out in my clothes.

I’d encourage others to put on clothes that have a purpose, your literal happy pants — clothes for grieving — “first day of” clothes. I have come to imbue my wardrobe with these meanings and it helps to facilitate my own emotions flowing more freely.

Morgan: How do you feel like you are breaking boundaries through your work?

Hodge: These days, a lot of what I write for television is genre: a lot of science fiction and magical realism. A forthcoming project that is very special to me features young black girls in a supernatural world. When I was growing up, the field didn't have a whole lot of books or TV that situated black girls as truly gifted. I think Octavia Butler birthed a generation of writers who get to break larger boundaries because of the walls she knocked down first. Now, there is a widening range of black Sci-Fi, spec-fi and magic realism in literature, cinema and television — black characters with black female creators. I am proud to be a part of that cadre of writers.

Morgan: Why do you find it important to live life on your own terms as a Black artist?

Hodge: I'd like to get to the level of success and stability that allows me to live “on my own terms.” I really don't want to be famous or rich — mostly I want to be able to have choice — meaning options, mobility, access, — that allows me to see the world, say what is true to me and create pathways to success for my loved ones.

Morgan: What advice do you give Black Millennials who are in a traditional career path but want to transition into creative/freelance career path?

Hodge: First, I’d ask what is working about your traditional career? What about it attracted you in the first place. Routine? Money? Respect from your family? I’d ask myself if those things are important. And I’d be honest. Because my next question is what can you take from your more traditional gig into your freelance life? Is it rigor around paperwork? Is it performance review or self-assessment? Is it a convivial workplace with other creatives around, who inspire you?

I’d advise you to plan your exit being mindful about what you may take for granted in your current set-up. Gym time? Office supplies?

And then I would design the freelance/creative path that retains as much of your current joy/success/income as possible. You’ve already spent this time making a name for yourself in your current lane. Can you port some of that clout with you as you leave? Are there relationships or habits you’ve built that will serve you in your next life?

Can you scaffold your switch? Meaning, can you [scaled down from your] work from 80 percent to 20 percent for six months? Then [work] 50/50 for a while? Will making a slow shift benefit you?

My last piece of advice is find a person or a group of people who are working to change their lives in drastic ways. Check in with them as you go. Accountability and a plan change a wish into a goal and a goal into an outcome.

Morgan: What does it mean to you to be a Black visionary/artist?

Hodge: I have been thinking about this a lot. A buddy of mine, who is a well-known black creator and tastemaker, called himself a visionary in casual conversation. The same way one would if he said he were a painter or a theologian. It was a matter of fact, not a matter of opinion or acclaim, which is how I used to think about the title of visionary. More and more, for me, being a visionary is about the process by which I make. As a practicing visionary, I try to imagine what the future needs and wants, and then to create that. It is a very different generative place than trying to make what is hot now, or what documents what once was. I think the role of the artist is to be all three — a historian, a documentarian and a visionary. Someone who wields the past, and applies it in the present, in the interest of the future.

Morgan: Why do you think it’s important to celebrate Black visionaries and artists during Black History Month — both past and present?

Hodge: I think it is important to celebrate black visionaries and artists every day. I think the Negro History Week that Carter G. Woodson championed should naturally blossom into what it could be. A primacy put on pride in one's own heritage lends itself to a full out appreciation for the works and cultures of all people. That said, I love a holiday. I love observance. So in February, I remind myself to do what I should be doing most days — buying goods, art, service and education from black people. Building institutions that honor our history. Building legacies for the next generation to inherit.

Morgan: How can Black Millennials pay homage to our ancestors? Do you think sharing our true gifts and talents is making a significant difference in leaving a legacy for our generation?

Hodge: I believe our ancestors worked for us to have choice. The more we take on career paths and ideas that were previously put out of our reach — the more we say yes to risk — the more our heirs stand to inherit. We are supposed to be innovative, bold and confrontational. We honor our ancestors by using their tools and employing them in new as well as tried-and-true modes.

Morgan: What do you want the world to take from the work that you do?

Hodge: I think the core of what I am put on earth to do is to connect others. Poems and screenplay are the most front-facing tactics — but really my work is to put good people into conversation. It is to make the commonplace feel new, disrupted or outdated. I want people to see or hear my work and want to talk to someone else about it, and then for that conversation to be so compelling that they forget about me entirely.

Morgan: How does it feel to inspire other Black creatives to use their talents to make the world a better place?

Hodge: I hope I do. I hope inspiration is a by-product. Inspiring others is never my goal. I tend to fail when it is. But I hope that what I do adds light, weight or value to the world. I hope, if a blueprint is needed, that something I have done helps those near or behind me to plan.

Art is in Hodge’s blood and she wants to make it her mission to inspire the future generations of women to know that they’re unstoppable and their potential is limitless. Creating opportunities and safe spaces to flourish can help women’s dreams be achievable. Their voices are the force to drive the culture through.

Check out how Hodge expresses her full self with no inhibitions below.

Learn more about how Banana Republic is honoring Black History Month and shop the Bold Vision collection.