Legendary actor Sidney Poitier died last week at age 94. Poitier was a groundbreaking star, giving peerless performances, including his 1963 starring role in Lilies of the Field, for which he became the first Black man to win an Academy Award for best actor. Poitier was also a civil rights icon, supporting Black rights and acting as a friend and fundraiser for many of the movement’s most important figures; Martin Luther King Jr. once lauded him as “a man of great depth, a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom."

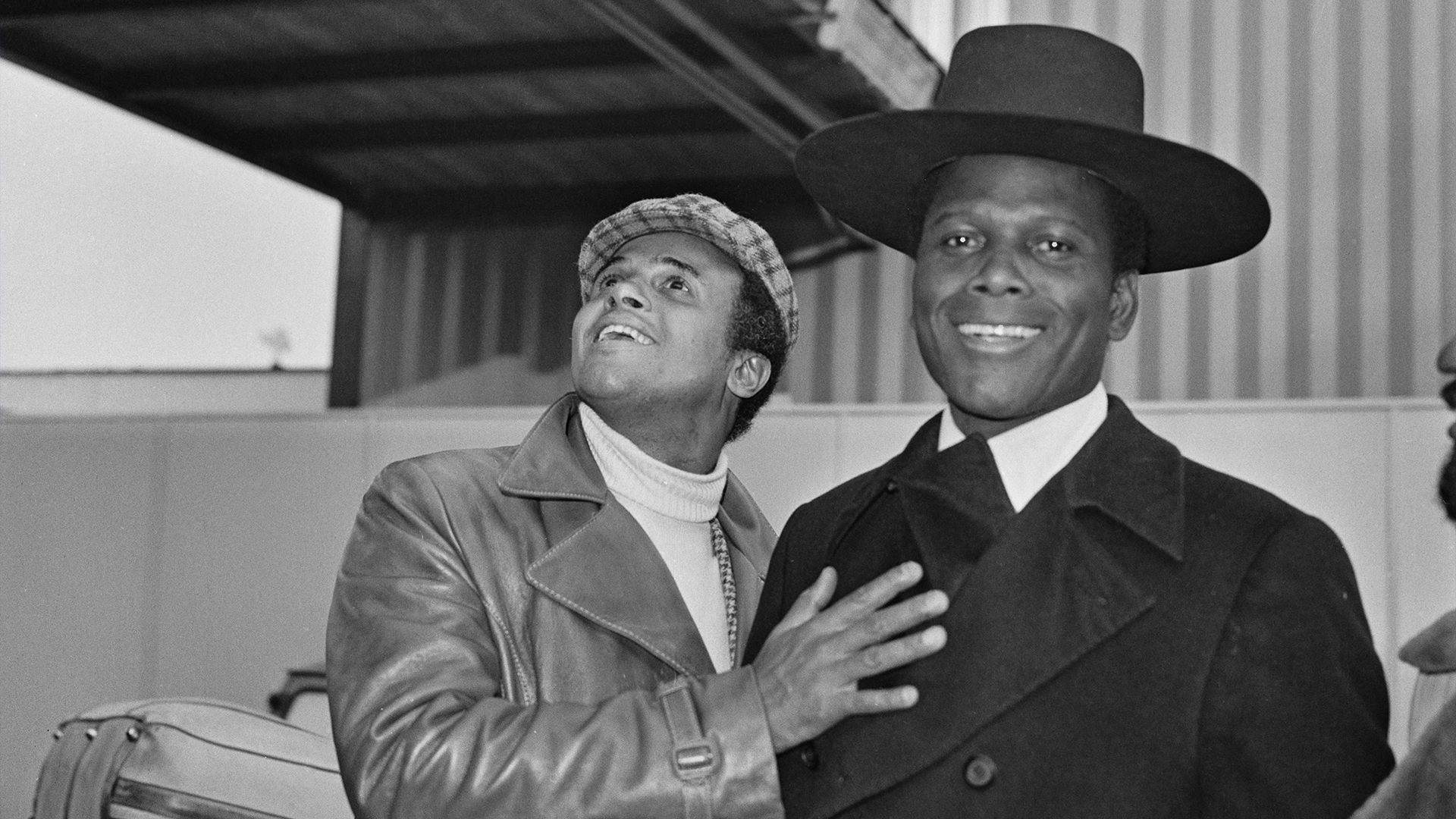

As stories about Poitier proliferated on social media after his death, one particular anecdote stood out. Several people, including journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, recounted a tale of Poitier and his best friend, Harry Belafonte, flying to Mississippi and escaping the Ku Klux Klan in order to deliver thousands of dollars to the organizers of the Freedom Summer to keep the campaign going.

Many of you know Sidney Poitier as the barrier-breaking actor. But at his core, he was a RACE MAN. A few years ago I interviewed a veteran of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement and he told me this amazing story about Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte and Freedom Summer.

— Ida Bae Wells (@nhannahjones) January 7, 2022

Taking place during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer was one of the signature campaigns of the movement. To counteract the especially violent and widespread suppression of Black voters in Mississippi, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and other organizations trained a thousand volunteers, mostly Northern white college students, and sent them to Mississippi to work with local Black activists to register Black voters in the state.

As the campaign was short on funds by August, famed entertainer and activist Harry Belafonte raised $70,000 and called up his friend Poitier to accompany him to Mississippi to deliver the cash. By this point, Poitier and Belafonte were well into their lifelong friendship and had engaged in various civil rights causes, including attending the 1963 March on Washington together. Belafonte was worried that he would be met with violence in Mississippi. He figured that the presence of two of America’s most famous Black men — Belafonte was a top-selling recording artist at the time and Poitier had won his Oscar only four months earlier — might make an attack less likely than if he went alone.

The two men had plenty of reasons to be worried. Historically, Mississippi had been a particularly dangerous place for Black people and those who supported Black rights; more lynchings took place in Mississippi than in any other state. Three young Freedom Summer workers — James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner — were murdered in June 1964.

Poitier agreed to go with Belafonte and the two flew to Mississippi, where they were greeted by local SNCC activists. As they left the airport together in a car that night, with Poitier and Belafonte in the backseat, local KKK members began chasing their vehicle. At several points, a pickup truck with a wooden plank attached to its front bumper repeatedly attempted to ram their car off the road. Eventually, a convoy of SNCC vehicles showed up to escort them safely to the Black portion of Greenwood, Mississippi, where they met up with SNCC activists.

One report of the evening said that Poitier was deeply moved by the welcome they received in Greenwood. Poitier reportedly remarked to the people gathered, “I am 37 years old. I have been a lonely man all my life. I have been lonely because I have not found love, but this room is overflowing with it.” He then turned to his friend Belafonte, who led the crowd in a rendition of his famous song “Banana Boat,” transforming the famous “Day- o, Day- o, daylight come an’ me wan’ go home” lyrics to “freedom, freedom, freedom come an’ it won’t be long.”

As Baylor Professor Robert F. Darden describes the incident in a recent article for The Dallas Morning News, Poitier and Belafonte did not object to sleeping in a single bed at a small house in Greenwood, with armed guards watching over them as Klan members lurked nearby that night. The two stars even jokingly bickered over who got to sleep furthest from the window in case the Klan tried to shoot them; Poitier insisted that he get the side away from the window. The two men left Mississippi the following day, but remained active in the Civil Rights Movement. Poitier, for example, was a public supporter of Dr. King’s Poor People’s Campaign.

Belafonte has told the story of their trip to Mississippi several times over the years. Though very vocal about civil rights and Black uplift, Poitier rarely spoke of the Mississippi trip publicly, although both men discussed it in interviews for the 2011 documentary Sing Your Song.

In Susanne Rostock's 2011 documentary Sing Your Song, Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier describe their trip to Mississippi in 1964 to assist the drive for voter registration. pic.twitter.com/puM05sv9HE

— Dr Karen McNally (@hollywoodfilmtv) January 7, 2022

Poitier's long life and career have left no shortage of memories, and his 1964 trip to Mississippi has rightly resurfaced as a testament to his legacy. His willingness to risk his life to serve the cause of Black freedom and to help a friend was emblematic of the life he lived. That he did this so soon after making history and receiving the highest honor in acting only enhances his legacy. As we honor the ways he impacted America in general and Black people in particular, the actor's mission to Mississippi endures as a real-life adventure as compelling as any movie.