Harassment and hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have gone up significantly over the past year. Largely fueled by the racist rhetoric used by former President Donald Trump to deflect attention away from his administration’s failure to manage the COVID-19 pandemic, hostility against people of Asian descent has been displayed in a large string of public incidents and even violent attacks. Last week’s killings of eight mostly Asian workers and patrons in three Atlanta-area massage parlors is the most horrific of such hostility toward the Asian American community in recent years.

Meanwhile, hostility towards Black people — from racism to discrimination to police brutality — remains a huge problem within the United States. While Black and Asian Americans have many reasons to find common cause in mutual struggles against racism and xenophobia, much of the narrative of late has focused on divisions or tensions between the communities.

Such narrative is not only divisive but also obscures the long history of Black and Asian cooperation in the United States. Here are five examples of such solidarity.

World War II And Black-Japanese Solidarity

After the United States went to war with Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor, over 100,000 Japanese Americans, mostly in California and other parts of the American West, were interned for the remainder of the war. As historian Natasha Varner notes, many Black Americans who had moved West during the Great Migration moved into neighborhoods such as “Little Tokyo” in Los Angeles.

Despite some tensions between Black and Japanese residents of these areas, solidarity developed between the communities. Black activists publicly denounced internment, while the Black friends and neighbors of those interned visited and brought supplies to their incarcerated Japanese American neighbors. Solidarity remained after the war. Numerous Japanese American activists in the 1940s and beyond opposed segregation and supported equal rights for Black Americans. For example, Ina Sugihara became a founding member of the Congress of Racial Equality, one of the key organizations of the Civil Rights Movement.

Asian Support For Black liberation

The American Civil Rights and Black Freedom Movements coincided with the post-WWII process of decolonization, as people across Africa, Asia and around the world fought for and eventually gained independence from Britain, France and other colonial powers. Many leaders in Africa and Asia found a common cause in supporting one another’s struggles. The 1955 African-Asian Conference, held in Bandung, Indonesia, led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement. This coalition of countries from both regions – later expanded to include areas such as Latin America as well – sought to cooperate as a third force attached to neither the Western nor Communist blocs. The follow-up Afro-Asian Peoples' Solidarity Conference of 1957 and subsequent establishment of the Afro-Asian People's Solidarity Organization to promote cooperation and mutual defense between these two regions against exploitation.

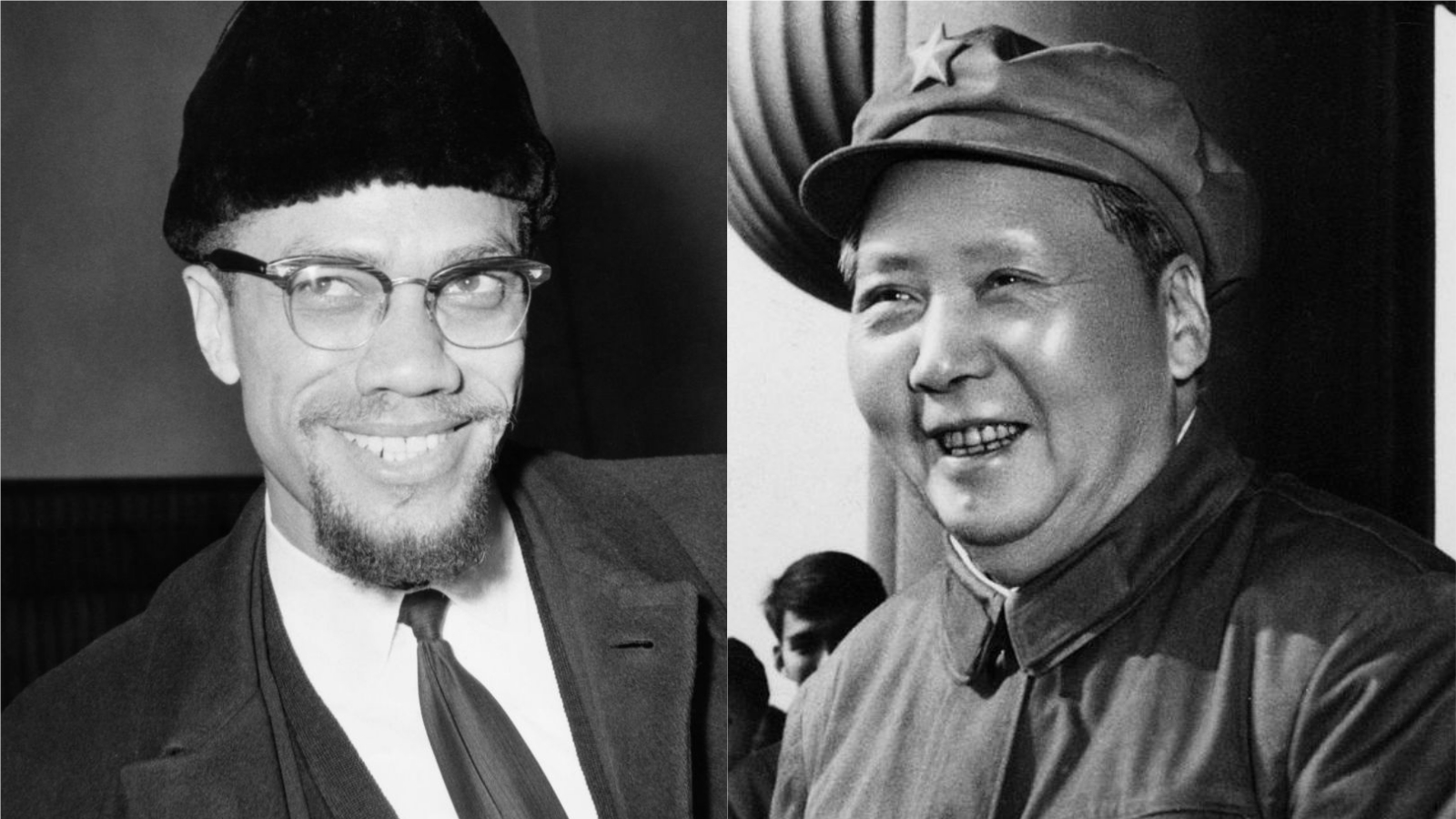

Chinese support for Black liberation included public rhetoric espousing solidarity with various freedom fighters and struggles. In 1963, Chairman Mao Zedong delivered a major speech “call[ing] on the workers, peasants, revolutionary intellectuals, enlightened elements of the bourgeoisie and other enlightened persons of all colors in the world, whether white, Black, yellow or brown, to unite to oppose the racial discrimination practiced by U.S. imperialism and support the American Negroes in their struggle against racial discrimination.”

Although the People’s Republic of China was not a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, communist China often made common cause with people around the world fighting imperialism and racism. Black American leaders like Malcolm X

spoke favorably of Zedong and presented China as a model for colonized Black people to follow to gain liberation and recognition.

A number of Black leaders visited Zedong and other top Chinese officials at various points. Those traveling to China included famed scholar W.E.B. Du Bois; Black Panther Party activists Huey Newton, Elaine Brown and Robert Bay; and Black American exiles Robert F. Williams and Vicki Garvin.

The Civil Rights Movement And Immigration Reform

Prior to the 1960s, Asian people faced some of the harshest immigration restrictions of any people in the world. After immigrants from China and Japan began coming to the U.S. in significant numbers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they faced hostility due to their cultural differences and because of their competition with white workers for jobs. In response, the U.S. Congress passed a series of laws that severely restricted the ability of people from Asia to migrate to the U.S. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Scott Act of 1888, and the Geary Act of 1892 restricted Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. and required strict registration and verification procedures for those already living in the country. Finally, the Immigration Act of 1917 banned most immigration from a “Barred Zone” that included most of Asia and the Middle East, and the Immigration Act of 1924 denied entry to most Asian people – primarily Japanese – who had not been covered by the 1917 law. Subsequent laws set restrictive racial and ethnic quotas limiting the number of people who could immigrate to the U.S. from various countries.

Sentiments about preserving the whiteness of America began to change with the Civil Rights Movement, making the idea of white supremacy, whether enforced through segregation or exclusionary immigration laws, unacceptable. Presidents John F. Kennedy and then Lyndon B. Johnson made both civil rights legislation and immigration reform key policy goals. Finally, less than two months after Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he signed into law the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which eliminated race-based immigration quotas and racial or nationality-based discrimination in immigration policy. Thus, the Civil Rights Movement also opened the country’s doors to Asian immigrants who had been excluded for decades from entering the country.

The Creation Of "Asian Americans" And Ethnic Studies

It’s relatively rare that we can pinpoint the exact time and place in which a new identity is created, but in the case of Asian Americans, we know who coined the term where and why. In 1968, graduate students and future husband and wife team Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee founded the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) at the University of California, Berkeley. Ichioka, who became a professor at UCLA, purposely created the term “Asian American” as a way of uniting people of various national origins under an umbrella term and common identity to increase their political and social power.

In doing so, Ichioka, Gee and other AAPA activists cooperated with and were explicitly inspired by the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. Richard Aoki, one of the founding members of the AAPA, was also the only Asian American to achieve a leadership position in the Black Panther Party. Although later information revealed Aoki to be working for the FBI, the solidarity between the Black Power and Asian American rights movements was real and influential during the 1960s and '70s. For example, the AAPA branches at UC Berkeley and San Francisco State College participated in the “Free Huey” movement aimed at defending Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton against murder charges.

One of the common causes that united Asian American and Black student activists was the desire for Ethnic Studies programs. The joint activism of organizations representing these groups, alongside their white and Latino allies, led SF State College to create the first Black Studies program in the country in 1968. The first Asian Studies programs began the following year at SF State, Berkeley and UCLA.

Asian American Support For Affirmative Action

Recent legal actions have appeared to represent Asian American opposition to affirmative action, based on the idea that policies that promote Black and Latinx admission into colleges and universities penalize Asian American applicants. The recent case Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard is a high-profile case in this narrative, and the Trump justice department supported a similar case against Yale University.

The popular narrative, however, hides several important points. For one, although Students for Fair Admissions claims to represent Asian American students, the organization was founded and bankrolled by a white conservative activist, Edward Blum, who has conducted a long campaign against policies that use racial considerations to counteract racism – for instance, Blum was instrumental in the Supreme Court decision that weakened the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Many critics argue that Blum and other white conservatives are exploiting Asian American students and attempting to pit them against other minority populations.

Despite the framing that has been put around these issues, 70% of Asian Americans support affirmative action, according to recent survey data. In fact, this support appears to have actually increased during the time that the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit was being litigated. Additionally, many Asian American students likely benefit directly from affirmative action, including many students whose families initially came to the U.S. as refugees and who often experience poverty and other hardships. Affirmative action might therefore help to lessen the widening income gap that exists within the Asian American community.

As many Asian Americans face the same socioeconomic and institutional barriers to higher education that impede Black and Latinx students, the fight to protect affirmative action represents yet another instance where these populations have common causes to support one another. Now, with these communities being potentially pitted against one another, all while violence rises against Asian Americans and remains targeted against Black Americans, solidarity and mutual support are as important as ever.