The Caribbean is a victim of undivulged history. During colonialism, black Africans who were forced into slavery in the Americas experienced a rupture in their historical trajectory. They had no choice but to subject themselves to Eurocentric histories, or what Edouard Glissant calls “History with a capital H”.

In the 1950s, the British government’s scheme, which was later named “Operation Legacy”, required representatives in decolonizing regions to hide documents that would either incriminate British officers, embarrass the monarchy, reveal racist motives…or all the above. Not only were the African slaves’ histories obstructed, but details of colonial occurrences were also compromised.

Still, Africans’ spirits, cultures, and languages remained enigmatic to the colonizers. The use of language was particularly pivotal to much of the cultural and historical productions in Jamaica. On one hand, British planters forced slaves to speak English and enroll in European-informed education systems. On the other hand, they transformed the language into Patois: a language that at first listen sounded like English, but was a linguistic diversion influenced by imported vernaculars and submerged idioms of the slaves.

Eurocentrism and white supremacist tactics afforded colonial and imperial authorities the power to construct history. However, by examining three types of cultural productions—literature, oral storytelling, and music—one can see the ways in which Jamaicans used both English and Patois to communicate their identity and experiences, and thus challenge Western historical records in the 20th century.

During colonialism, Caribbean narratives were told through the lens of the white minority, and following emancipation, imitative literature reached its peak as Caribbean people denied their African heritage and align themselves with British culture.

The mid-1900s and beyond saw a shift in this mentality. Western-educated black Caribbean writers used their knowledge to produce poems, novels, and academic texts that responded to, challenged, or appropriated Western literary frameworks. For example, in his 1955 autobiographical novel, In the Castle of my Skin, George Lamming discusses themes of race, power, social hierarchy, and migration, while grappling with the legacy of colonialism and slavery in the 20th century Barbadian village. As well, in 1969, Aimé Césaire wrote Une Tempête, a postcolonial response to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which addresses race, power, and decolonization.

Postcolonial scholars have debated the revolutionary power of English among non-Europeans for years. However, using the master’s tools by speaking English and getting educated abroad proved a useful strategy because literature was and still is vital to shaping people’s imaginaries. By adopting dominant practices, Caribbean writers could critique Eurocentric historical accounts, while also presenting (potentially oppositional) intellectual ideas and thoughts that would be taken seriously by the hegemonic group.

Oral storytelling has long been used in lieu of historical data, or when narratives have silenced the colonized and oppressed. Like Patois, oral storytelling is characterized by its blasts of sound and total expression, and its intimate relationship and involvement with society provide a basis for which storytellers can comment. This approach connects the community with African oral tradition and provides authenticity to the story’s original meaning and expression.

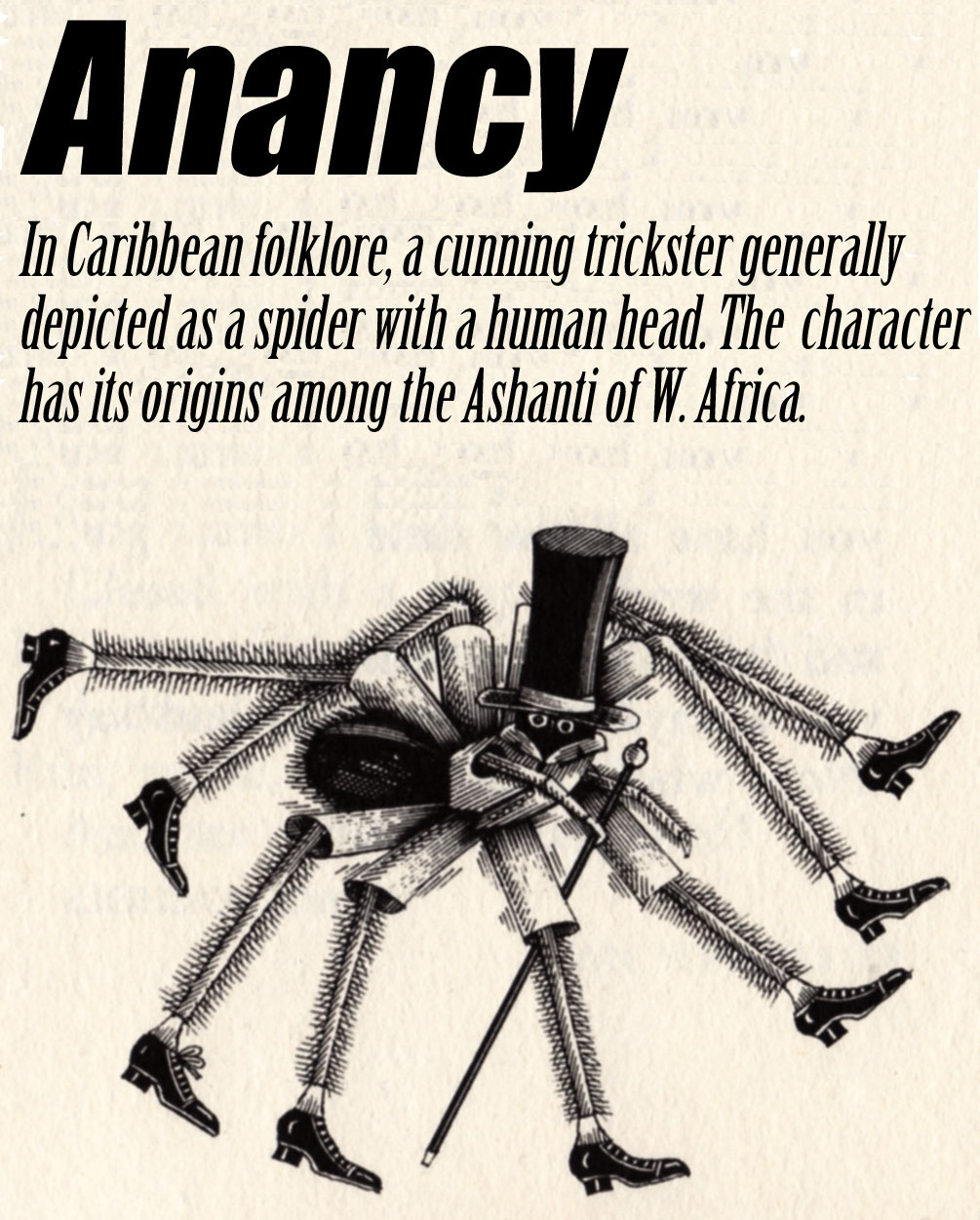

Anansi/Anancy stories originated from the Ashanti tribe in West Africa and are an example of oral stories that were transported to the Caribbean during the slave trade. In this new context, stories of the human-like spider character were told in Patois and stood for resistance, blackness, and power. In the stories, his cunning is often directed towards predators that are perceived as more powerful or well-respected (e.g. tigers, snakes, and lions), and he uses speech and intelligence to outsmart them.

Anancy demonstrated the power of subversion and even inspired strategies of resistance. These oral and now published tales revealed the ways in which seemingly inferior groups can use wit (as opposed to physical force) to defeat their oppressors. Anancy gave hope to those who also faced tyranny and inequality, while also challenging colonial texts that were ignorant of Afro-Caribbean folk culture.

Adorno once said music is representative of a nation and its principles. This is evidenced in Jamaica by the advent and popularity of reggae music in the late 1960s. Inspired by ska, certain sounds symbolized the rejection of white-man culture, while others symbolized ghetto life and reggae’s working-class roots. Rastafarians used reggae to protest the unjust social conditions faced by Jamaicans and other people of color. For example, Rastafarian musician, Mutabaruka’s 1986 song, “The Eyes of Liberty”, calls out American imperialism, US bombings, and the oppression of indigenous and black groups. Musicians such as Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Junior Reid, and Carl Dawkins also discussed issues concerning poverty, injustice, racism, and bondage.

Reggae also entered the political realm in the early 1970s, when the Jamaican People’s National Party (PNP) led by Michael Norman Manley celebrated the taboo Rastafarian culture and used the genre to demonstrate shared concerns. The familiarity and ease with which he appropriated Rastafari culture and music appealed to progressives and underprivileged communities and assisted in his victory against the conservative Jamaican Labour Party (JLP) in 1972. Although Manley’s strategy was not entirely sincere, reggae was evidently more than a genre of music that commented on problems; it was also a means through which people could communicate to powerful figures the concerns of disadvantaged communities, and actually have these issues addressed.

Jamaican culture has been hybridized from the beginning, and as such, its dominant African and European influences contributed to the people’s strategies of resistance and cultural visibility. While some Caribbean writers wrote scholarly and Western-inspired texts to contest Eurocentric texts and histories, others used Patois to connect with and provide a voice for less privileged Jamaicans.

Operation Legacy and its proprietors did their damage, but the potpourri of literature, storytelling, and music has cemented some poignant events and shaped the Caribbean people’s history, culture, and collective identity. Indeed, although they will never gain the full story, Caribbean citizens have made sense of their histories through various strategies and modes of cultural production. And in the process, they have reclaimed the power to tell their own narratives.