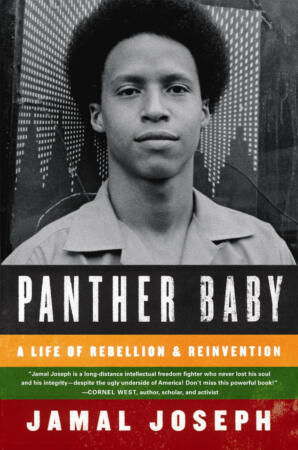

Jamal Joseph’s latest feature film “Chapter &Verse” is currently touring the USA after a film festival run, and opening in New York City and LA last month. Check your local listings. He also appeared in director Stanley Nelson’s documentary “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution” which is currently available on various home video platforms.

“We were taught to have an undying love for the people, we were taught to serve the people mind, body, and spirit.” — Interview with former Black Panther Jamal Joseph

In 1968, 15-year-old Eddie Joseph was on the cusp of graduating high school. But, like many of his young contemporaries, his eye was caught by the burgeoning Black Panther Party. This group, which advocated for armed self-defense against police harassment, was founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, and was beginning to gain serious national traction.

Operating from the basis of an ambitious and attractive 10-point program (point 1: “We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our black community”), the Panthers offered young, disenfranchised African-Americans communal purpose and a platform to battle against social inequality. They would later make community social programs a key part of their offering. However the provocative group were soon subjected to intense government scrutiny, most notably in the form of the COINTELPRO program conceived by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. They also became riddled with informers and undercover cops.

In 1969, Joseph was charged with conspiracy as one of the “Panther 21” in one of the decade’s most infamous criminal cases. The eight-month trial was the longest and most expensive in New York State history, but the Panther members were acquitted of all charges on May 12, 1971—a staggering total of 156.

Eddie changed his name to Jamal and became the youngest leader and spokesperson of the Panthers’ New York chapter. He joined the “revolutionary underground,” but shortly found himself back in prison, this time for his role in the murder of Panther Sam Napier in April 1971. He was later sentenced to 12½ years in Leavenworth prison, Kansas, for another crime: the Brink’s armed robbery of 1981.

He served 5½ years, during which time he earned two degrees and began writing and acting in the prison theater company — skills he’d later put to good use when founding IMPACT Rep Theater in 1997. This led to his hiring as an adjunct professor at Columbia’s School of the Arts. He’s since written books (a biography of Tupac, an autobiography); worked in the theater as a director and playwright; and he’s even been nominated for an Oscar, in 2008, for his contribution to the song “Raise It Up” from the film August Rush.

Joseph is one of the most compelling figures in Stanley Nelson’s absorbing documentary, “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution,” which examines in detail the spectacular rise and fall of the party. I spoke to him about his early experiences with the Panthers, how their plight is relevant today, and his remarkable journey.

You were only 15 when you joined the Black Panther party. What motivated you to do so?

Jamal Joseph: When you’re young, you’re looking for your own identity. That’s why a lot of kids join gangs, right? It’s someplace where your anger can be focused. There’s a camaraderie and love that isn’t found in schools or even, sometimes, in your home. The Panthers came along, throwing the finger at the government, with cool imagery, leather coats and berets. They appealed to young people’s hormones, and resonated with a group of oppressed people that were saying, “I want to be free.”

As we used to say in Harlem, and in Kansas: a black grandmother could call for a cop and say, “There’s a man on my fire escape trying to kick in my window and get into my apartment,” and the police would come 30 minutes later, if at all. In a white store, they could say, “There’s a black man across the street looking like he’s thinking about robbing my store,” and they’d arrive before he could even hang up the phone.

You put all that together, you go into the Panther office, and you’re immediately given some clarity about your life, about what’s wrong, and about what you can do about it, like right now.

It’s too obvious and reductive to call the film “timely”, but there’s no doubt that its subject matter — particularly the aspect of young African-Americans mobilizing against the reality of police brutality — resonates with the social and cultural climate we’re in now. I’m thinking of #blacklivesmatter protests in Ferguson and Baltimore, and the seemingly incessant stream of incidents: Eric Harris, John Crawford, Sandra Bland…

We do literally see it [police brutality] more now, because everyone has a video camera in their pocket, and we are able to document it. People in poor communities, and in black and brown communities, always knew this was true, but now the wider world is seeing that it’s undeniable.

As someone who’s seen anti-black police brutality first hand in America since the 50s and 60s, can you talk about its perennial nature?

The reason why the problem of police brutality hasn’t gone away, and the reason why it’s getting worse, is because the underlying reason for it is connected to the underlying reasons for income inequality, for inadequate healthcare and poor education in schools and the growth in [number of] prisons. It is that the police and military are not there to protect the people, and certainly not to protect poor black and brown people. They are there to protect the state… They are there to protect the wealthy and those who intend to make the state wealthy.

The disturbing argument made by writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates (“Between The World and Me”) and Michelle Alexander (“The New Jim Crow”), is that this situation reflects precisely how the state is supposed to function. That it’s not an aberration…

That’s exactly what I’m saying. We’ve got to talk about the attitude of people vs. property. What’s more important? If we don’t talk about that, and if we don’t organize along class lines, not just race lines… if we don’t organize around the redistribution of power and income inequality, these things will continue to happen. So you can’t just wag your finger and say that cops are mean. Why are they militarized? Why do they occupy the community like an army? What are they responding to, if not to the lives of the people in that community?

When uprisings happen, people say, well, “Why would you burn down stores in your own community?” It’s because the people feel no attachment or value to that. In a subconscious way — or sometimes in a very conscious way, [stores] represent the property of the state, not property of the people, and so folks are lashing out. The people don’t benefit from them being there, especially when stores are charging high prices, and they aren’t employing enough folks in the community. Also, you go there to shop and you’re followed like you’re going to steal something. The store becomes a symbol of the state and provokes resentment.

As the film highlights, the Panthers looked at globalizing the struggle against oppression — they opened communication with North Korea, and lots of African countries. Was that central to your thinking, personally?

Yes. The Panthers realized that the white folks, brown folks, yellow folks, red folks can be with you in this struggle. When you talk about that, you really are talking about the majority organizing and fighting the minority. That’s the strategy that can win. It was “all power to all the people” that got us wiped out, like Dr. King and Malcolm X – they were both assassinated at the point that they were both talking about capitalism, class struggle, and all people coming together. The government went, “Ok, you’ve got to go. Because now, now you’ve really hit Achilles heel.”

Thanks to the Panthers being founded in Oakland, they’re often discussed in the media within a Californian context. Can you talk about the Panthers in New York?

The gun laws in New York were different than they were in California; there was no question of “open carry”. So we organized around housing, food, education, schools, and working with the community around those issues. They were very long, dangerous days, because we were confronting cops, drug dealers, and slum lords, many of whom had mafia connections. There was danger with every step.

A substantial section of the film is dedicated to the saga of the Panther 21. Can you tell me about it?

Some undercover cops, who were part of an elite police unite known as the BOSS unit (Bureau of Special Services), infiltrated the Panthers, and identified leaders: the number they came up with was 21. I was the youngest, but I was the head of the high school chapters. They took some of the rhetoric that happened at our meetings, some of the physical fitness and weapons practice, and fashioned it into a narrative — a lie — that we were planning acts of criminal warfare in New York City.

I found myself being arrested at 3am on April 2nd, 1969, taken out in chains and handcuffs from my grandmother’s house and then getting to the police precinct. Initially we laughed at it. Panthers were getting arrested almost every day someplace, for selling Panther newspapers, for weapons possession, whatever. And then we found out about this incredible conspiracy case. It turned out that one of the undercover cops involved had been my mentor. His name was Ralph White. He’d actually taught me how to communicate to the breakfast program kids, and hand to hand combat. When my grandmother found some Panther literature in my bedroom, she freaked out and said I couldn’t go back. Ralph came to my grandmother’s house and convinced her to let me to stay because he would look out for me. So that was the nature of the case.

Can you quantify the impact of what happened?

Families were broken apart, breadwinners couldn’t support their families, and it helped to foster an attitude of fear and terror around the Black Panther Party: You had people begin to actually believe that this is what we were going to do.

However the main thing was that it became an incredible rallying point for the New York community who personally knew the work of the Panthers. These were people who’d seen the Panthers feeding their kids, taking care of the elderly, fixing broken down apartments, getting people medical care, day in and day out. So they couldn’t reconcile what they saw in the newspapers and on the news with who they knew. They began to come to court, they could see what was going on and compare it to what was happening to Panthers all around the country. The authorities probably thought was going to be an open and shut case, but it became a rallying cry for people to support the civil liberties of people standing up to the government.

The 21 was only one of many instances of Panthers being deliberately suppressed by the state. [Co-founders] Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were both imprisoned at points. [21-year-old Illinois chapter chairman] Fred Hampton was murdered by police. Stanley’s film ends with a depiction of the Panthers going out with a whimper, defeated by state surveillance and internal strife. How do you interpret the group’s decline?

The Panthers could not survive battles from within and from without. We were dedicated, we were brave, we were smart, but we weren’t perfect—there were personality conflicts and human flaws. And the FBI’s program preyed upon both individual and organizational weaknesses. And they also did a lot more than prey on weaknesses: they framed people, they murdered people, they created extremely negative atmospheres of mistrust.

And some years later, you went back to prison.

It never really felt like I escaped. The main thing about my time in prison was realizing that revolution might not take the form that I thought [using force], but there still needs to be revolutionary consciousness and change, and that’s why I threw myself into education and the arts and thinking that I could come out and work with young people. I realized how much I’d gotten from older people that took the time to work with me when I was that age. That became the focus.

I’m the same person inside as that young man who walked into the Panther office looking for a place to belong and looking for a way to change things in my own life and around me. I’m still looking for those ways. I still believe there’s no better way to do it than through the power of the people, and there’s no better way to animate the power of the people than by loving the people.

And art, too?

Art speaks directly to our heart and to our spirit. It’s a great way for me to organize people.

You’ve served as the Chair of Columbia’s Graduate program for film. What’s your favorite film?

I prefer films that can motivate us to make changes in our own lives. Hunger by Steve McQueen is film at its best and social activism at its best. It humanizes that struggle. It really shows you who Bobby Sands was as a person, what the struggle was about, and the choice that he made: to make the ultimate sacrifice because this is what he had to do to make a point and to lead the people struggle, the people’s revolution in Ireland.

Do you keep in touch with other Panthers? Is there still a sense of community?

There’ll be one or two events a year that folks will come out for, and you’ll catch up with everyone and stay in touch with those. Panthers will often reach out to me because they want me to bring all the kids from my youth program to perform at their events. The kids in my program have a lot of what they call Panther Aunts & Uncles.

How do you look back on Panthers now?

The youth side of it scared the establishment because we weren’t just mad kids. We had a real analysis of the problem. In today’s world, we’ve got armies out there, in the form of gangs; we have them in the thousands. They outnumber the Panthers, even at the height of our movement. And they’re not being attacked in the same way. In fact the authorities kind of let them exist, and let them shoot each other and build more prisons. They solve the problem that way. It’s a legal lynching.

And if you ask any Panther what was their main motivation for being in the organization, they won’t quote the ten-point program, or talk about socialism or police brutality. They would say we were taught to have an undying love for the people, we were taught to serve the people mind, body, and spirit. I guarantee you that any Panther will answer the question that way. I guarantee this. I’ve never been wrong about this.

Ashley Clark is author of “Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee’s Bamboozled.” Follow him on Twitter.