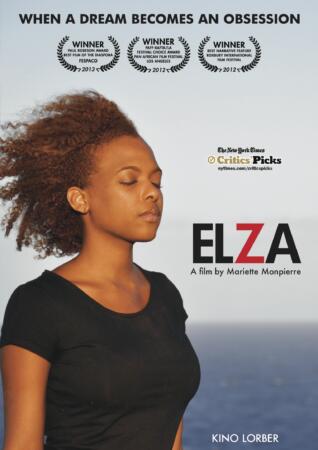

Screening at the Pan African Film Festival this Saturday, February 11 at 7pm, and again on Monday February 13 at 6:10pm is “ELZA” (“Le Bonheur d’Elza” or “Elza’s Happiness”), the first narrative film by Mariette Montpierre, and the first feature film directing effort ever by a Guadeloupean, which was inspired by Montpierre’s personal accounts of searching for her biological father back in her native West Indies.

The story follows Elza, living in Paris with her mother Bernadette (played by director Montpierre), celebrating completing her Master’s degree. But the successful young woman (played by the lovely Stana Roumillac), has never come to terms with her sense of identity. Her biological father, whom she barely remembers, is back in her hometown of Guadeloupe tending to another family. He abandoned them when Elza was a young child. Her enraged mother threatens Elza not to leave, but the willful free-spirit embarks on her journey.

A charming and vivacious Elza basks in Guadeloupe’s beaches and scenery. Hopeful and optimistic, she travels on her motorcycle through the succulent landscapes of the island; a Black woman wearing her natural hair, sans helmet, riding her motorcycle, exuding subtle sensuality, passionate about life, free and unburdened.

But Perhaps Elza is too optimistic. She tracks her father down; Mr. Desiré (Vincent Byrd Le Sage), a man of mixed race. He’s powerful, wealthy and a well-known figure in her hometown. She follows him as he meets up with a Black mistress, and later to his home, which he shares with his fair-skinned wife, and granddaughter Caroline (an adorable Eva Constant).

Unbeknownst to the man of the house, who doesn’t know who she is, Elza infiltrates her birth father’s home and becomes the caretaker of his granddaughter (her niece). She earns the trust of Mr. Desiré and his wife, but most of all, of their non-responsive granddaughter, who has formed a strong bond with Elza.

Even though things are going fairly well, Elza’s goal of reacquainting with her father is nowhere near being accomplished. He has two other daughters from his current marriage. The youngest is in a mental facility. The father of her child, Jean-Luc (Teddy Doloir) was rejected by her parents; he was deemed too “dark/black” to join the family. And Mr. Desiré’s oldest daughter, an ill-tempered woman, is in a passion-less marriage with a lascivious man who begins to lust after Elza.

She also realizes the family’s deep-seated prejudice against darker-skinned black people. The young granddaughter is not allowed to see her father Jean-Luc. In one scene, Jean-Luc shows up at their doorstep to deliver presents for his daughter. Elza watches as Mrs. Desiré yells at him not to come back. She then gives the wrapped presents to Elza to put in the garbage.

Yet, Elza’s memories of the seemingly cold-hearted Mr. Desire embracing her as a child still haunt her. She sees the prejudice and feels displaced, but she also knows that the daughters he raised with his current wife aren’t happy and don’t share a close bond with their father either. She still yearns for his love and attention. She feels she deserves it. She must somehow win him over. And, although deep inside one may root for her, the most sensible alternative is to forget everything about this man and his dysfunctional family, and walk away with pride and dignity in tact.

Yet Elza is stubborn; her father’s acceptance becomes her obsession. As the narrative unfolds and Mr. Desire finds out the truth about Elza – a truth he had been suspecting – he’s in denial and can’t face her. “Please look at me,” Eliza cries in the climactic scene, to which Mr. Desiré replies with his back to her, “With your kinky hair, you can’t be my daughter.”

Writer/director Montpierre develops a narrative that shows the complexities of Caribbean racial prejudices, after centuries of miscegenation due to French-European colonialism in Guadeloupe. Racism takes a form similar to what’s considered “Colorism” in the states, although more severe. There’s a hierarchy based on skin tone and hair texture. Unfortunately for many “higher-class” Caribbean people, the colonially racist and paternalistic mentality persists; for example, black women seen as inferior – either mistresses/sexual objects or nannies. It’s a hypocritical, absurd notion, especially considering at Mr. Desiré’s and his other daughters’ own dark olive skin tones, his love-affair with his black mistress, and his own obviously mixed granddaughter.

In real life, filmmaker Montpierre was optimistic about meeting her biological father, and she wanted to end her film with a more positive outcome than what actually happened in her own true story. Her father died a year after she met him, and even while she got to know him, theirs wasn’t the close relationship she had hoped for. Yet, in real life, her father’s family embraced her; they supported her and the film.

With “Elza,” Montpierre hoped to reach out to fatherless women in the title character’s situation who are looking to find closure. In the process, they may also find forgiveness, acceptance and a new family.

The only criticism I, and certainly others, would have is that the romanticized ending may come across as too simplistic. It’s hard to reconcile the prejudices against Elza, and her father’s unethical ways. Yet you don’t really mind it here due to the beautiful, affecting performances, especially by the arresting Roumillac as Elza, and Le Sage as her father; the latter’s transformation is superb as he sheds his layers and evokes genuine sentimentality.

The cast, consisting of mostly non-professional actors, deliver believable performances. There’s an air of feminine energy throughout the film, bolstered by the picturesque scenery, Elza’s allure due to her tenacity, strength and vulnerability, the film’s score – a mixture of sensual ballads and vibrant beats – and the film’s rich emotional energy.

If you’re in Los Angeles, see it at the PAFF this Saturday or next week Monday when it screens a second time. Tickets here.

Watch a trailer for “Elza” below: