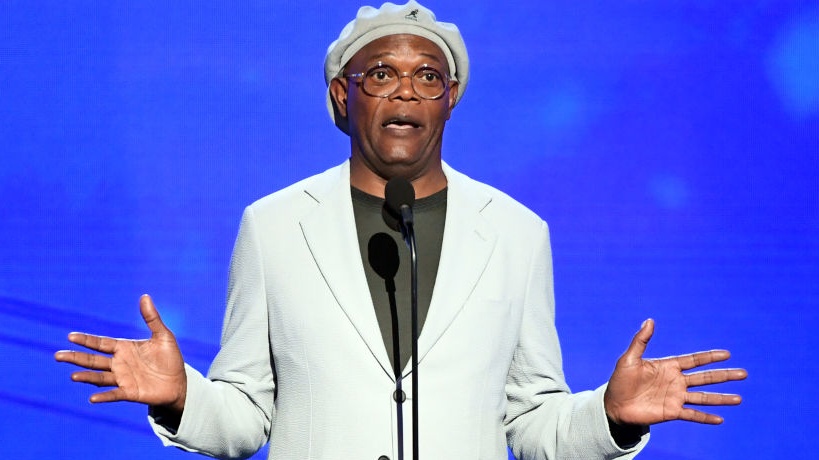

Actor Samuel L. Jackson was enraged after the killing of Martin Luther King Jr. The April 4, 1968 assassination of the civil rights leader lit a fire under the then-young Morehouse College student, and he began to call a lot of things into question, including his school's administration and the ways for which they governed the men's HBCU.

One of those administrators was Martin Luther King Sr., father of the slain movement leader. But before King Sr. would face Jackson's wrath, the grieving father would see the student serve as an usher at his son's funeral services.

In a 2018 interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Jackson said he learned of the younger King's death while preparing to go to a campus movie night. Following a quick trip to protest in Memphis, Tennessee, where King Jr. was slain, Jackson answered the call for volunteers to lead a mourning community around campus.

"We flew back that night and went to Sisters Chapel at Spelman College, where Dr. King was lying in state," Jackson told The Hollywood Reporter. "The next day was the funeral. They needed volunteers to help people find their way around campus, and I became an usher. I remember Mahalia Jackson singing. I'd been listening to her all my life, so it was great to hear her sing "Precious Lord, Take My Hand" live. I remember seeing people like Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier. People that I thought I'd never see, let alone have a relationship with later on in life. The funeral was pretty much a blur."

In a 2005 interview with Parade, Jackson credited the historical event as the thing that amplified his desire to create social change in a different way.

“I was angry about the assassination, but I wasn’t shocked by it. I knew that change was going to take something different – not sit-ins, not peaceful coexistence," Jackson said.

And then came his own radical activism.

'I came to a realization that we [Morehouse students] were being groomed to be something that I didn't necessarily want to be," Jackson said. "The Morehouse College administration was rooted in some old-school things that the majority of us students didn't believe. 'You would be a great doctor, a great lawyer, maybe a great scientist.' I was skeptical of that. I didn't want to be just another negro in the, you know, advancement of America card. We had no connection to the people that we lived around. I was skeptical of that. We didn't even have a Black studies class. There was no student involvement on the board. Those were the things we had to change."

To create the desired change, in 1969, Jackson and fellow protesters petitioned the Morehouse board for a meeting. But when the board declined, the angry students used chains that were meant to keep them from walking on the grass to lock themselves in a room with the board members.

"Our understanding was that, once we locked them in, we were in violation of a whole bunch of laws. Dr. King's father, who was on the board, had some chest pains," Jackson said. "We didn't want to unlock the door, so we just put him on a ladder, put him out the window, and sent him down. The whole thing lasted a day and a half."

During the negotiations, Jackson recalled that the administrators agreed not to expel them, however, the participating students were indeed expelled anyway. Jackson became even more radicalized.

"I was anti-war because my cousin had been killed, so I had been radicalized in that way, Jackson said. "I got caught up and actually started to think that there was going to be an armed rebellion in America. It wasn't just going to be a racial war. It was going to be more than that. It's basically what it is now. Young against the old. The establishment against the anti-establishment. We were buying guns, which kind of put me on the radar of the powers that be. We were fully expecting a revolution to happen. That summer of '69, somebody from the FBI came to my mom's house in Tennessee and told her she needed to get me out of Atlanta before I got killed."

His mother sent him to live with his aunt in Los Angeles where he worked for two years in social services. He then reapplied to Morehouse and returned to study drama in January 1971, finishing his degree the following year.

“I decided that theater would now be my politics. It could engage people and affect the way they think. It might even change some minds," he told Parade.

Jackson later teamed up with fellow Morehouse graduate, Spike Lee, to work on some of his early films, including School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), Mo' Better Blues (1990) and Jungle Fever (1991). His career skyrocketed in 1994 with his role in the film Pulp Fiction, for which he was nominated for the Academy Award in the best supporting actor category. He has since garnered an estimated $250 million net worth with more than 150 film credits to his name, grossing an average of $89.9 million per film.