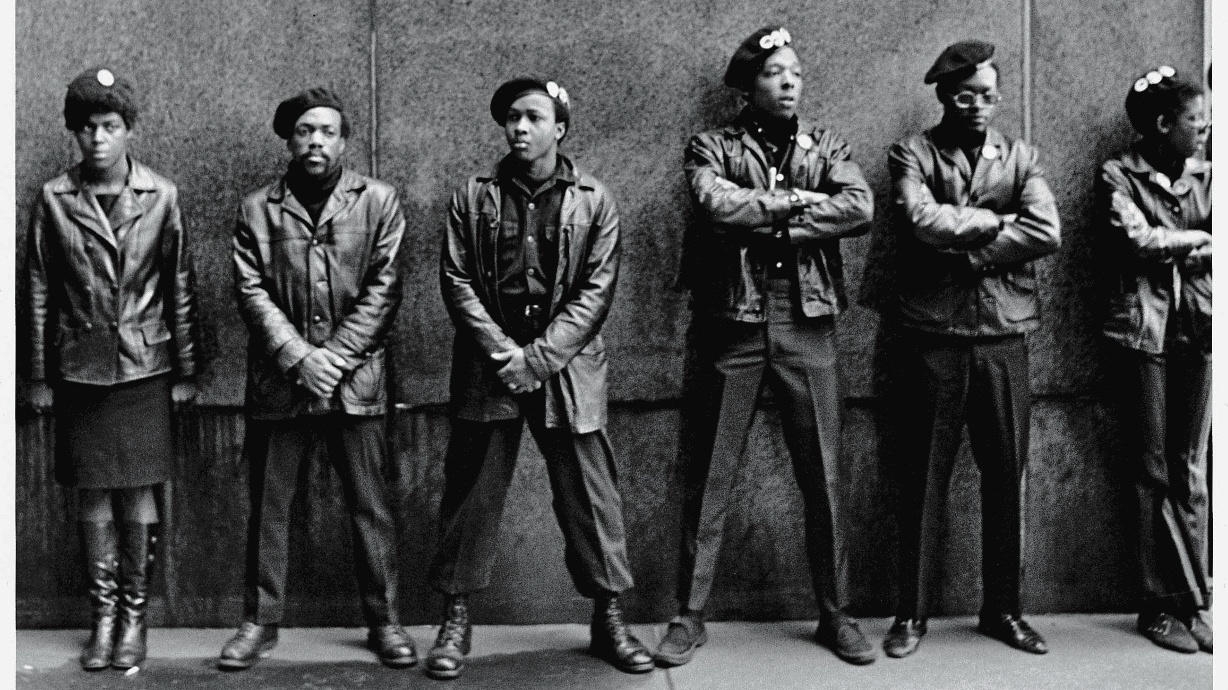

On April 2, 1969, 19 men and two women associated with the newly-formed New York branch of the Black Panther Party were arrested in a series of early-morning raids. The “New York 21” were charged with conspiring to commit violent attacks against a number of targets across New York City.

The arrests happened during a time of heightened racial tensions and hostility, sometimes violent, between groups like the Panthers and law enforcement. In 1969, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover declared that “the Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to internal security of the country” and promised to destroy the organization.

This was not an idle threat. Federal forces including the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program or COINTELPRO devoted extensive time and resources towards undermining, discrediting and even assassinating Black groups like the Panthers. One historian documents that two dozen Panthers were killed by police and hundreds more arrested in 1969 alone. One of the most infamous instances of this anti-Panther campaign, for instance, was the police assassination of Fred Hampton, the leader of the BPP’s Illinois branch, which occurred eight months after the New York raid.

The arrest of the New York 21, also known as the “Panther 21,” was intended to strike a major blow against the Panthers and against Black militancy more generally. These efforts, however, largely backfired. The case gained national attention. Famed composer Leonard Bernstein hosted a ritzy Manhattan fundraiser for the 21, an event that then inspired a New York magazine cover story by Tom Wolfe, who dismissed the idea of rich New Yorkers supporting Black militants as “radical chic.”

Partially inspired by members of the Panther 21 who were imprisoned there, inmates at the Branch Queens House of Detention rebelled against prison guards and administrators in 1970. This move forced New York authorities to review the detention of several Panthers who were granted bail. The trial helped to reveal the secretive operations of New York’s Bureau of Special Services, or BOSS, a special unit that had infiltrated groups including the Panthers and Malcolm X’s inner circle ahead of the latter’s assassination.

The main trial, featuring 13 of the 21 defendants, was largely built on the testimony of three people who had been planted to make their way into the Panthers group as part of the larger campaign by COINTELPRO and BOSS against the organization. The three undercover agents testified that they had witnessed members of the Panthers train and plot based on an extensive plan to bomb targets in New York City, including police stations and even the Bronx Botanical Gardens.

Despite this testimony, the prosecution presented little evidence to support the accusations against the Panthers. After an eight month trial – one of the longest in New York history – the defendants were declared not guilty on all charges. On May 12, 1971, after less than a day of deliberation, the jury returned to court to read a total of 156 “not guilty” verdicts for the defendants.

Even in victory, the New York Panthers were effectively shut down, as the trial split the group from its parent organization. The fates of the 21 ended up being varied. Afeni Shakur became perhaps the most famous member of the group; at the time of her acquittal sh was eight months pregnant with a child who would become rap icon Tupac Shakur. Afeni and her husband, Lumumba Shakur, had been swept up by authorities alongside the others, and only the pregnant Afeni was allowed bail during the trial.

Various members of the Panther 21 had subsequent legal troubles. Sundiata Acoli was later tried and convicted for the 1973 killing of a state trooper on the New Jersey Turnpike and is currently serving a life sentence. Kuwasi Balagoon was convicted of participating in a 1981 armored truck robbery that left three people dead; he died in prison in 1986 after publishing several influential works on anarchism.

Two defendants, Michael Tabor and Richard Moore, had fled to Africa halfway through the trial, surfacing in Algeria. Though the two men said they left the country for fear of their lives, they were denounced by the Panther’s co-founder and supreme leader, Huey Newton, for abandoning their comrades. By contrast, Jamal Joseph, who later spent five years in prison for harboring another member of the Shakur family, became an academic and writer, earning a full professorship at Columbia University and earning an Academy Award nomination for co-writing a song for the 2007 movie August Rush.

In hindsight, the activities of various authorities against the Black Panthers and other Black activists has come under increased scrutiny. Revelations about the tactics used and popular depictions of these events, such as the recent Academy Award-winning film Judas and the Black Messiah have spread knowledge of the extent to which our own government targeted Black U.S. citizens and organizations.

Given the disparities that exist in the ways in which authorities have responded to movements like Black Lives Matter compared to the light approach against white, right-wing extremists, the relevance of past incidents like the prosecution of the Panther 21 continues to grow.