Until this June, federal law kept people from filing for trademarks of words and symbols that were considered offensive or disparaging.

But when, on June 19, the Supreme Court overturned that law, the gates were opened for all sorts of trademarks.

And enterprising citizens have wasted absolutely no time.

Two of these people, a white lawyer in Alexandria, Virginia named Steven Maynard and a black man in Columbus, Mississippi named Curtis Bordenave have one thing in common: they both want to trademark the n-word.

Steven Maynard, according to WUSA 9, wants to trademark both the swastika symbol and the n-word as weapons against white supremacy.

Despite a death threat, an Alexandria lawyer & company want to trademark swastika. Why? @wusa9 at 6 pic.twitter.com/dtFX6poWIq

— Bruce Leshan (@BruceLeshan) July 24, 2017

"We want to desensitize it. We want to provoke questions. We want to spark conversations and not suppress," Maynard, with his face blocked out, told WUSA 9 in an interview.

Maynard also told Reuters saying that by trademarking the swastika he wants to "turn hate into hope."

"If you suppress it, you give it power," Maynard said.

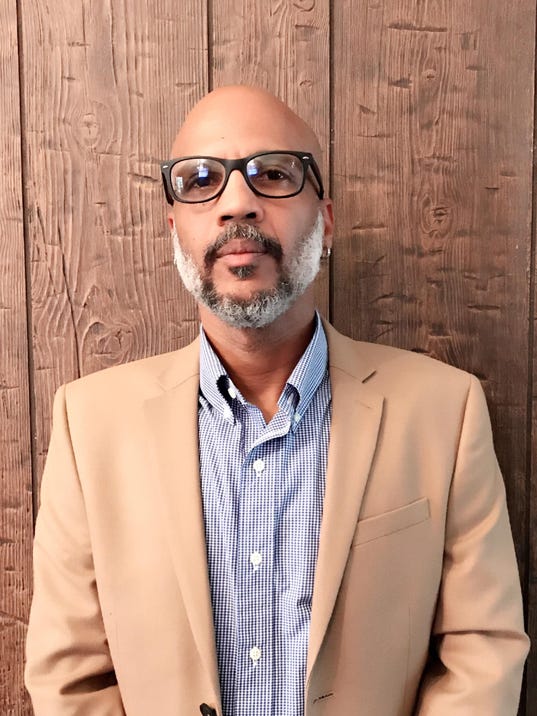

Curtis Bordenave has also filed multiple applications to have the n-word trademarked for commercial use according to The Clarion Ledger.

"We plan on dictating the future of how we define this word," Bordenave said. "A young, black businessman from Mississippi has acquired the rights to the word. I think that’s a great ending to that story."

In order for the symbol and the word to be successfully trademarked, Maynard and Bordenave would have to produce and sell products with the symbol and word on them.

Both men have listed the products they plan to sell with the symbols emblazoned on them on the applications. The items will include clothing, mobile apps, campaign buttons, alcohol and toiletries.

"Because the word is such a well-known word without a brand, without a logo, it actually has the ability to become a famous mark almost instantly," Bordenave said. "Our message is bigger than our brand. Our message is, 'Every shade, every gender unite.'"

The Mississippian says he has already begun to sell t-shirts with the n-word discreetly in the tag.

"I think that we’re taking it and making it good. I think that we can make it positive. I think, for that word, for some reason, people believe you can’t change the meaning of it, you can’t redefine it. To keep it locked away gives it power to the individuals who utter it for negative use," Bordenave said. "But when we define the word clearly, and we give it a powerful strong meaning, then now when you put it on the shirt, we want people to think about the message."

Maynard has a similar motive for the swastika.

"If we get the right to the swastika," said Maynard, "We'd be able to go into any meeting where they're selling swastika-based flags without our approval, we can confiscate those and frustrate the purpose of those white supremacists."

Maynard, a lawyer and — ironically — a former patent examiner, has said white supremacist groups have wasted no time sending him death threats.

Maynard also wants to make it clear that he is neither racist nor a supremacist, insisting "This is not a racist project. It's about provoking discussions. It's about social activism, they'll get behind it."