Written by Adewole S. Adamson, University of Texas at Austin

Melanoma is a potentially deadly form of skin cancer linked to overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays from the sun. Sunscreen can block UV rays and therefore reduce the risk of sun burns, which ultimately reduces the risk of developing melanoma. Thus, the promotion of sunscreen as an effective melanoma prevention strategy is a reasonable public health message.

While this may be true for light-skinned people, such as individuals of European descent, this is not the case for darker skinned people, or individuals of African descent.

The public health messages promoted by many clinicians and public health groups regarding sunscreen recommendations for dark skin people is incongruent with the available evidence. Media messaging exacerbate the problem with headline after headline warning that black people can also develop melanoma and that blacks are not immune. To be sure, blacks can get melanoma, but the risk is very low. In the same way, men can develop breast cancer, however, we do not promote mammography as a strategy to fight breast cancer in men.

This message is important to me as a black, board certified dermatologist and health services researcher at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin, where I am director of the pigmented lesion clinic. In this capacity I take care of patients at high risk for melanoma.

Melanoma in black people is not associated with UV exposure

In the U.S., melanoma is 20 to 30 times more common among whites compared to blacks.

In blacks, melanoma usually develops in parts of the body that get less sun exposure, such as the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. These cancers are called “acral melanomas,” and sunscreen will do nothing to reduce the risk of these cancers.

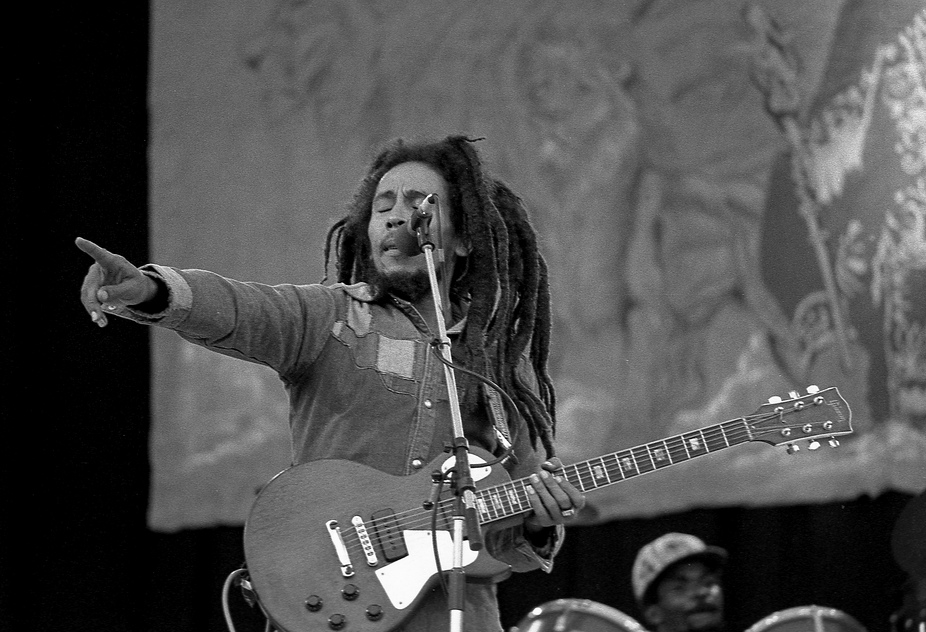

When was the last time you had a sunburn on the palms or soles? Even among whites, there is no relationship between sun exposure and the risk of acral melanomas. Famously, Bob Marley died from an acral melanoma on his great toe, but sunscreen would not have helped.

The research on the association of UV radiation and melanoma among blacks is lacking. Most studies assessing the relationship exclude patients of darker skin types. In the largest study of this question to date, no connection was found between UV index or latitude and melanoma among black people.

Racial disparities in melanoma outcomes are not related to UV exposure

Many dermatologists often point out that black patients tend to show up to the doctor with later stage melanoma, which is true. However, this is an issue of access and awareness and has nothing to do with sunscreen application. Black people should be aware of growths on their skin and seek medical attention if they have any changing, bleeding, painful, or otherwise concerning spots, particularly on the hands and feet.

However, the notion that regular application of daily sunscreen will reduce an already extremely rare occurrence is nonsensical.

Blavitize your inbox! Join our daily newsletter for fresh stories and breaking news.

UV radiation does affect dark skin and can cause DNA damage; however, the damage is seven to eight times lower than the damage done to white skin, given the natural sun-protective effect of increased melanin in darker skin. To be clear, using regular sunscreen may help with reducing other effects of the sun’s rays such as sun burns, wrinkling, photoaging and freckling, which are all positive, but for the average black person sunscreen is unlikely to reduce their low risk of melanoma any further.

If sunscreen was important in the prevention of melanoma in dark-skinned patients, then why have we never heard of an epidemic of melanoma in sub-Saharan Africa, a region with intense sun, a lot of black people, and little sunscreen?

In certain sub populations of black people, such as those with disorders causing sun sensitivity, albino patients, or patients with suppressed immune systems, sunscreen use may reduce risk of melanoma. But if you don’t fall into one of these categories, any meaningful risk reduction from the application of sunscreen is unlikely.

Melanoma public health messaging must change

When it comes to the public health message related to sunscreen, skin cancer, and black people a one-size-fits-all approach misses the mark. The facts simply do not add up for the recommendation of sunscreen as prevention of melanoma in black people. Many dermatology and skin cancer focused organizations (a few of which I’m a member), promote the public health message of sunscreen use to reduce melanoma risk among black patients. However, this message is not supported by evidence. There exists no study that demonstrates sunscreen reduces skin cancer risk in black people. Period.

This issue of regular sunscreen use in black people was made even more pressing after the release of a study last week on sunscreen absorption in the Journal of the American Medical Association. This study showed that significant amounts of certain chemical sunscreen ingredients can get in the blood when used at maximal conditions, with unknown impacts on human health. To me, the most shocking part of the study was that most of the participants were black, the group least likely to derive any meaningful associated health benefits from sunscreen, while being exposed to potentially harmful levels of chemicals.

As dermatologists and public health advocates, we can do a better job educating patients and the public about melanoma prevention, without promoting public health messages that are grounded in fear and/or lack evidence. Black people should be informed that they are at risk of developing melanoma, but that risk is low.

Any dark skinned person who develops a new, changing or symptomatic mole should see their doctor, particularly if the mole is on the palms or soles. We don’t know what the risk factors are for melanoma in black or dark skinned people, but they certainly are not UV rays.![]()

Adewole S. Adamson, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine (Division of Dermatology), University of Texas at Austin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.