Written by Thomas Craemer, University of Connecticut

____

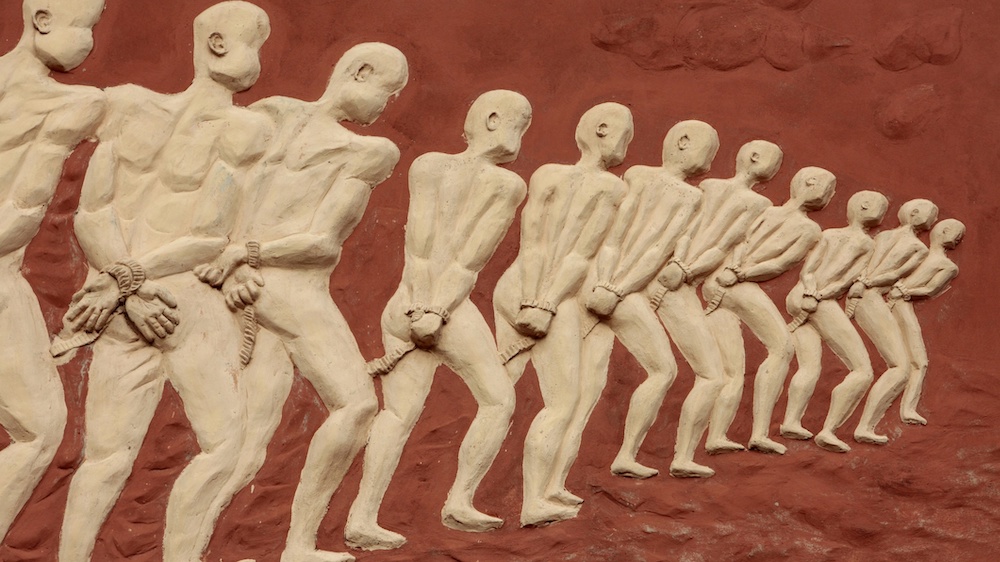

The cost of slavery and its legacy of systemic racism to generations of Black Americans has been clear over the past year – seen in both the racial disparities of the pandemic and widespread protests over police brutality.

Yet whenever calls for reparations are made – as they are again now – opponents counter that it would be unfair to saddle a debt on those not personally responsible. In the words of then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, speaking on Juneteenth – the day Black Americans celebrate as marking emancipation – in 2019, “I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago for whom none of us currently living are responsible is a good idea.”

As a professor of public policy who has studied reparations, I acknowledge that the figures involved are large – I conservatively estimate the losses from unpaid wages and lost inheritances to Black descendants of the enslaved at around US$20 trillion in 2021 dollars.

But what often gets forgotten by those who oppose reparations is that payouts for slavery have been made before – numerous times, in fact. And few at the time complained that it was unfair to saddle generations of people with a debt for which they were not personally responsible.

There is an important caveat in these cases of reparations though: The payments went to former slave owners and their descendants, not the enslaved or their legal heirs.

Extorting Haiti

A prominent example is the so-called “Haitian Independence Debt” that saddled revolutionary Haiti with reparation payments to former slave owners in France.

Haiti declared independence from France in 1804, but the former colonial power refused to acknowledge the fact for another 20 years. Then in 1825, King Charles X decreed that he would recognize independence, but at a cost. The price tag would be 150 million francs – more than 10 years of the Haitian government’s entire revenue. The money, the French said, was needed to compensate former slave owners for the loss of what was deemed their property.

By 1883, Haiti had paid off some 90 million francs in reparations. But to finance such huge payments, Haiti had to borrow 166 million francs with the French banks Ternaux Grandolpe et Cie and Lafitte Rothschild Lapanonze. Loan interests and fees added to the overall sum owed to France.

The payments ran for a total of 122 years from 1825 to 1947, with the money going to more than 7,900 former slave owners and their descendants in France. By the time the payments ended, none of the originally enslaved or enslavers were still alive.

British ‘reparations’

French slave owners weren’t the only ones to receive payment for lost revenue, their British counterparts did too – but this time from their own government.

The British government paid reparations totaling £20 million (equivalent to some £300 billion in 2018) to slave owners when it abolished slavery in 1833. Banking magnates Nathan Mayer Rothschild and his brother-in-law Moses Montefiore arranged for a loan to the government of $15 million to cover the vast sum – which represented almost half of the U.K. governent’s annual expenditure.

The U.K. serviced those loans for 182 years from 1833 to 2015. The authors of the British reparations program saddled many generations of British people with a reparations debt for which they were not personally responsible.

Paying for freedom

In the United States, reparations to slave owners in Washington, D.C., were paid at the height of the Civil War. On April 16, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the “Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service or Labor within the District of Columbia” into law.

It gave former slave owners $300 per enslaved person set free. More than 3,100 enslaved people saw their freedom paid for in this way, for a total cost in excess of $930,000 – almost $25 million in today’s money.

In contrast, the formerly enslaved received nothing if they decided to stay in the United States. The act provided for an emigration incentive of $100 – around $2,683 in 2021 dollars – if the former enslaved agreed to permanently leave the United States.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world.

Sign up today.]

Similar examples of reparations going to individual slave owners can be found in the records of countries including Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, as well as Argentina, Colombia, Paraguay, Venezuela, Peru and Brazil.

The French government even set an example on how the government can conduct genealogical research to determine eligible recipients. It compiled a massive six-volume compendium in 1828, listing some 7,900 original slave owners in Saint Domingue and their French descendants.

Reparations, this time the other way round …

Blessed with detailed U.S. Census records and local archives, I believe the government could do the same for the Black descendants of enslaved Americans.

In the 1860 census, the last one before the Civil War, the government counted 3,853,760 enslaved people in the United States. Their direct descendants live among close to 50 million Black residents in the United States today.

Using historic census records to estimate the number of man-, woman-, and child-hours available to slave owners from 1776 to 1860, I estimated how much money the enslaved lost considering the meager wages for unskilled labor at the time, which ranged from 2 cents in 1790 to 8 cents in 1860. At a very moderate interest rate of 3%, I arrived at an estimate of $20.3 trillion in 2021 dollars for the total losses to Black descendants of enslaved Americans living today.

It is a huge sum – roughly one year’s worth of the U.S.‘s GDP – but a figure that would comfortably close the racial wealth gap. The difference is, in contrast to historical precedents, this time the benefits would go to the Black descendants of the enslaved, not to enslavers and their offspring.![]()

____

Thomas Craemer, Associate Professor of Public Policy, University of Connecticut

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.