If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

Close your eyes and picture this: You’re 16 years old, living on your estate with your happy family. Your melanin is poppin’, fro so nice Angela Davis would stan, riding motorbikes with your best friend and cousin, Adjoa — life is good. And in a blink of an eye, you’re forced to abandon everything and go into hiding with your best friend’s father’s family, eventually seeking refuge in a foreign land, where you are viewed as an “other” during the Reagan administration, when the “others” were brutally targeted.

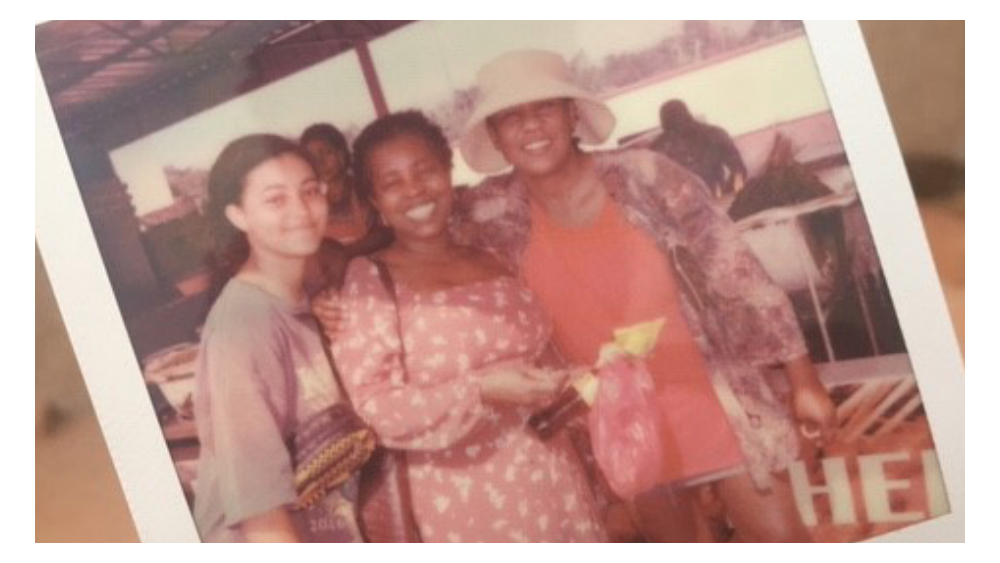

Now open your eyes, take a deep breath and be thankful that is not your life. But it was my mom’s. My mom came to the United States from Ghana in 1985, after my grandfather, who was a government minister before the coup in 1979, was forced to leave the country, or lose his life. Between 1979 to 1985, my mother sought refuge with my aunt Adjoa’s family. This strengthened a familial bond that was already generations old. (Starks and Baratheons, who?)

Fast forward to 2019, the year my grandmother turned 75. When we asked her what she wanted for her birthday, her first choice was great-grandchildren. Her second choice was to return home and see her 10 brothers and sisters who she had not seen in 34 years. So naturally, my mom and I began looking up flights.

Once my mom told my aunt Adjoa we were thinking about going back to Ghana, boom, pan-africanism. OK, not exactly, but suddenly this trip was more than just a family vacation. This was the chance to answer 34 years of questions. My mother and my grandmother, with the help of my aunties (shoutout to all the Black women playing both mom and dad to their kids), got me to where I am today. I was determined to support them in whatever way possible. Getting to go to the Afro Nation festival, held on Laboma Beach in Ghana from December 27 to December 31, with my cousins and family friend, Chineze, was the full circle icing on the proverbial cake. Little did I know that I was taking a 10-hour Delta flight to realize my ignorance. Oh joy.

Being a dark skin Black man who grew up in New York, I know racism just as well as I know the words to “Hypnotize” by Biggie. The “cultural melting pot” that is New York City and the white dominated suburbs that surround it were the perfect breeding ground for segregation and ignorance. My racial identity is something I have always struggled with.

I spent the first half of my childhood in East New York. My mom, growing more nervous about the crime in our neighborhood, moved us upstate to Chester, New York, where there were approximately three more deer than Black people. I spent my childhood literally going from being too white for the Black kids, to too Black for the white kids. I found safe spaces in my few close friends, who still ride for me today, and told myself, “in college I would figure myself out.”

So, about that.

When I got to college and was exposed to various different identities within the Black diaspora, I was still at a loss for where I fit in. Despite how diverse our community is, sometimes the only thing that is focused on is “black.” As a result, we set certain parameters detailing what Black people should and should not do. In the process of that, we isolate those who do not fit that mold.

In the post-civil rights era, the influx of African immigrants has made the diaspora even more complex. What I mean by that is there are major differences between being a Black American, an African American and an African immigrant residing in America. However, often times those terms are used to describe us interchangeably, ignoring our historical differences and cultural capital.

Now ask yourselves, do we in the community do this as well?

The Black community needs to come together for survival, point blank. If the years following Trayvon Martin’s murder have taught us anything, it is that the first step that those who wish to destroy us will take is to divide us. However, that does not mean that we cannot respect each others’ differences in the same way we expect the white community to respect our differences.

An Ethiopian immigrant who moved to the U.S. in 2015 might have literally nothing in common with a Black dude from Savannah, Georgia — who can trace his family line in the U.S. back before the civil war — other than the fact that they are Black. In our search for allies, we have tiptoed the line between African appreciation and African appropriation.

And then my best friend, Jackie, blessed me with her typical brand of Black girl magic when in regards to the Botham Jean murder she pointed out how wild it was that white America brought us here against our will and now does not really want us here. (And for white people reading this and saying, “not all white people,” in their minds, of course that’s true. But please hush. You have had 400 years to speak.)

When Jackie said that, I literally had the wind knocked out of me like Mariah Carey during that whisper note on any of her songs. Finally I understood. Black Americans do not take on African culture as their own as a means of appropriation, but as a means of rediscovery. I have the privilege of knowing exactly where in Africa my family originated from. Many of my friends, thanks to slavery, are not as lucky. Though the frequency has increased in recent years, trips back to Africa have been popular since the civil rights days.

When Malcolm X visited Egypt in 1959, one thing he commented on was how the land seemed to be absent of race. Like many, Malcolm X was under the impression that a lack of racial diversity equated to a lack of racism. Sorry, but no. Now, before y'all drag me for calling Malcolm X problematic, this particular view is problematic.

The United States is known for its ethnocentric view of the world. The idea of American exceptionalism promotes a culture in which many Americans believe that we are the center of the world. I hate to say it fam, but I think the Black community has adopted this mindset in terms of Black marginalization. Malcolm X is on the Mount Rushmore we would actually visit for many people of color, including me. However, do not be deceived into believing that racism doesn't exist outside of the Western world. Racism, colorism, sexism and privilege, though they may take different shapes, are universal.