If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

At this point in election season, you've probably seen hundreds of voter registration ads, explainers on filling out your mail-in ballot and reminders to vote from friends, strangers and Instagram influencers.

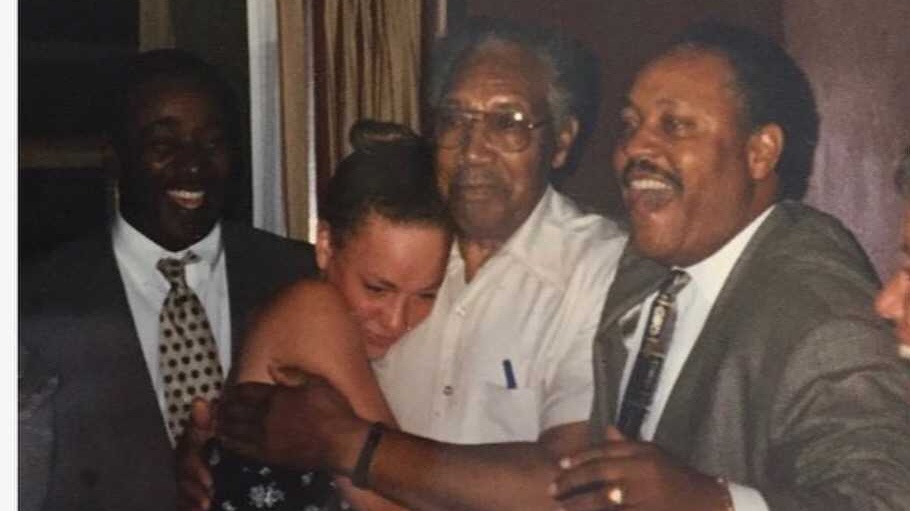

One of those messages might have been from me — or my mom, dad, cousins, friends or colleagues. For my family, civic engagement has never been an optional activity. That’s because we know our right to vote is precious and fragile.

At age 34, my grandfather was the first person in my family to vote. Unlike other Americans, he wasn’t allowed to vote simply by turning 18. He couldn’t earn his vote by being a good citizen, working hard in a Sears’ warehouse and paying all his taxes. He couldn’t vote even after serving under General Patton in World War II and jumping off a ship into 10 feet of cold water on the third day of the Normandy invasion.

Like his father who served in World War I, my grandfather came home to a country that used a grab bag of tactics — from poll taxes to police intimidation — to prevent him from voting because he was Black. The message was clear: he could fight alongside his fellow soldiers in war, but he could not stand alongside his fellow citizens at the polls.

For my great-grandmother, the barrier was South Carolina’s literacy test, which required people to demonstrate they could “read and write a section of the state constitution” before being allowed to register to vote. Born to a family of sharecroppers, she worked outside every day while other children attended classes. Later in life, she took a job as a cleaner in an all-Black high school. The teenage students taught her to read and to write her name, which she signed on the first ballot she cast in 1968, three years after the Voting Rights Act outlawed literacy tests.

The 1965 Voting Rights Act prohibited racial discrimination in voting and gave my grandparents and great-grandparents their first opportunity to cast a ballot; but my family’s work wasn’t finished. As a child, I watched my mother and father pack the car to drive people to the polls, register hundreds of voters and serve as poll watchers and commissioners.

As lawyers, my parents fought state officials attempting to purge voter rolls. As neighbors, they escorted anxious elderly voters past police cars, lights flashing, parked in front of polling stations — as if Black people voting was a crime in progress.

We cannot honor our ancestors without exercising the rights for which they fought. Yet in the 2016 presidential election, 100 million eligible voters didn’t participate. 43% of the electorate stayed home. And Black voter turnout declined for the first time in 20 years.

Today, as the first Black CEO of Vote.org, I’m leading efforts to make sure everyone votes in 2020. This year alone, Vote.org has registered more than 3.3 million voters, helped more than 3.1 million voters request mail-in ballots and verified voter registration for 8.2 million people.

We’re using technology to simplify civic engagement, increase voter turnout and strengthen American democracy — but voting is still a fragile right for too many Americans. This year, the COVID-19 pandemic threatened to keep millions of elderly, at-risk or marginalized people from voting. To request a mail-in ballot, states like Alabama require voters to print, sign and mail an application, disproportionately impacting people without access to a printer.

Vote.org worked fast to develop tools to print and mail ballot request forms directly to voters. Any eligible voter can contact Vote.org and within a few days receive their printed application, along with a postage-paid envelope to return the form to their local Election Manager. By providing paper forms, envelopes and postage, we’ve helped millions of voters secure a mail-in ballot over the last few months.

As I work to make sure everyone can vote this year, I’m thinking of Congressman John Lewis, of voter registration workers like Reverend George Lee and Lamar Smith who were murdered in Mississippi in 1955, and of my own family who, in so many ways, fought for the freedoms I have today.

In their honor, I have to ask again: Do you have a plan to vote?

Maybe you, like my grandfather, will become the first voter in your family when you cast a ballot this year. And I’ll be here to protect your rights, in this election and the next one.

____

Andrea Hailey is the CEO of Vote.org and founder of Civic Engagement Fund.