If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

On December 4, 1969, one of the country’s most promising young revolutionaries was murdered by police, in a joint operation fully supported by the FBI. That revolutionary’s name was Fred Hampton, and 50 years later his brief time in the spotlight still evokes admiration and deep regret over the events that took his life.

Hampton was just 21 years old when he was murdered in cold blood, while he lay sleeping beside his fiancée in his apartment on Chicago’s West Monroe Street. Despite his youth, Hampton had already risen to become head of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP).

Everyone who knew Fred Hampton, or knew of him, was sure he was destined to accomplish great things. But in the minds of some powerful actors, those great things were feared rather than anticipated. Ultimately, it was Hampton’s fierce determination to fight against the racism and inequality that cost him his life.

My Personal Relationship with the Black Panther Party

Race was an ever-present topic in my home. My mother was African American and Japanese, and my father was white. After they were married in New York City in 1960 (seven years ahead of the SCOTUS decision to legalize interracial marriage on a national level), my father’s family disowned him. My parents made the decision to raise my two brothers and me to self-identify as Black, as opposed to Biracial or mixed race. This even applied to me — the lightest in complexion of the three of us.

Odd as this may seem to Biracial and Multiracial people half my age, this wasn’t all that uncommon in the 1960s and ’70s. Without exception, all of the kids in my neighborhood whose parents were different races were raised to identify with the more oppressed race.

I first became aware of the Black Panther Party when I was four years old. My parents separated in 1969 (when I was three), and sometime in the early months of 1970, my mother filed for divorce. Soon after, she began a relationship with a member of the New York chapter of the Black Panther Party.

My mother’s boyfriend, Al* (who joined the Black Panther Party in 1968) lived with us and he had a profound impact on my identity as a woman of color — more so than my well-meaning and supportive father could have had on his own. Although my parents were raising us to self-identify as African American, I don’t think the direction my mother took with our identity made my father entirely comfortable.

While my father always considered himself an ally to the Black community (and he was, believe me), when my mother stopped relaxing her hair, encouraged my oldest brother (who was then seven) to grow out an Afro, began teaching my brothers and me the Black Power salute, and started talking about how the “The Man” was subjugating Black people, I think it was a little much for him.

By the time I was four years old, I was aware of racism, despite its complexities, and I understood why the BPP had to be formed (although I can’t say I knew as much about Fred Hampton as I did about Huey Newton, Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver). I was both saddened and intrigued when Al talked about who Hampton was and why he was murdered. However, to be honest, I don’t think I really understood how much and exactly what we had lost (and the bourgeoisie gained) with the murder of Fred Hampton — not until the rebellions across the country following the Rodney King verdict in 1993. By then I was 26.

I saw how Hampton’s murder continued to impact our myriad, often grave (but seemingly futile) efforts at equality. Nowadays, every time I watch the video of Rodney King being beaten or read about another brother or sister harassed and/or killed by cops — usually with no indictment or conviction — I know we lost so much more than a young man with a promising future.

Who Was Fred Hampton?

Almost from the minute it was formed, the Black Panther Party was under siege from law enforcement. Their assertive, uncompromising stance against discrimination, their embrace of so-called “radical” politics and their commitment to community organizing made them a serious threat to the status quo — one that certain establishment figures and their armed henchmen were determined to stamp out. No one was more paranoid and hostile to the Black Panthers than FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, who launched a campaign of sabotage and terrorism against the organization. This campaign was fully backed by most local police departments and district attorneys’ offices — including the one in Cook County, where the city of Chicago is located.

Of them, Hoover described the Black Panther Party as, “without question … the greatest threat to internal security of the country.”

The FBI’s campaign to demonize, demoralize and devastate the Panthers hadn’t succeeded completely, as the organization was continuing to attract idealistic young African Americans to the cause. But by 1969, the three most well-known Panther leaders — Bobby Seale, Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver — had all been taken out of commission, and the Panthers’ need for new blood was undeniable.

Fred Hampton was more than ready to step into the void. A pre-law student from the Chicago suburb of Maywood, Hampton began his civil rights work as a youth organizer for the Chicago-area NAACP before joining the Panthers. Hampton was drawn to the Black Panthers by their fierce stand against police brutality, their charitable works and their unwavering commitment to constructive change through grassroots organizing.

It was evident to anyone who met Hampton that he had something special right from the beginning, and his impact on the fledgling Illinois Black Panther chapter was substantial. As a street-level organizer, recruiter and communicator par excellence, Fred Hampton made a positive impression on almost everyone who met him.

“He had such courage and charisma, it's hard to believe he was so young,” remembered Bobby Rush, a Congressman from Illinois who started that state’s Black Panther chapter. “And he was such a public speaker. There was a kind of quiet competition between him and Jesse Jackson back in 1969.”

One of Hampton’s most impressive acts as a Panther was his success in negotiating a truce between several of Chicago’s most powerful gangs. He wanted gang members to lay down their arms and reach out their hands to form a multiracial alliance, which would dedicate itself to community and political activism. Hampton referred to his group as the “Rainbow Coalition,” a name that was later repurposed by Jesse Jackson during his 1984 presidential campaign.

“Fred Hampton knew that he could organize anybody,” explained Hampton’s fiancée, Akua Njere (née Deborah Johnson), in a 1990 interview. “He talked to the brothers and sisters on the street. He talked to those in the classroom. He talked to those in the factories. He talked to those who were in business. He went to the churches. He organized and attempted to work with every element of our communities.”

On the ideological side, Hampton had made his feelings about capitalism and its historical effect on the Black community clear, in a speech he gave in 1968.

“Capitalism comes first and next is racism,” he declared. “When they brought slaves over here, it was to make money. So first the idea came that we want to make money, then the slaves came in order to make that money. That means, through historical fact, that racism had to come from capitalism. It had to be capitalism first and racism was a byproduct of that.”

From the standpoint of the establishment, this type of talk was enough to set off a panic. A Black Panther Party committed to ending institutionalized racism was bad enough. But a Black Panther Party that was ready to fight against racism and capitalism simultaneously? That was absolutely terrifying, and the idea of Fred Hampton rising to a position of leadership in the Black Panthers undoubtedly caused a lot of anxiety among those who viewed the Party as a hostile alien force. Like FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and his field agents in the Chicago area, for example.

Despite his seemingly young age, when Illinois BPP founder Bob Brown left the organization in 1969, Fred Hampton was named the new chairman. While continuing to speak and organize and recruit, as Panther leader he led weekly self-empowerment rallies, introduced people to radical politics during daily 6 am education classes, started a community program to monitor police activity and helped expand the Party’s free breakfast program.

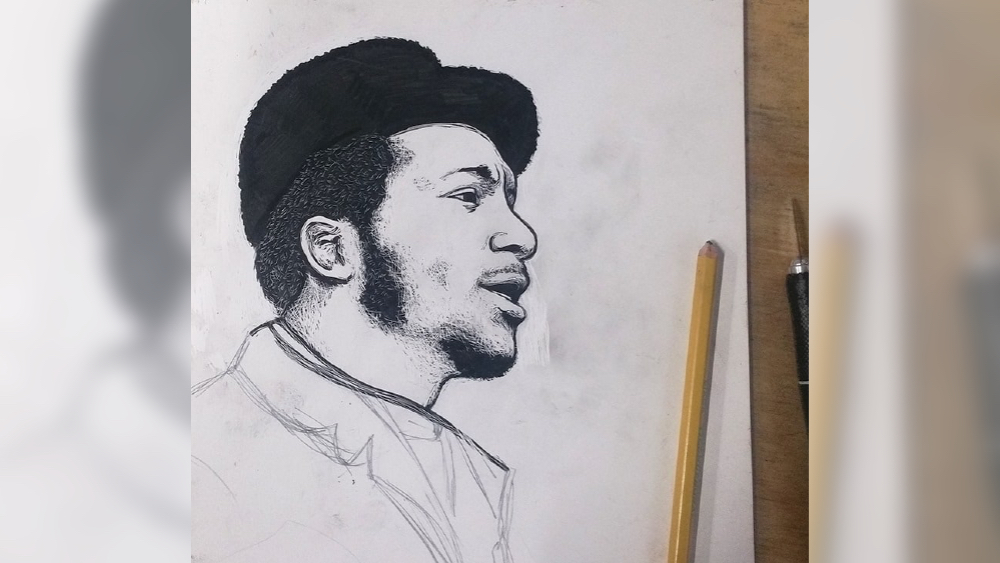

Fred Hampton with "Doc" Satchel in a meeting with prospective partners.

Word of his success reached National BPP Headquarters, and he was flown to Oakland to meet with national leaders who were anxious to learn more about this energetic bridge-builder who was shaking things up in the Midwest. Like everyone else they were impressed, and by that time there was no doubt that Fred Hampton was being groomed for a high position in the Party at the national level. Unfortunately, he never got the chance to fulfill that destiny.

The FBI Vendetta Against Fred Hampton, and Its Tragic Consequences

The FBI’s war on the Black Panthers was motivated by J. Edgar Hoover’s pathological racism. Hoover was an autocrat and a control freak, and his virulent attitudes warped the hiring and promotional practices of the Bureau and ensured its enmeshment in bigotry and hatred. Hoover was also notoriously paranoid about communism, and Fred Hampton’s open and unapologetic embrace of Maoist principles undoubtedly speeded his rise to the top of the FBI’s hit list.

Mimicking the CIA and his friends in organized crime, Hoover was more than willing to exceed his mandate and implement secret conspiratorial operations designed to destroy his political enemies, through false imprisonment or assassination.

Check out the first sentence in bullet point 2.

In a secret document distributed to FBI field offices on August 25, 1967, Hoover explained the objectives of his anti-Black Panther Party COINTEL (counterintelligence) program. FBI agents were instructed to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of Black nationalist hate-type organizations and groupings, their leadership, spokesmen, membership and supporters, and to counter their propensity for violence and civil disorder."

One effective way to do this was through the use of infiltrators. These were federal agents or paid informants who would join BPP chapters in different cities, and then supply information to the FBI about their plans and activities. Many of these infiltrators acted as provocateurs, encouraging others in the group to engage in illegal and violent acts that would discredit them and leave them vulnerable to arrest and prosecution.

This strategy was used on the Illinois Black Panthers, and with great effectiveness. The FBI recruited an unsavory character named William O’Neal to infiltrate the group, and he proved to be the ideal choice (from their malicious perspective). O’Neal ascended to the position of Chief of Security for the Illinois chapter and ironically was selected as Hampton’s personal bodyguard—a job he had no intention of actually performing.

With inside access secured, O’Neal was able to provide his FBI handlers with detailed information about Hampton’s movements and habits, and about the physical layout of Hampton’s apartment. This information was eventually passed on to the Cook County District Attorney’s Office, which conspired with the FBI to set up the raid that would cost Fred Hampton his life.

Despite a decade of social unrest, in the late 1960s local, state and federal police agencies were generally still under the control of reactionary elements. With little concern for the Constitution or the Bill of Rights, they were determined to stamp out the Civil Rights Movement, the anti-war movement and any other progressive movement seeking to change America for the better. This was certainly true in Chicago, where the attitudes of Hoover’s FBI were fully shared by prosecutors, the mayor’s office and local police.

Cook County District Attorney Edward Hanrahan

Anti-radical sentiment—along with a degree of political calculation—undoubtedly motivated the actions of Cook County District Attorney Edward Hanrahan, who authorized the raid on Hampton’s apartment. Hanrahan was a protégé of Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, the leader of the corrupt Democratic machine that controlled Chicago politics at that time. Despite his identification as a Democrat, Daley was a right-wing racist with no interest in or sympathy for social justice. Under his administration, the Chicago Police had a free hand to battle communists, Black activists, long-haired subversives and anyone else who, in Daley’s excuse for a mind, rocked the boat and were a danger to the public order.

In total, 14 police officers attached to the Cook County District Attorney’s Office were dispatched to Hampton’s residence on West Monroe Street in the pre-dawn hours of December 4. Supposedly, they were there to seize a cache of allegedly illegal weapons stored in the apartment. But in reality the raid was a planned hit, with Hampton the prime target for assassination.

After eight of the 14 officers busted down the door of the apartment, they burst in with guns blazing. In their later testimony, the cops tried to blame the Panthers for starting a firefight. But forensic analysis proved the cops had fired more than 80 shots, while only one bullet could be traced to the gun of a Panther. The latter came from a shotgun carried by Hampton associate Mark Clark, who had been sleeping in a chair (on guard duty) when the police stormed in, and he apparently squeezed the trigger in a death reflex after he was killed by a shot to the heart.

Six people were hit by police bullets in the dark apartment, two of whom were killed: Clark and Fred Hampton. Acting on information received from the FBI informer, O’Neal, the cops aimed their fire at the wall of a bedroom where they knew Hampton was asleep. The night before, O’Neal had slipped a knockout drug into Hampton’s drink, guaranteeing his unresponsiveness during the home invasion.

Fred Hampton's fiancée, Akua Njere, talked with a reporter about the night Fred Hampton was killed. She was lying next to him in bed. Both were sound asleep when the cops killed Hampton.

Eventually, two cops barged into Hampton’s bedroom, where they found him wounded and unconscious. Lyingeside Hampton, too frightened to move, his fiancée Akua Njere heard one of the officers ask the other, “Is he dead?” In response, the other policeman took out his revolver and fired two shots into Hampton’s head.

“He’s good and dead now,” the uniformed assassin announced.

When word spread that Hampton had been killed, cheers were heard coming from multiple locations over the police radio, as officers in squad cars around the city reacted to the death of an idealistic young man they’d arbitrarily chosen to hate.

A Devastating Loss for the Black Panthers, and for America

The wheels of justice often turn slowly, when they turn at all. Then as now, the legal system seldom held cops responsible for their homicidal actions, especially when the victims were people of color.

But what happened in the case of Fred Hampton was so egregious that eventually the truth had to come out. After years of legal battles, and acquittals for District Attorney Hanrahan and 13 officers involved in the raid, in 1979 a federal court finally issued a ruling in favor of the slain, which led to large settlements paid out to the families of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark.

FBI involvement in the murders of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X has long been suspected. But smoking gun proof has remained elusive. This is not the case, however, with the murder of Fred Hampton. Extensive investigation uncovered the truth about the collusion between corrupt G-men and the ambitious Cook County prosecutor, Hanrahan. Without FBI intervention there likely would have been no raid, and Fred Hampton might still be alive today.

And that could have changed the course of history for the Black Panther Party, and for America. Fred Hampton as a Black Panther leader would have pursued a radical but inclusive path. He would have sought to expand his burgeoning alliance of freedom fighters, to create the unity and strength in numbers that it takes to achieve real change in this world.

“Marx and Lenin and Che Guevara and Mao Tse-tung and anybody else that has ever said or knew or practiced anything about revolution always said that a revolution is a class struggle,” Hampton proclaimed in 1968. “It was one class – the oppressed, and that other class – the oppressor. Those that don't admit to that are those that don't want to get involved in a revolution.”

After Hampton’s murder, membership in the Illinois Black Panthers declined rapidly, and his Rainbow Coalition gradually dissolved. Ultimately, this foretold the decline of the Black Panthers on a national level, and the dissolution of the youthful energy and idealism it embodied.

When Fred Hampton died, a promising moment in time died with him. His vision for the Black Panther Party was both revolutionary and evolutionary. Under his inspired leadership, I have long speculated that his Rainbow Coalition could have facilitated the fusion of civil rights with the search for economic justice, creating a unified yet diverse army of activists ready to challenge the status quo and the existing arrangements of power.

They may have succeeded, or they may have failed. But they could have shaken a fundamentally corrupt system to its core, motivating future generations to take up the struggle and perhaps eventually bring us to something approaching actual equality.

My mother and Al broke up in 1972, and my parents reconciled soon after. Despite being only 6 years old at the time of their breakup, these days I frequently find myself reflecting on the truths and wisdom Al imparted to my brothers and me about politics, race and racism, and I know we lost a leader, a visionary and quite possibly the last chance at complete equality I’ll see in my lifetime.

With the exception of the featured image, all photos and facts courtesy of the documentary The Murder of Fred Hampton, directed by Howard Alk and released in 1971.

Featured image illustration credit goes to Ricardo Levins Morales. Thank you for allowing me to use it.

____

Sarah Ratliff is a corporate America escapee turned organic farmer, writer & published book author. She does content marketing and bylined writing.