“Not seeing color” is not a prerequisite for equality.

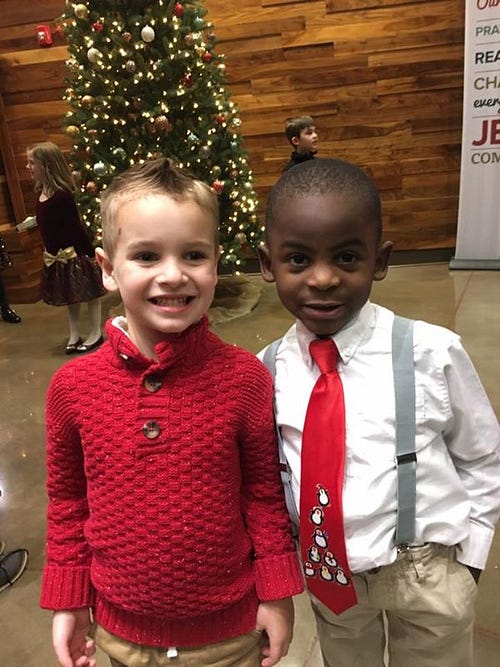

About a week ago (a week ago), a story about two preschool boys who devised a plan to trick their school teacher by getting similar haircuts took the socialsphere by storm. What's so unique and ingenious about this plan was that the two boys (photographed above) are of different race and ethnic background. One, Reddy Weldon, is black and the other, Jaxon Rosebush, white. The young Jaxon has been credited with devising the plan and was quoted saying “We’ll look just alike, she won’t be able to tell the difference between the two of us!” The media was so absorbed in the “cuteness” of an absolutely, one-hundred percent, colorblind white boy wanting to adopt the hairstyle of his black friend, that they followed the two best buds to a salon with reporters and a full camera crew. In a facebook post sharing the photo above, Jaxon’s mother, Lydia Stith Rosebush, stated: “If this isn’t proof that hate and prejudice are something that is taught I don’t know what is. The only difference Jax sees in the two of them is their hair.”

Aside from the media’s coverage of the story, which centers little Jaxon Rosebush and his plan to trick his teacher while referencing Reddy simply as the buddy-accomplice to the plot, I have a few concerns with what the larger narrative represents. And, in earnest, I am, in some way, projecting my own lived experiences onto the friendship of these two boys but with good reason. In some ways — minus the whole being adopted from the Congo and being raised by white parents thing — I see myself in Reddy. If you dig through my old family photo albums you will likely find similar images of me with a full grin, shouldered up with one of my white childhood besties. Hell, if you swipe back a few facebook photos you will find one. However, it would be a mistake to assume that either boy, Reddy or Jaxon, is completely blind, impartial, or impervious to the differences between them. To this day, I still remember one of my childhood friends innocently asking me why my gums were dark and not a bright pink like hers. I still remember the deep-seated frustration that bubbled within me when I failed to produce an answer. I have never forgotten how seamlessly, memories of laughter with some of my white childhood friends have been replaced with memories of their silence in times when their voice would’ve spoken volumes. I have never forgotten the swiftness wth which my elementary school teacher pegged me the instigator after turning around to the commotion of my non-black friends roughhousing in front of me in line awaiting recess. I am ever reminding myself of the many ways in which the innocent in this life may be alienating at best and violent at worst.

Me writing this is in no way to shame these children, their parents, nor the people who found this story adorable. They’re cute kids. In a follow-up interview, Jaxon’s mom, Lydia Stith Rosebush, admits that “deep down inside .. [Jax] absolutely notices there are differences in skin color,” and that he "does not care and the only difference to him is their hair doesn’t match." The problem is: what is hair if not dead skin (and a lil’ keratin)? And, even with the cut, their hair will never “match” in the sense of achieving a sameness. That is a bold truth — a reality that must be seen and embraced in whole, rather than figuratively ignored in part. Both of the five-year-olds, even in their youthful naiveté, are already able to discern a visible difference between one another. They simply do not, yet — for better or worse — know it by the name of ‘race’. And while I even agree with Reddy’s father that “there’s an innocence children have” that we often lose, and that as a society it would be nice to reclaim aspects of that lost innocence, I find there to be something dangerous about espousing a specific narrative that safeguards a type of (white) imagination that allows a (white) child to believe that by merely imitating someone from another racial group or by adopting their aesthetic, he/she is able to escape his/her own positioning, privilege, and penalty in the world.

It is my hope that Reddy and Jaxon’s gleeful and pure friendship will grow and evolve into a true camaraderie — into a brotherhood founded in a loving understanding of one another’s differences and an ownership of the bound liberation required to truly see beyond them.