Conversations about policing have taken the mainstream stage throughout history, from its not-so-humble beginnings in slave patrols, to the sociological concerns that the role feeds the school-to-prison pipeline, to various inequities in staffing and community presence.

There are also present-day stories like that of U.S. Capitol Police Officer Harry Dunn who faced off with Trump supporters on Jan. 6, or Louisiana Sheriff Deputy Clyde Kerr III, who denounced

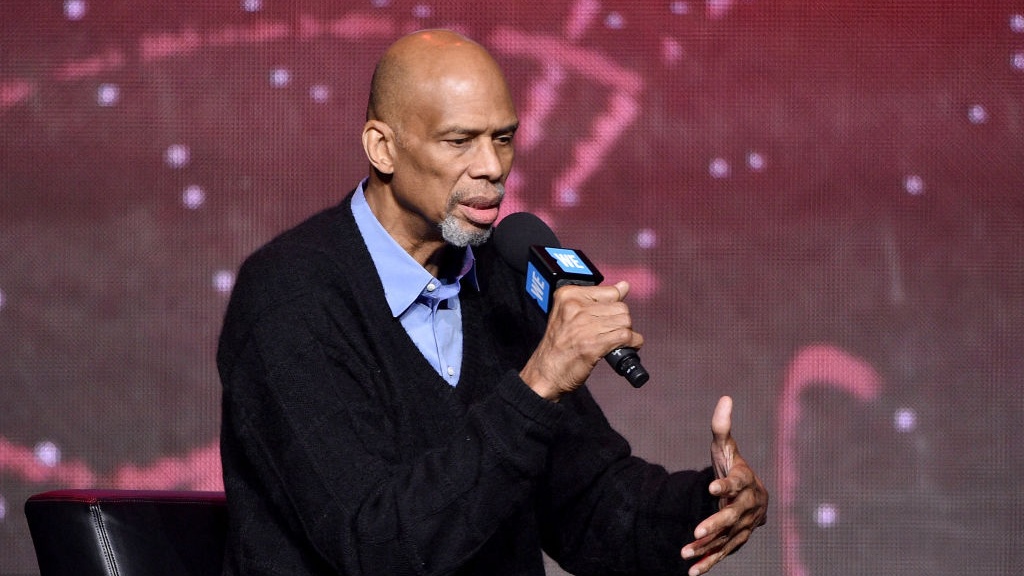

police brutality and racism before taking his own life. The intricacies of being a Black officer in America can be puzzling, troubling and conflicting. NBA Legend turned writer Kareem Abdul-Jabbar explores some of these ideas in his new essay for Amazon Original Stories, Black Cop’s Kid.

"Being a Black cop’s kid made me especially sensitive to injustice," Abdul-Jabbar wrote in his essay.

Most widely known for his amazing basketball career, Abdul-Jabbar's story starts in New York City, when he was the son of an NYPD officer during some of the country's most trying times. Now, the NBA record-holding all-time leading scorer never misses an opportunity to speak out against injustices. He calls these opportunities tributes to his father's legacy, which he honors through his writing.

"As a young athlete, I wanted to achieve a status as a great player," Abdul-Jabbar told Blavity. "I had opinions then and wasn’t afraid to express them, though I didn’t have the same confidence in my words then as I did in my athletic abilities. Now, though, I am confident in my ability to articulate my opinions with the same grace and force that I once had on the court. As an athlete, my job was to entertain the fans. As a writer, my job is to entertain and inform, to use my words to try to make the world a better, more just place where people experience more joy than fear, more love than hate."

In Black Cop’s Kid, he eloquently explores the contrasts of learning about his father's experiences as an officer and being a curious Black child during an era of widespread unrest, including the Harlem riot of 1964, which was stirred up by the police killing of a 15-year-old Black boy, James Powell. Having received the opportunity to join a press pool interview with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Abdul-Jabbar recalled heading to the famous 125th Street to do some jazz record shopping before making his way to a social justice-related meeting, but that as soon as he exited his train stop, bullets rang out. He was 17 years old.

"As I ran that night in fear for my life, it was hard to remember the admonishments for peace from Dr. King," Abdul-Jabbar wrote in the essay. "Mixed in with my fear was anger and frustration — and the knowledge that I would never feel safe again. What kept coming back to me was that man in the crowd shouting back at the cop in anger and frustration, 'We are home, baby!'"

"That outcry resonated throughout my body like a wailing jazz saxophone rattling my bones. We were trying to define what home meant to us, not what it meant to them," the 74-year-old continued. "What our values were, not what they told us we should value. Mostly, home meant being safe — from criminals and from cops. And when we expressed our fear and frustration about any inequities, we were told to 'move on.'"

Abdul-Jabbar contends that night was among the most significant events of his life.

"America sometimes treats Black people the way a neighborhood of homeowners treats renters, as if they are temporary and therefore have no say in the workings of the neighborhood. They need to realize this is our home, not just for us but for our children and for the generations to come," Abdul-Jabbar told Blavity, in reference to that pivotal message he received that night in 1964.

He dedicated himself to relaying that messaging as he got older. The fight for justice stopped being hyper-personal, and has long since led him to use his platform to strike against injustices of all kinds.

"When I was young, I was focused on the injustices to Black people because I constantly felt the sting of it," Abdul-Jabbar said. "It was personal. But as I got older, I saw that it wasn’t just Black people who suffered from injustice, it was women, LGBTQ+, immigrants, Muslims and others. I came to realize that the fight for equality had to include everyone or no one would succeed."

This is why he said he never truly feared the dimming of his NBA stardom when he spoke out. But most importantly, he also recognized that while his celebrity kept him from such harm as police injustices, others haven't been so lucky.

"I don’t generally feel fear from cops because I’m recognizable enough that I’m protected by the mantle of celebrity. Also, because of my dad, I have an innate appreciation for the hardships of their job," he told Blavity. "I like to think the best of people, which means I like to think that most cops choose the job out of a sincere passion to help people. But systemic racism is an infection that corrupts even the healthiest bodies. We all have to fight daily against our base instincts, but systemic racism gives permission and support to some to give in. That’s why, even though I’m less worried about myself personally, I’m very worried for the young Black men and women on the streets every day and the dangers they face."

Abdul-Jabbar spoke out after LeBron James was told to "shut up and dribble'" and encouraged athletes to stand firm on important beliefs. And he refuses to draw any comparisons between himself and current athletes as he said such comparisons do a disservice to them.

"They are their own person with their own approach. There are many players just as motivated to improve society as they are to win a championship," he said.

However, the basketball legend has also remarked on disappointment that some athletes don't stand on their platforms for the best causes.

"NPR did a story about a middle school teacher who couldn’t convince his students that the Earth was round because NBA player Kyrie Irving had said there wasn’t enough evidence to prove it was," Abdul-Jabbar continued. "Instead of using his fame to inspire students to greatness, he dumbed them down."

"This is bad for all athletes because it perpetuates the dumb jock stereotype. Contrast that to athletes like Muhammad Ali who risked everything — his career, his life — to defy the draft," he went on. "If I had to pick an event that motivated me to commit to social justice, it was my participation in the Cleveland Summit when I was 20. Being a part of a group of athletes so passionate about doing the right thing for their people was life-changing."

The outspoken seven-footer said he hopes the world will be a little fairer because of him, saying that the number one thing he wants for the world after he passes on is more opportunities for people — job opportunities, better health care and better education. But first, he has some advice to challenge what he referenced in his essay as "Band-Aid solutions to a systemic disease."

"It has to start with ensuring equality in voting," he told Blavity. "Republicans have come to realize they are struggling to win elections because they offer no ideas for the future, only fear. So, they’ve tried to dilute Black votes through gerrymandering and make it harder for Blacks to vote through legislation. That is a direct attack on democracy, which is why China and Russia’s hackers work so tirelessly to support them. There’s no more need for a military strike by our enemies when they can achieve greater damage on the internet."

In the meantime, Abdul-Jabbar plans to continue writing, particularly by way of a direct-to-fan blog via Substack where he can write whatever he wants without waiting for a publisher. He even recently used the platform to write about his favorite music genre, jazz, and two jazz singers he called impressive — Jazzmeia Horn and Veronica Swift.

"I love writing for different publications because I am able to reach different audiences. The downside was some only wanted me to write about sports, others only about race. Sometimes I write about social issues, but I also do a 'Weekend Boost' every Friday in which I recommend music, books, TV shows, movies or whatever else I think my readers might enjoy. I’m also able to follow up on issues, sometimes the very next day. I can react instantly to something happening in the news rather than have to wait for a publication’s approval. I’m also able to interact more with my readers, sometimes responding to their comments."

With a storied career in multiple areas, including writing Mycroft Holmes books, which he said he enjoyed as a challenge to be even more clever in his writing, to acting credits like the fight scene between him and Bruce Lee in Game of Death, Abdul-Jabbar has lived the life of a thousand narratives.

Black Cop's Kid is available here for free to read or listen to for Prime members and Kindle Unlimited subscribers.