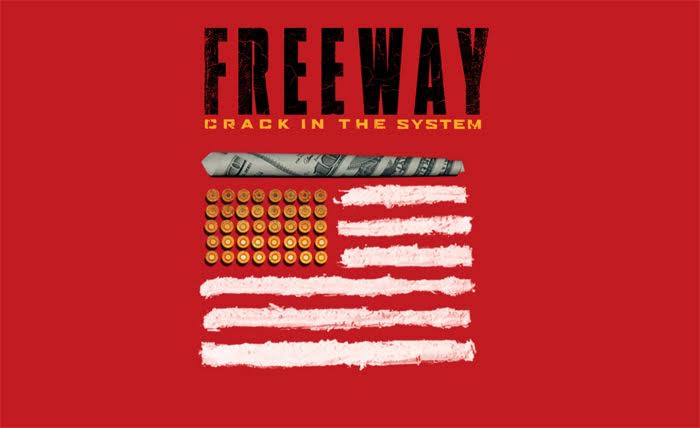

It is a rare instance where art and life truly run parallel, our recently Emmy nominated film “Freeway: Crack in the System” that was presented by Al Jazeera was one of those moments. A tale bigger than life of drug kingpins, government scandal and devastation of the black community, was one that was personal to me as a filmmaker and African American. As one of the producers I looked to my life and its arch as a guide in helping frame the story’s narrative. I grew up in a city of Los Angeles that had been ravaged by gangs, riots and none other than crack cocaine. So when the “Dark Alliance” story written by Gary Webb was published in 1996 implicating that this all might have come with some level of government involvement, put simply it was unbelievable. At age 16 I still remember the hearings in South Central Los Angeles, and the pamphlets passed around by local activist groups telling the community what had happened. Yet, I still did not know that at some point I would have a chance to play a part in making the documentary that would tell the definitive version of how it all went down. A through line that takes us from my hometown of Los Angeles, California, out of the country to Managua, Nicaragua, and all the way to the top of the political ladder in Washington, D.C.

This is the ground covered in our film Freeway: Crack In the System, which is now nominated for an Emmy in the category of Outstanding Investigative Journalism, Long Form. Our goal was to dig deeper with research, and also get exclusive interviews that had never been on camera before, allowing us to have this story laid out in its truest form. From a set of exclusive interviews that included, but were not limited to, Coral Baca the woman that gave Gary Webb his source material to write the Dark Alliance, Julio Zavala the Nicaraguan at the center of the Frogman Case that led to Senator John Kerry challenging President Reagan a full decade before Webb’s Dark Alliance series, and former Sheriff Robert Juarez, who finally was willing to go on camera and admit to the wrongful practices used by he and his partners during the crack era after serving prison time for his illegal actions. All while also weaving this material inside a narrative of the larger than life figure Rick Ross, a man whose life tells so much of the tragedy of the black American experience. As quoted by the Los Angeles times quite literally none other than the infamous “Freeway” Rick Ross sat at the center of the political storm of crack cocaine. Jesse Katz who is also in our film had this to say about Ross in 1996 in the Los Angeles Times:

If there was an eye to the storm, if there was a criminal mastermind behind crack’s decade-long reign, if there was one outlaw capitalist most responsible for flooding Los Angeles’ streets with mass-marketed cocaine, his name was Freeway Rick. He didn’t make the drug and he didn’t smuggle it across the border, but Ricky Donnell Ross did more than anyone else to democratize it, boosting volume, slashing prices and spreading disease on a scale never before conceived. He was a favorite son of the Colombian cartels, South-Central’s first millionaire crack lord, an illiterate high school dropout whose single-minded obsession was to become the biggest dope dealer in history.

Singularly Ross did not serve as the mastermind of crack cocaine in the United States, but he undeniably played his part in its rise. Esquire magazine recently wrote a piece on Ross in it they stated, “Between 1982 and 1989, federal prosecutors estimated, Ross bought and resold several metric tons of cocaine. In 1980 Ross’ gross earnings were said to be in excess of $900 million – with a profit of nearly $300 million. Converted roughly to present-day dollars: 2.5 billion gross, and $850 million in profit, respectively.” The great tragedy is the cost that the Iran-Contra Scandal, and crack sentencing laws created for a post civil rights black America. In addition to this the cultural swelling of drug lore, hip-hop’s fascination with crack stories and the branding of Rick Ross as an antihero only exaggerated those effects. As quoted by Jay-Z ““Can’t you tell that I came from the dope game? — Blame Reagan for making me into a monster — Blame Oliver North and Iran-Contra — I ran contraband that they sponsored” — Jay-Z “Blue Magic” At some point I have to say there is more than enough blame to go around for everyone to finally take responsibility for this disaster and its fallout.

Our job was composing this source material into a storyline which explained the cracks in the system of mass incarceration in America. In effect giving context to why our country now has more African American men incarcerated alone, than nine countries with a combined 2 billion people. Our film attempted to tackle this and so many other issues. As we look at the nomination that recognizes our work in taking on this daunting task, it is a privilege just to be nominated. To be recognized among the diversity of talent the Emmy’s had with the Television Academy nominating 21 actors of color in its total 16 acting categories in the Prime-time Emmys as a black filmmaker is an honor. The recognition of diversity had one site go as far as to use the hashtag #emmysoblack in describing the nomination of our film and other moves of diversity by the News and Documentary Emmys. Despite this, as pointed out in the recent piece in Variety “Artisans So White: Minority Workers and the Fight Against Below-the-Line Bias” there is still work to be done by all of us. May we move ever forward in telling stories like “Freeway: Crack in the System”.

Antonio Moore, an attorney based in Los Angeles, is one of the producers of the Emmy-nominated documentary Freeway: Crack in the System. He has contributed pieces to the Grio, Huffington Post, and Inequality.org on the topics of race, mass incarceration and economics. Follow him on Twitter @tonetalks