For all of the wonderful celebrations that happen during Black History Month, the 28 days also serve as a reminder of how much history has been lost — how much black Americans don’t know about their origins, how many contributions have been covered up, how many unsung heroes lie in unmarked graves.

Thanks to technology, we’re starting to learn more about lost narratives and forgotten people — DNA tests trace ancestry, community-sourced websites gather information and people like Emily Kutil actively work to exhume the buried.

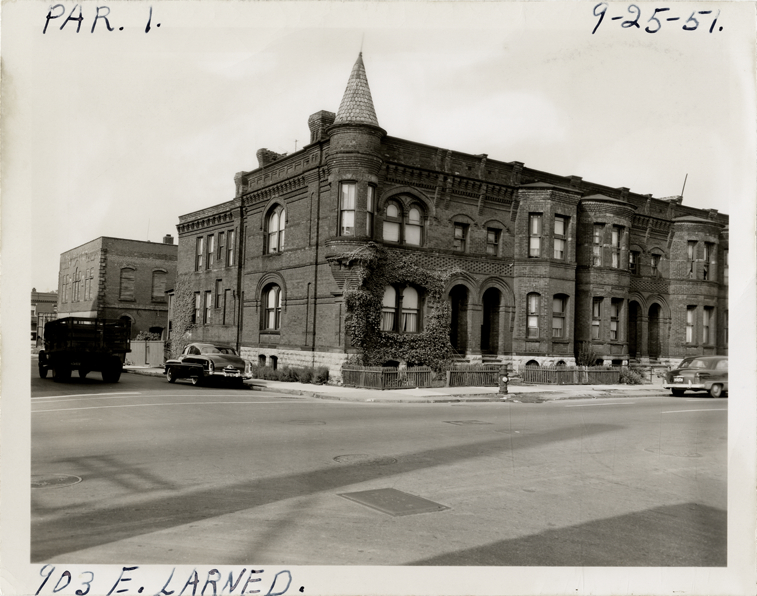

A citizen of Detroit, Kutil has a plan to recreate the Motor City’s long-demolished black mini-metropolis, once called the Black Bottom, online according to the Detroit Free Press.

An architect and historian, Kutil discovered a cache of 800 photographs taken of the Black Bottom in the 1949 and 1950 archived in the Detroit Public Library’s Burton Historical Collection while doing research about Detroit’s Hastings Street.

The pictures were commissioned by the city government; officials wanted to use eminent domain to seize all of the land in the area for a massive redevelopment scheme. First, however, all existing properties had to be appraised so that their owners could be properly compensated.

Detroit’s black population was small at the turn of the 20th century. In 1910, the city had only 6,000 black citizens — 1.2 percent of the metropolis’ total population. Many of these blacks lived alongside immigrants; at the time, the Black Bottom was composed primarily of Syrian, Italian, German and Jewish expatriates.

In the 1920s and 30s, the international feel of the Black Bottom began to change as the Great Migration came into full swing and the color line began to darken. Detroit’s first black mayor, Coleman Young, grew up during that time, and reflected that in the 20s an “adversarial attitude was gathering ominously around the city as the new immigrant groups staked their competing claims for social status, housing and jobs.”

Photo: Detroit Public Library Burton Collection

The same fetid cocktail of racial covenants, blockbusting and redlining that kept blacks restricted to certain parts of town in other cities came to Detroit as well, fencing Detroit’s blacks into the Black Bottom whether they liked it or not.

This led to a cosmopolitan atmosphere that Mayor Young later praised; with black people of all classes, ideologies, and backgrounds living, working, and shopping together “a thrilling convergence of people, a wonderfully versatile and self-contained society” developed.

Alas, the black utopia was not to last.

After World War II, city officials decided that it was time to bring urban renewal to Detroit. They developed the creatively named Detroit Plan, which called for new expressways, communities and hospitals as well as an expanded riverfront and an enlarged campus for Wayne State University.

Mayor Albert Cobo, whose mandate stemmed in large part from white neighborhood associations who wanted to keep their communities white at all costs, decided that the Black Bottom had to go. In its place would be the Chrysler Freeway and the Lafayette Park residential development, designed by Mr. Bland-Black-Box himself, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

The Michigan Chronicle called the plan a “Jim Crow project.” Others said it was nothing short of naked “negro removal.” But despite protests and the fact that evicted blacks literally had nowhere else to go, the city went ahead with the project, leaving the Black Bottom only a memory.

Photo: Detroit Public Library Burton Collection

At least until Detroit Public Library officials Mark Bowden and Romie Minor came across troves of Black Bottom photographs sitting forgotten in storage. When they realized what they were looking at, “We knew we had gold,” Bowden said.

Kutil plans to take all 800 photgraphs the pair discovered and use them to create a digital Black Bottom that users can explore online in the same way you can wander around any city’s streets using Google Street View.

Photo: Detroit Public Library Burton Collection

She has gotten a $15,000 matching grant from the Knight Foundation’s Knight Arts Challenge, but needs to raise $15,000 in order to get the money. If you’d like to help her bring the Black Bottom back to life, you can find out how to do so on the Black Bottom Street View website.