If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

Opinions are the writer’s own and not those of Blavity's.

____

When one of my brothers and I go to a movie theater, we always skip at least one seat between us. When we get a table at a restaurant, we naturally sit diagonally from each other – on opposite sides and on opposite corners of the table. It’s not something that we verbalize or acknowledge, but more of an innate pattern we've adopted at some point in our childhoods so that we don’t look weird or feel awkward.

On the other hand, if I see a movie with one of my sisters, they’re all up on me — squeezing my arm for emotional support every time something intense happens. When we get a table at a restaurant, my sister is practically sitting in my lap and literally eating off my plate.

Those moments of vulnerability and intimacy aren’t shared between my brothers and me. We don't show each other affection, although we know we love each other and have each other’s backs. The difference is: we never really express it. We’ve learned to keep our relationship and our interactions easy, and stoic; masculine and always hetero.

My brothers and I are a lot like our father, who is like his father. Being like my father impacted my life positively in many ways, but inheriting my father’s reluctance to show vulnerability — that part of me became limiting.

Reflecting on my music career, I remember how excited I was to sign my first songwriting deal with a major publishing company, but also how daunting it was to be hired to write love songs because I was still discovering my sexuality and learning how to navigate the fact that I’m gay.

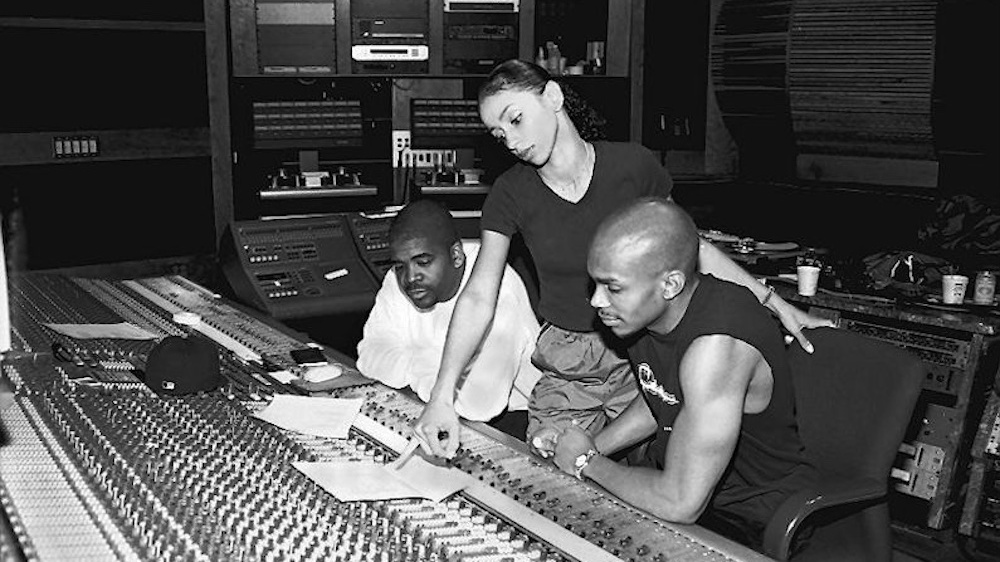

When I write love songs, I'm writing from the revolutionary perspective of a Black man loving another Black man. At the time, I didn't feel the world was ready to embrace that kind of love, so my career became writing songs for powerful women, such as Jennifer Lopez, Brandy, Mya, Jhené Aiko and Deborah Cox, who could perform my songs in a way the world was accepting of and accustomed to.

Being in this Black male body, I was aware of the constructs that it entailed. I thought I had to act a certain way to be successful or considered good enough. I was under the impression that if I was going to be taken seriously in the entertainment industry, I needed to come off as strong and invincible. I had succumbed to the view of Black masculinity that is the product of a long history of racism and oppression. It seemed America only embraced a view of Black men as aggressive, hyper-sexual, misogynistic and homophobic — certainly not vulnerable. At the time, the only places that it seemed safe for Black men to show emotion or any type of vulnerability were either in sports or in church.

I had never really witnessed a Black man that was powerful, respected and accomplished, yet vulnerable and tender; not until I had the opportunity to create with Michael Jackson. Through the absolute perfect alignment of the planets, I wrote a song called “Heaven Can Wait” that Michael wanted to record. That song also moved him to want to meet me, because while listening to the lyrics of the song with his team he said, “I feel like he understands me.”

Being around Michael Jackson was a master class of vulnerability. He always seemed to put the way people felt above everything else, so feelings were always addressed and expressed around him. This made the creative environment productive, rewarding and “magical,” as Michael would say. I now realize that the feeling of collaboration and intimacy that music creation requires is also a necessary resource in photography — a hobby that would ultimately become my career.

Navigating the music industry, I always believed I had to separate what I felt in my heart from what I presented to the world. I assumed they were siloed. This notion was dismantled when I took a trip to South America and began photographing men that were much more emotive and secure with their sexualities than Black American men, and those images became the catalysts that launched my career shift.

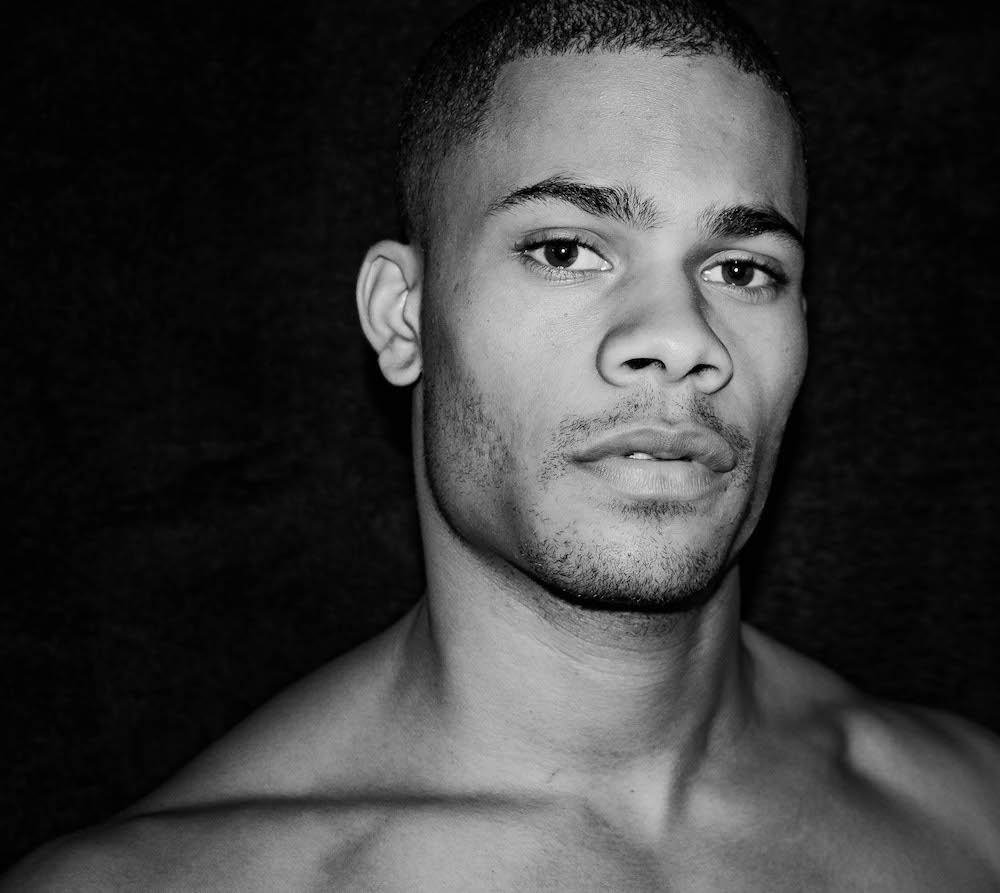

This development prompted me to start working with my subjects in a way that would inspire vulnerability from them. This wasn’t necessarily a simple feat, as many of my subjects are NFL and NBA players, rappers, boxers, executives — powerful Black men that the world often deems emotionally unavailable. I learned to offer a part of myself in exchange for asking for something personal from them. In that space when they discover common aspects of our experiences, that’s when a knowing happens in their eyes where I’m able to capture that moment where they feel seen. They seem both inviting and real; relatable and surprisingly vulnerable.

These men and the resulting photographs have helped me in my reframing of what I consider masculine and beautiful. The idea of expanding the construct of Black masculinity isn’t new. For me, it’s about extending the conversation through my work and intention, and annexing my sensibility to the possibilities of how Black men are seen.

There is an unequivocal bond that exists between Black men; an ineffable cognizance of solidarity and brotherhood. What I’ve discovered in photographing Black men as it relates to intimacy and progress is, if you ask them about their feelings in a way in which they feel safe and free of judgment, and if you *really listen, they will tell you how they feel. And it is my passionate aspiration and intention that when you gaze upon my photographs, you will see how they feel.

I view my photography as an extension of this conversation. If any of the work that I do contributes to the expansion of empathy relating to Black men, masculinity and the non-sexual intimacy we crave and require, that’s the holy grail.

My photography is a reconciliation. It has exposed and liberated me. It requires me to embrace and express feelings of joy and darkness in pursuit of strength and beauty. I now present my photographs the same way I present my music: soulful loves songs about Black men, by a Black man.

____

Teron Beal is a professional photographer and accomplished singer/songwriter.