If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

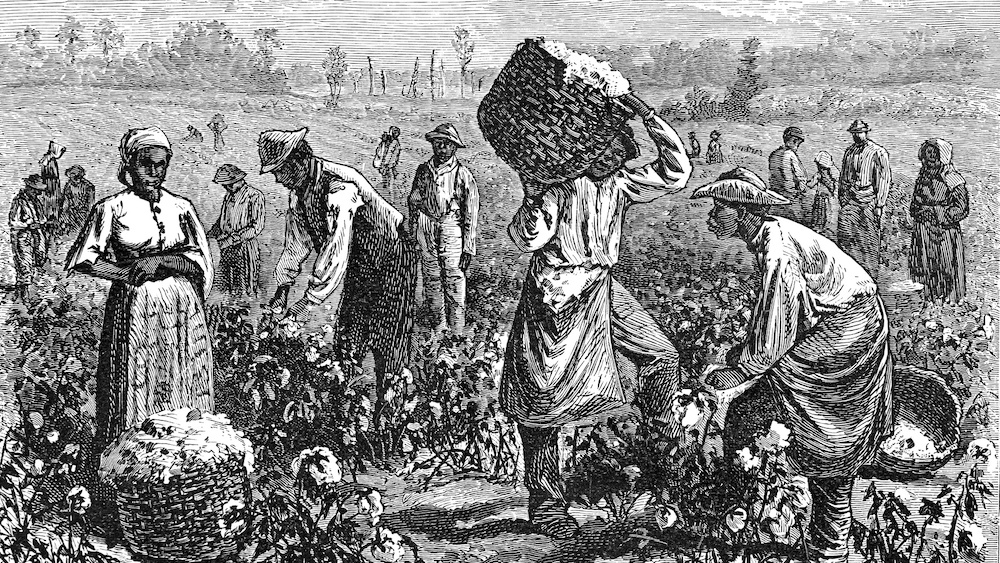

I watched in horror as not just one, but two speakers at the Biden-Harris inauguration referred to the millions of African Americans who were enslaved as “slaves.” The word “slave” is the language of slavery — not democracy. The “peculiar institution” of slavery is our nation’s original sin against African Americans. It cast a shadow so long that we have still yet to reevaluate how it has shaped our vocabulary.

Although we have jettisoned words like “colored,” and more offensive words that I shall not name that refer to African Americans, “slave” still lingers. It is high time to eliminate “slaves” from our lexicon and reassess other language. Rather than “owning” enslaved people, it is more appropriate to say “enslaved” or “held captive.”

Only African Americans can trace their genealogy to American enslaved people. For those of us who are fortunate enough to find a name or a photograph of one of our ancestors, the meaning of American slavery drives a dagger through our hearts ever the more deeply. When I first looked at the single photograph of my great-, great-, great-grandfather, London Walthall, more than 10 years ago, I remember being overcome with emotion.

I looked into Grandpa London’s eyes from a black-and-white newspaper clipping. My heart sank and eyes watered. Grandpa London was born into slavery in 1858 in Virginia. I thought about what it must have been like to live in an insane world that created laws, social customs, religious teachings and science to justify the diminution of people based on their skin color. By the time Grandpa London died in 1964, he had lived a long life alongside his wife Elvira Harvey Walthall. He had seen this progeny grow by leaps and bounds. He had 20 great-great grandchildren mentioned in his obituary. One of those grandchildren was my father.

Over the course of 10 years, I have thought about Grandpa London from time to time when I returned to my genealogical research. Each session renewed my sense of ancestral pride. The striving of African Americans in a country that denied their human and civil rights for much of its history is a marvel of human triumph to be celebrated.

I had not anticipated how the Black Lives Matter Movement would bring me even closer to American enslaved families. The origins behind every horrific headline can be traced to slavery — how combating racism required new vaccines but was never really eradicated. Until this nation restores the personhood of the Black enslaved family, we cannot defeat the perennial battle of racial injustice.

I set out to restore their personhood in my own way beginning in 2020. I had become somewhat of a local historian for the Southwest neighborhood in Washington, DC. I had read about slavery plantations in the 1790s and captors’ connections to the establishment of a local Catholic church. Southwest was a refuge for enslaved families escaping from slavery and for legally free Black people as early as the 1830s. In 1848, it was the scene of a major escape of enslaved people called the Pearl Incident, which eventually led to the ban on the slave trade in Washington, DC.

I invited the community to an event that I called, “Enslaved Families Remembrance and Personhood Restoration Day.” While only two people showed up, it was deeply rewarding for me. Never had I heard about a remembrance for enslaved families — or since. We read the names of enslaved families that lived in early Southwest from the will of a family who held enslaved people captive. The full version of my speech is on Wikipedia. Below is an excerpt:

We should remember and honor their legacy. We should affirm their contribution, including their labor, when we tell our community’s history, create property listings for real estate, and designate buildings as historic. We should affirm their contribution when we teach our children in the classroom and living room and show our visitors around the neighborhood. This nation should be ashamed of slavery — for which it has still not apologized, but we should not be ashamed of the labor and work of enslaved people.

I had taken a lantern with a battery-powered candle to that event, which I decided to keep lit in my small studio apartment. It informs so much of my daily life. I eat right and exercise in hopes of living as long as Grandpa London. I dedicated even more to my research and teaching as I complete my PhD at the University of Maryland, because Grandpa London was denied an education. I discuss the history of slavery in Southwest when I give tours. I have even used the perspective of enslaved people to analyze health theories.

Just as Grandpa London has taught me so much from the grave, the restoration of enslaved families can teach us so much as a nation. We could be enlightened from their struggle. I believe that it would lead us to a national apology and reconciliation with slavery, establishmet of community-based reparations and a national museum of enslaved people and slavery, even a national holiday. Once we accept that slavery never should have happened in the first place, it becomes much harder to live with all of the racism around us.

____

Chris Williams is a PhD student at the University of Maryland School of Public Health. His research interests include neighborhood change and health, health disparities, political determinants of health and community strengthening. He is editor-in-chief of Southwest Voice and a steering committee member of the DC Grassroots Planning Coalition.