If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

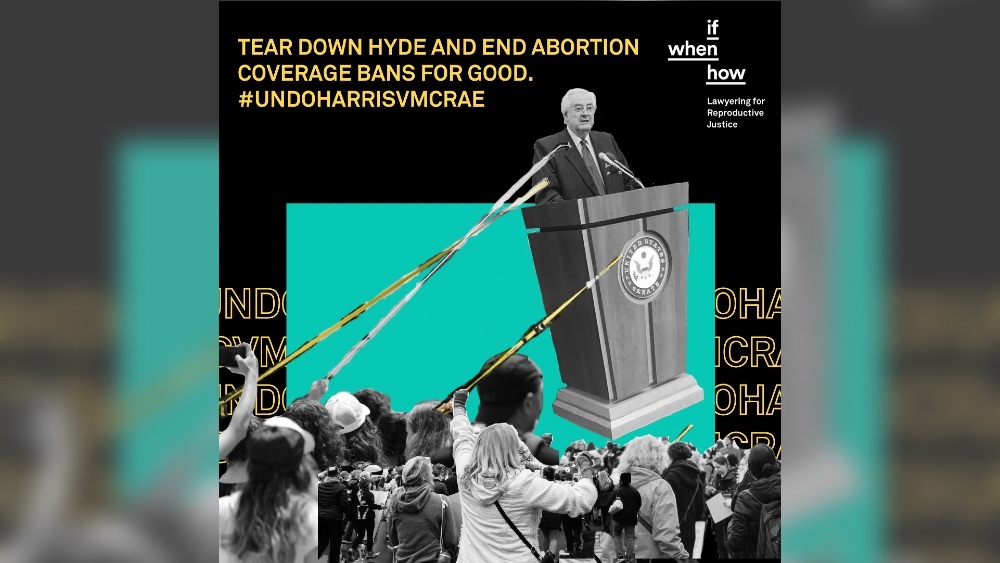

In the last year, we have seen communities pull down actual statues erected to celebrate, honor and perpetuate white supremacy. Now, it’s time to destroy some figurative monuments to white supremacy as well — specifically the bans on insurance coverage for abortion that have prevented one in four low-income people from accessing the care they need, and which disproportionately put care out of reach for Black women and girls, people of color, young people, immigrants, and trans, queer and gender non-conforming folks — not by circumstance, but by design.

Just as confederate statues were erected to preserve and uphold white supremacy, we see systemic paeans to institutional racism in the electoral college, the Senate filibuster and policies like the Hyde Amendment, which blocks Medicaid coverage for nearly all abortion care. On the surface, these may seem neutral, but in reality they serve to systematically discriminate against people of color.

You’ve likely heard of the Hyde Amendment thanks to the organizing work of people of color in the reproductive health, rights and justice movements who have raised awareness about its harm. But you may not have heard of Harris v. McRae, the Supreme Court case that provides the legal underpinnings for Hyde. Until we overturn this case, even repealing Hyde won’t eliminate the looming spectre of future coverage bans that could be reintroduced by anti-abortion politicians who are anxious to deny abortion access to those who already face the most barriers to care.

Indeed, Hyde and the McRae case were steeped in racism, sexism and classism from inception. Congressman Henry Hyde openly said as much in 1976, when he introduced his rider during the annual budget process: “I certainly would like to prevent, if I could legally, anybody having an abortion, a rich woman, a middle-class woman or a poor woman. Unfortunately, the only vehicle available is the … Medicaid bill.”

After the Hyde Amendment was first passed in 1976, Cora McRae, who was directly impacted by the restrictions, and other plaintiffs including a group of New York clinics and hospitals, and the Women’s Division and officers of the Board of Global Ministries of the United Methodist Church, took their case all the way to the Supreme Court, challenging the restrictions on federal funding being used to cover abortion care. In this case, the Supreme Court narrowly ruled to uphold the Hyde Amendment, reasoning that while the government could not place an obstacle in the path of a person exercising their right to abortion, there was no obligation for the government to remove obstacles. The ruling essentially ignored the systemic inequalities — including racism — at the root of economic disparities and poverty, and instead upheld the legal ideology that the government has no obligation to remove barriers, without fully recognizing the ways the government actually had a hand in creating those inequities.

In his McRae dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall named the Hyde Amendment for what it was, writing that “the Hyde Amendment [was] designed to deprive poor and minority women of the constitutional right to choose abortion.” Justice Marshall identified then what we still know to be true today: “the undeniable fact that, for women eligible for Medicaid — poor women — denial of a Medicaid-funded abortion is equivalent to denial of legal abortion altogether.” The Hyde Amendment created a tiered system of abortion access, denying care to people who qualify for public health insurance.

We know that economic justice is reproductive justice is racial justice, and the effects of the Harris v. McRae ruling are still being felt today in a system concerned with a right to abortion that does not exist in practice for millions of people in this country. Fast-forward 40 years, and last summer’s June Medical decision — which challenged abortion restrictions in Louisiana — demonstrated that the status quo is still not enough when it comes to going beyond the right to abortion and ensuring access to care. Chief Justice Roberts’ concurrence is already being used to undermine access by signaling a roadmap to states on ways to enact restrictions that would be deemed constitutional.

Low-income folks, including a disproportionate number of whom are women of color, must not be barred from accessing care by anti-abortion politicians withholding Medicaid coverage for abortion via Hyde and, beneath it all, Harris v. McRae. That’s why If/When/How is working with coalition organizations and movement leaders to raise awareness about the lasting impact of this case, as well as generating the legal arguments and organizing the attorneys who will someday overturn it.

We’re providing technical assistance and support to our movement partners, and we’ve teamed up with reproductive justice organizations like New Voices for Reproductive Justice to use our legal expertise to uplift the lived experiences of the Black women, girls and gender non-conforming people who are most impacted by abortion restrictions. And we’re mobilizing our extensive network of law students and lawyers to both raise awareness about the impact of Harris v. McRae, and to be ready to join the fight in challenging this legal travesty and dismantling its harmful impact so that we can secure coverage for abortion once and for all.

____

Jeryl Hayes is the Movement Building Director at If/When/How: Lawyering for Reproductive Justice.