Jordan Besek, University at Buffalo

____

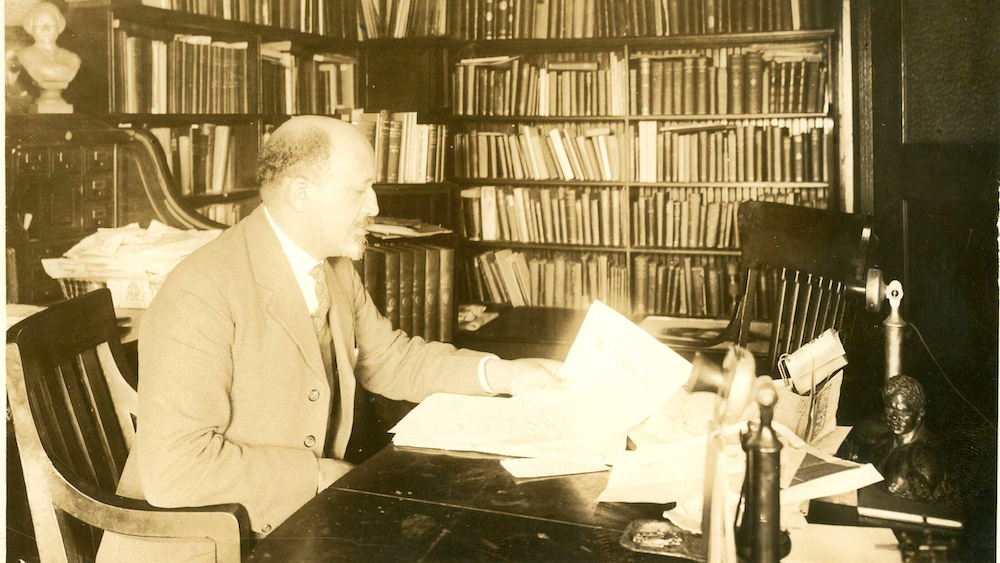

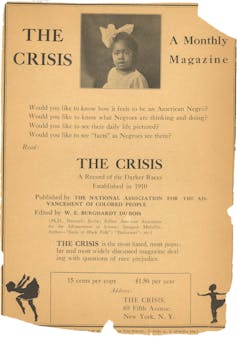

The NAACP – the most prominent interracial civil rights organization in American history – published the first issue of The Crisis, its official magazine, 110 years ago, in 1910. For almost two and a half decades, sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois served as its editor, famously using this platform to dismantle scientific racism.

An advertisement for The Crisis, circa March 1925. W.E.B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, CC BY-ND

At the time, many widely respected intellectuals gave credence to beliefs that empirical evidence exists to justify a “natural” white superiority. Tearing down scientific racism was thus a necessary project for The Crisis. Under Du Bois’ leadership, the magazine laid bare the irrationality of scientific racism.

Less remembered, however, is how it also sought to help its readers understand and engage with contemporary science.

In nearly every issue, the magazine reported on scientific developments, recommended scientific works or featured articles on natural sciences. Du Bois’ time as editor of The Crisis was just as much about critically embracing careful, systematic, empirical science as it was about skewering the popular view that Blacks (and other nonwhites) were naturally inferior.

Sociologists Patrick Greiner and Brett Clark

and I recently pored through the magnificent W.E.B. Du Bois Papers at the Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. We found that Du Bois not only drew from natural sciences, but thought deeply about the ways in which The Crisis should and should not do so. He would even go so far as to critique allies for using science in ways he thought inappropriate.

Case in point: Defending Darwin

On Feb. 18, 1932, the Harlem pastor Adam Clayton Powell wrote to Du Bois, asking him to publish his recent address at a NAACP mass meeting in an upcoming issue of The Crisis.

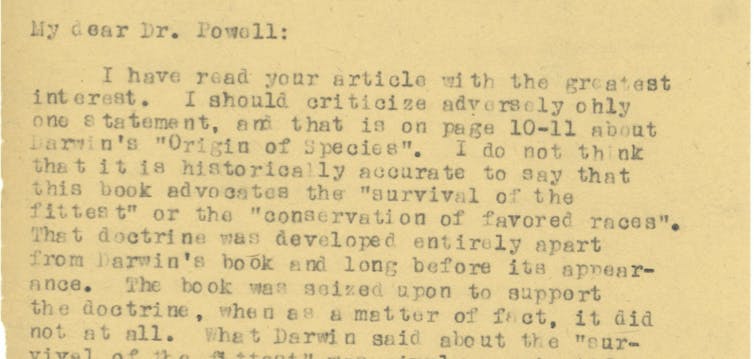

A week later, Du Bois responded that while he’d read Powell’s address “with great interest,” he could not publish it as written. Why? It got biologist Charles Darwin and his theory of natural selection very wrong.

An excerpt of Du Bois’ letter of Feb. 25, 1925 to Adam Clayton Powell. W.E.B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

Darwin, explained Du Bois, did not try to demonstrate “who ought to survive,” as Powell’s address assumed. Rather, Darwin’s work is “simply a scientific statement” that had been twisted to support eugenicist and other pseudo-scientific doctrines.

This short reply to the powerful pastor contains so much. It shows that Du Bois demanded a nuanced appreciation of Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Further, he insisted Darwin should not be held liable for the racist ideologues who misappropriated his work, cloaking their demagoguery in scientific objectivity. Darwin’s work is of clear value, but one must always remain aware that, like with all science, politics shaped its reception.

For Du Bois, how one understands and uses science were not minor issues.

Science in The Crisis

In the first section of the first issue of The Crisis, there is an archaeological report. It describes how “exploration of the African continent is yet in its infancy and will doubtless yield surprising results in establishing the advanced state of development attained by the black races in early times.”

According to the latest archaeology, in other words, African heritage is something to be proud of.

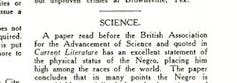

On page 6 of the inaugural issue of The Crisis, a subheading for ‘SCIENCE.’ The Crisis. Vol. 1, No. 1; 1910. The Modernist Journals Project. Brown and Tulsa Universities, ongoing. www.modjourn.org

Later in that issue, under the subheading “Science,” it is noted that a paper was read before the British Association for the Advancement of Science concluding that “all earlier human races were probably colored.” This same section notes a recent study providing evidence that, in a direct rebuke to scientific racism, “mere brain weight is no indication of mentality.”

In the second issue of The Crisis, the famed Columbia University anthropologist Franz Boas explained that there is no physical anthropological evidence “showing inferiority of the Negro race.” Later issues would highlight early African metallurgy and critique racist intelligence tests. Another would recommend a work by Peter Kropotkin, the great Russian anarchist and zoologist, which suggested that natural selection is more about cooperation among species than any fight for survival between them.

The Crisis published articles by prestigious scholars who drew on science to refute racism. The Crisis, Nov. 1932

The Crisis published this sort of work throughout Du Bois’ time as editor. The reason why is clear. Du Bois knew that a proper understanding of science does not lead to biological essentialism – the idea that biology limits who you are and what you can do. It leads to the exact opposite conclusion, that every population has the ability to make their own meaning and determine themselves as they see fit. The only constraints are social processes like colonialism and racism. Science, for Du Bois, was in this way necessary and liberating.

Science for an emancipated politics

Today’s political moment is different than Du Bois’, though there are some parallels. One is that a political life free of exploitation and enhanced by participatory democracy remains out of reach for many. Disenfranchisement still exists in many forms. As the Black Lives Matter movement and others have shown, racism is a big reason why.

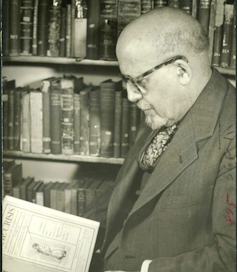

W.E.B. Du Bois in his office, ca. 1948, holding the first issue of The Crisis. W.E.B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, CC BY-ND

While only a piece of the puzzle, Du Bois’ insistence on critically embracing a careful, systematic and empirical view of science can be an important part of that struggle for an emancipated politics. A critical embrace of science can help people better tackle pressing issues like environmental justice, health care disparities and more.

To critically embrace science is to, as Du Bois did in the pages of The Crisis, remain unwavering in the fact that any scientific theory promoting racial and other forms of injustice is categorically wrong.

He demonstrated how to reject racist science without rejecting the ways that science can help people better understand our relationships with the world. In particular, engaging science shows how our relationships with each other are not determined by nature, but are under our own control.

[Deep knowledge, daily.

Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.] ![]()

____

Jordan Besek, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University at Buffalo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.