If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

By 1965, the idea of the “American Dream” had become a valuable branding tool in strengthening the U.S.’s cultural and economic dominance around the world. It was both a convenient and alluring narrative. Proof that the American experiment was working.

But even then, the Dream was buckling under a much grimmer reality — one that no amount of white picket fences could conceal. Images of state violence against peaceful protestors were reverberating across the nation; Martin Luther King Jr.’s jailhouse letters were proliferating far beyond the South; and public intellectuals like James Baldwin were gaining international acclaim for eloquently exposing the contradictory reality of that Dream.

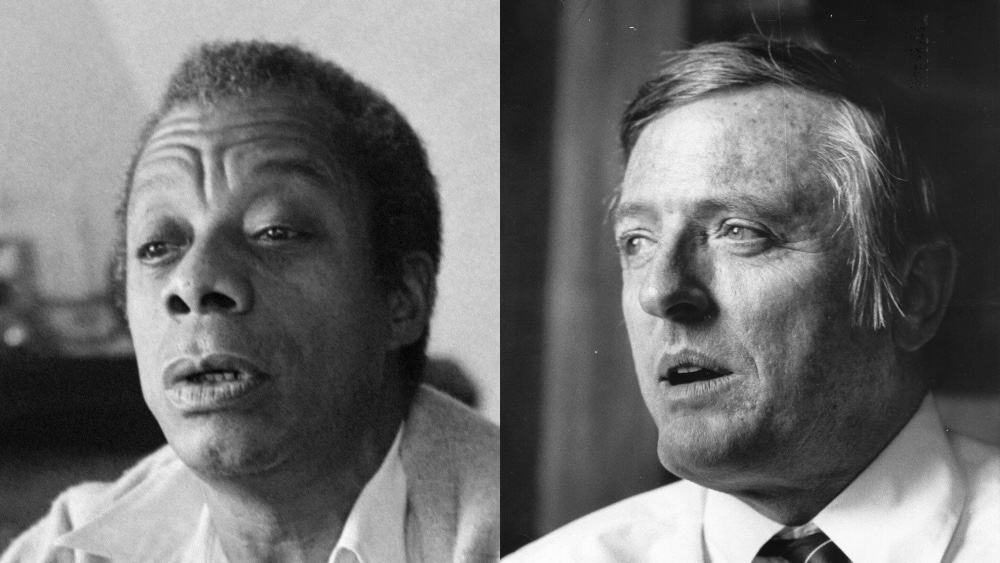

Undergraduates in the United Kingdom — like many around the world — were riveted by this dichotomy. That February, they crammed the floors of the Cambridge Union to hear Baldwin debate the conservative editor of the National Review, William F. Buckley, on the question: “Is the American Dream at the expense of the American negro?”

55 years after that ideological confrontation, the world is once again watching as America’s defining mythology is being challenged by those whose experiences have been more like nightmares. Against the backdrop of continued state violence against Black citizens, an insurrectionary summer and unprecedented income inequality, the March on Washington Film Festival kicked off its 2020 lineup by re-imagining that debate within our current — yet familiar — political context.

Furthering Baldwin’s original position, Dr. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School, argued that any seemingly positive statistics about Black advancement toward an American Dream merely “passes as racial progress” at the expense of the true “complexities of how the nation actually functions.” Dr. Muhammad quoted from a text that described Black America as an internal colony, with “failing schools, underfunded hospitals, toxic water [and] occupying police forces,” all of which are by design. It is reminiscent of what former Ghanaian president and pan-African scholar Kwame Nkrumah wrote in his seminal piece on the imperial pattern: “Neo-colonialism, like colonialism, is an attempt to export the social conflicts of the capitalist countries. The temporary success of this policy can be seen in the ever-widening gap between the richer and the poorer nations of the world.”

David Frum, a conservative writer from The Atlantic whose work has been praised by Buckley, furthered the opposing ideological position. As Buckley did in 1965, Frum gave a much rosier view of the American experiment and its resulting “Dream,” rebuking Baldwin’s depiction as being dangerously full of despair. Despite what he admits might be an “inconsistent” or “hypocritical” execution of America’s founding principle of equality — generous euphemisms for the enslavement of human beings and ongoing socioeconomic devastation — he claimed that “Black Americans are not the Dream’s victims; Black Americans are the Dream’s test.”

Unlike the original debate, MoWFF provided a much more robust opportunity for active student participation in the discussion. David “Tre” Edgerton of the Howard University Debate Team cross-examined Dr. Muhammad, asking what a Black version of the American Dream could look like outside of a Eurocentric agenda. Michael Franklin, also of the Howard University Debate Team, challenged Frum on whether it might be better to recast Baldwin’s “despair” as realism. It would be appropriate, Franklin argued, given that America has so often failed the “test.”

Actress Yara Shahidi, of shows like Black-ish and Grown-ish, and a big fan of Baldwin’s work, closed the event by acknowledging the importance not only of Baldwin’s artistry, but the way he chose to wield it, and the lasting impact it’s had on the movement. As W.E.B. DuBois once wrote in his essay, “Criteria of Negro Art,” “…all Art [sic] is propaganda and ever must be…I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of Black [sic] folk to love and enjoy.”

Just as the students did at Cambridge in 1965, viewers in the livestream chat box seemed to agree that the American Dream has indeed come at the expense of Black Americans. But the question remains: Where do we go from here?

____

Jada F. Smith is a former program manager for the March on Washington Film Festival and a writer working to find new and old ways of building and strengthening community. A graduate of Howard University living in Houston, TX, her work has appeared in The New York Times, The PBS NewsHour, ZORA, Lenny Letter, Mic, The Root, Texas Gardener Magazine, Nosh Culinary Magazine and more.