This piece was submitted from a member of our enthusiastic community of readers. If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

September 2018, after Kanye West received an old-fashioned tongue-lashing on public radio and an outpouring of community spiritual uplift, making appearances in his hometown, Kanye West declared he's moving back to Chicago. October 2018, Kanye took this energy to Uganda, where he sat amongst young children and elders, bearing gifts and receiving rituals of healing and community. In essence, when he returned home to Calabasas, California, he recreated these experiences in the form of Sunday services — bringing the healing pulse of Chicago and Uganda to him. In 2019, Kanye West plans to bring this experience to every home by way of his newest album, Jesus is King.

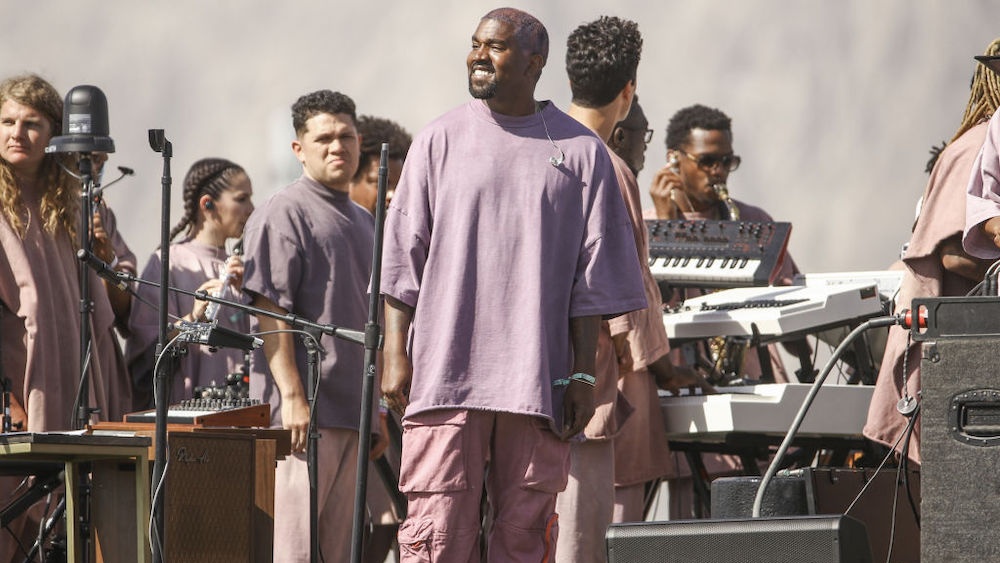

Kanye began having almost-weekly “Sunday services” in Calabasas, California, in January 2019 as a private sanctuary for family, friends and a host of musicians and artists he admires. As Calabasas has been said to mean, “where the wild geese fly,” after a whirlwind year of erratic behaviors and impulsive speech, Kanye’s flight to “making music on the hill” was timely and perhaps symbolic. Kanye turned Calabasas, a known site for the white rich and famous, into a small, largely Black collective gathering with an aesthetic of the age-old African “healing circle.”

Healing from what, for Kanye? I imagine his travels made him aware of the injury of speaking “slavery is a choice,” aligning with the occupant of the White House and the deeply felt ways Kanye has too often devalued and dismissed Black women’s concerns for his treatment in representation and everyday life. In addition, he suffered the duress of mental health issues, which potentially heightened these episodes of public misfitting. Kanye needed work; he needed community and he sought redemption.

Sunday services in Calabasas were what the doctor ordered: a return to Chicago sonic heaven and healing, within the private confines of his home, away from spectacle-hungry public.

As a Chicago Southsider who sang in some of the premier gospel choirs of the '90s, the choir in Calabasas was like a childhood memory — where making music allowed folks a space to build community and reflect on something greater than the self, far away from the realities of our complex, Black lives. Instruments were at the center — from keyboards to drums — while the choir and guests gathered in song and elation, humming and belting classic Chicago gospel anthems. As the choir moved into songs such as “Jesus Walks” and “Ultralight Beam,” playing with melody, rhythm, cadence and voice, the connections between Chicago gospel and Kanye production were clear. Compared to concert performances, which frequently place Kanye at center stage, the common absence of his body from the frame of the livestream allows us to focus on the community built. This was a healing circle for Kanye, but it felt like church to so many of us.

Yet, the Sunday service in Calabasas was far away from the churches we had come to know in our youth (and adulthood), which housed the contradictory presence of holiness and hell-raising. Everyone was welcomed at Calabasas; notably present, were those for whom the church commonly denied access. Kanye’s Sunday service was something ethereal, otherworldly — an escape into the wild on a land of plenty.

Kanye’s hilltop performances of gospels and hymns, outside of the traditional church structure, allowed for a disregard of Black church etiquette, creating space for all types of freedoms. Children danced and sang around the circle, flying through the space and often grabbing the microphone, with no finger-wagging or stares. Choir members moved from gospel two-steps to the milly rock, without any looks of disapproval or questions of “time and place.” Here, we see the wildness of Kanye's musical sensibility and thought rub intimately against the winds of inspiration and individual experiences.

In the hills of Calabasas, there were little constraints; creativity was the order of the hour, and Kanye and friends were master chefs. Those of us who were religiously attuned to Sunday service were witnesses to a clear break away from the church — the felt absence of the echoes of hierarchy, licensed misogynoir and misogyny, homophobia and femmephobia, sex-negative culture and the tendency to tame. Indeed, these are ingredients ripe for making a better man. The Sunday service was an unapologetic merger of raw, uncensored hip-hop and the holy, sacred, gospel, made available to all people.

Enter the church.

On September 15, 2019 Kanye stood in the large sanctuary of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church — one of Atlanta, Georgia's Black megastructures — near silent, absorbing the rays of sonic celebration. As the choir commands “there is nothing too hard for God,” contemplative Kanye signals a decrescendo and begins to engage in testimonial. He speaks: “You sent your son to die for us and all you ask is for radical obedience to you." While what he states here and everything beyond it is common Black speech in front of church congregations around the world, Kanye addressing this audience with this line (along with his elongated pause) communicated a sort of transformation.

Although I am unclear as to how “radical obedience” will activate in Kanye’s creative work or in his life, I cringe at the choice of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church as the site of “healing work.” This church is now home to Reverend Jamal Bryant and previously the late Bishop Eddie Long — both whose widely-known abusive practices have been met with little remorse and no acts of restoration. Of course, the church as an institution is marred by its numerous, unaddressed violences. As if drawing from the school of Jay-Z, Kanye’s partnership with the church ignores an important fact: the church (and its leaders) have yet to re-earn the people’s trust.

While Kanye may not have known this church venue or its past, the history of this church (and the larger church) as spaces largely unapologetic for its injuries to the public in the name of Jesus makes inhospitable to the collective community so-present and precious in the choir of Calabasas. With Kanye having his own injuries to atone for, the church — and particularly this church — should have been the last place of collaboration.

The church cannot contain the wildness of Mr. West, neither can it render the salvation he needs. While I imagine the Jesus is King album will possess the wild, sonic and often secular Kanye-esque moves, I do not think this “move to gospel” necessitates a relationship to the church and its all too common ailments.

Kanye, go back to Calabasas!

I am afraid in your search for redemption, you have moved from being pimped by the president to being a pawn for the church.

Neither is your home.

____

Jeffrey Q. McCune Jr. teaches African & African American Studies and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. He is an award-winning author, who is completing a book on Kanye, a critical engagement with black genius, iconography, and monster aesthetics. McCune has been featured on Left of Black, Sirius XM's Joe Madison Show, HuffPost Live, Pitchfork, the Christian Monitor and a guest expert on Bill Nye Saves The World.