If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

Opinions are the writer’s own and not those of Blavity's.

____

Recently, I sat in on a lesson in which the third graders at P.S. 78 in Staten Island were learning something too many of us never learn as adults: how to handle difficult emotions. The children spun a wheel that stopped on a challenging situation and each child chose a method of coping.

The wheel landed on a math question that was hard to figure out. What do you do? One girl said she would take long, slow, deep breaths until she was calmer. Another student said he would take a walk and tackle the problem later. Yet another decided he would play music as he did the problem.

Through a proven educational approach called social-emotional learning used in schools nationwide — implemented in NYC two years ago — these students are discovering that they have the power to resolve tough feelings in a healthy way, build relationships and resolve conflicts. These skills will serve them well their entire lives.

For most children, and especially children of color like the ones at P.S. 78, this important early investment in emotional and mental well-being is a radical departure from the ways of the past. This July, BIPOC Mental Health Month comes as the pandemic and George Floyd’s murder have placed a bright spotlight on structural racism and inequities in many sectors, and mental health is no exception. That’s why the CDC recently declared that racism is a public health crisis. For our children, it is a particularly urgent one.

As of 2018, suicide became the second leading cause of death in Black children aged 10 to 14, and Black children under 12 kill themselves at twice the rate of white children. Studies suggest that Latina adolescents attempt suicide at higher rates than Black or white adolescents.

Overall, the American Counseling Association reports that individuals from BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) communities receive mental health treatment at far lower rates than the U.S. average of 43%. For Latinx adults the percentage is 33%; it is 30% for African Americans and 28% for Asian-Americans.

When care is sought, BIPOC communities face many roadblocks: poorer quality of care, racism and bias in treatment settings, less access to treatment. Too often, these problems mean a diagnosis that is incorrect, missed or dropping out of care.

We know that culturally responsive mental health treatment and support can save lives and positively change the trajectory of families and whole communities. But the majority of mental health providers in the United States are white. For example, approximately 86% of psychologists are white and less than 2% of American Psychological Association members are African American.

As a mental health advocate of color, I insist that if we are serious about addressing historic injustices, mental health services must be integrated into primary healthcare and all areas of life, especially education and employment. In any given year, 1 out of 5 people experience a mental health challenge. Everyone has a family member or knows someone who is affected.

Right now, we have a once-in-a-generation moment to grow an infrastructure of care, as more resources to address inequity flow from federal and local governments.

For starters, we can increase the number of certified community behavioral health clinics or centers (CCBHC) across the country. These centers, which address mental health and substance misuse problems, rely on innovative partnerships with the communities they serve by working with those in education, social services and criminal justice. Last year, Congress expanded what started out as an eight-state Medicaid demonstration program for these clinics and has funded them since 2018. About 340 CCHBCs are in 40 states, Washington, D.C. and Guam.

Across the country, some of the best places to spend our dollars are with BIPOC-led community-based organizations. Over five years, New York City’s Connections to Care program proved that community-based social service providers can be equipped to recognize and address clients’ mental health needs and connect those with serious needs to additional clinical treatment.

Our diverse group of CBO partners know the needs of BIPOC communities they have served for decades. This year, we are bringing this model of community-based mental health integration to workforce development programs for public housing residents.

Connections to Care exemplifies a principle that is especially important in the context of historic inequity: do not wait for people to come to you, meet people where they are. That is why NYC now has mental health amplifiers checking in on people at vaccine sites and connecting them to mental health resources.

We have also learned the importance of integrated care. After all, there is no health without mental health. Our COVID Centers of Excellence — all in BIPOC neighborhoods — provide comprehensive short and long-term care for recovering COVID-19 patients and services for community residents. These communities were among those identified by our Taskforce on Racial Inclusion & Equity as hardest hit by the pandemic. The second of three planned centers recently opened in Queens, bringing together mental health care with dental and vision care, diabetes management, pediatric care and more.

As our country works toward a pandemic recovery, we must put BIPOC mental health front and center with investments in education, health and BIPOC-led CBOs. There is a role for all of us — individuals, government, businesses and philanthropies to help make mental well-being a human right for all.

____

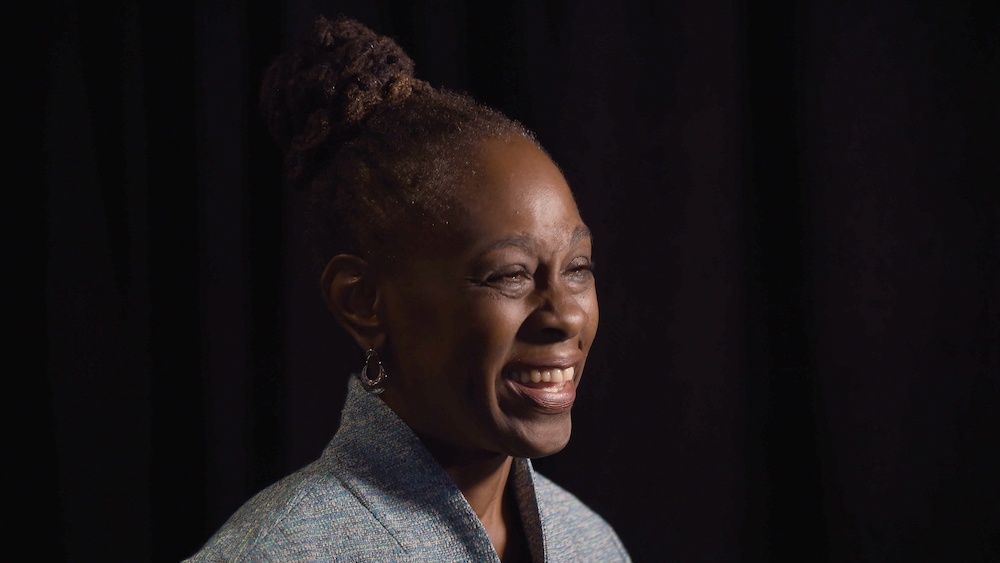

Chirlane McCray is the First Lady of New York City, a mental health advocate, and a co-chair of the city’s Taskforce on Racial Inclusion and Equity.